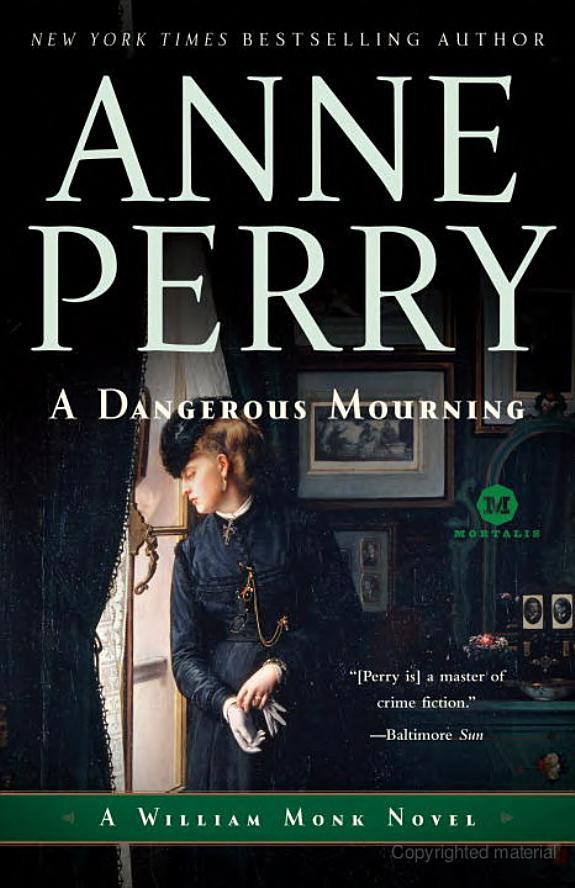

![William Monk 02 - A Dangerous Mourning]()

William Monk 02 - A Dangerous Mourning

smile.

“Thank you, I shall manage by myself,” Romola snapped. “And I intend to go and visit Lady Killin tomorrow afternoon.”

“It is too soon,” Basil said before Cyprian could speak. “Ithink you should remain at home for another month at least. By all means receive her if she calls here.”

“She won’t call,” Romola said angrily. “She will certainly feel uncomfortable and uncertain what to say—and one can hardly blame her for that.”

“That is not material.” Basil had already dismissed the matter.

“Then I shall call on her,” Romola repeated, watching her father-in-law, not her husband.

Cyprian turned to speak to her, remonstrate with her, but again Basil overrode him.

“You are tired,” he said coldly. “You had better retire to your room—and spend a quiet day tomorrow.” There was no mistaking that it was an order. Romola stood as if undecided for a moment, but there was never any doubt in the issue. She would do as she was told, both tonight and tomorrow. Cyprian and his opinions were irrelevant.

Hester was acutely embarrassed, not for Romola, who had behaved childishly and deserved to be reproved, but for Cyprian, who had been disregarded totally. She turned to Basil.

“If you will excuse me, sir, I will retire also. Mrs. Moidore made the suggestion that I should be in my room, in case Lady Moidore should need me.” And with a brief nod at Cyprian, hardly meeting his eyes so she did not see his humiliation, and clutching her book, Hester went out across the hall and up the stairs.

Sunday was quite unlike any other day in the Moidore house, as indeed was the case the length and breadth of England. The ordinary duties of cleaning grates and lighting and stoking fires had to be done, and of course breakfast was served. Prayers were briefer than usual because all those who could would be going to church at least once in the day.

Beatrice chose not to be well enough, and no one argued with her, but she insisted that Hester should ride with the family and attend services. It was preferable to her going in the evening with the upper servants, when Beatrice might well need her.

Luncheon was a very sober affair with little conversation, according to Dinah’s report, and the afternoon was spent in letter writing, or in Basil’s case, he put on his smoking jacketand retired to the smoking room to think or perhaps to doze. Books and newspapers were forbidden as unfitting the sabbath, and the children were not allowed to play with their toys or to read, except Scripture, or to indulge in any games. Even musical practice was deemed inappropriate.

Supper was to be cold, to permit Mrs. Boden and the other upper servants to attend church. Afterwards the evening would be occupied by Bible reading, presided over by Sir Basil. It was a day in which no one seemed to find pleasure.

It brought childhood flooding back to Hester, although her father at his most pompous had never been so unrelievedly joyless. Since leaving home for the Crimea, although it was not so very long ago, she had forgotten how rigorously such rules were enforced. War did not allow such indulgences, and caring for the sick did not stop even for the darkness of night, let alone a set day of the week.

Hester spent the afternoon in the study writing letters. She would have been permitted to use the ladies’ maids’ sitting room, had she wished, but Beatrice did not need her, having decided to sleep, and it would be easier to write away from Mary’s and Gladys’s chatter.

She had written to Charles and Imogen, and to several of her friends from Crimean days, when Cyprian came in. He did not seem surprised to see her, and apologized only perfunctorily for the intrusion.

“You have a large family, Miss Latterly?” he said, noticing the pile of letters.

“Oh no, only a brother,” she said. “The rest are to friends with whom I nursed during the war.”

“You formed such friendships?” he asked curiously, interest quickening in his face. “Do you not find it difficult to settle back into life in England after such violent and disturbing experiences?”

She smiled, in mockery at herself rather than at him.

“Yes I do,” she admitted candidly. “One had so much more responsibility; there was little time for artifice or standing upon ceremony. It was a time of so many things: terror, exhaustion, freedom, friendship that crossed all the normal barriers, honesty such as one cannot normally

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher