![William Monk 18 - A Sunless Sea]()

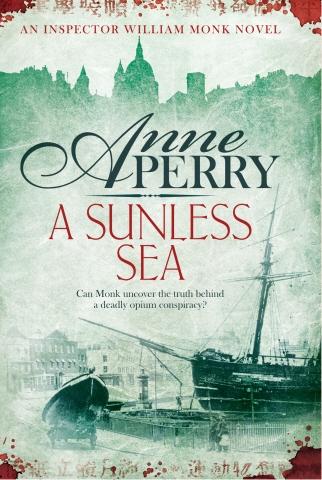

William Monk 18 - A Sunless Sea

WOMAN HORRIBLY MURDERED ON LIMEHOUSE PIER , read one headline. WOMAN GUTTED AND LEFT TO DIE LIKE AN ANIMAL , said another.

He had them folded, headlines concealed under his arm, when he reached his own kitchen door. He smelled bacon and toast, and heard the kettle whistling on the hob.

Hester was standing with the toasting fork in her hand, taking the fresh piece off and putting it into the rack with the others, so it would stay crisp. She closed the oven door and smiled at him. She was dressed in her favorite deep blue. For a moment, looking at her, Monk could put off a little longer the thoughts of violence and loss, the chill on the constantly moving water and the smell of death.

Perhaps he should have told her last night about the woman, but he had been tired and cold, and aching to put the horror of it out of his mind. He had needed to get warm and dry, to lie close to her and hear her talk about something else—anything at all that had to do with sanity and the small, healing details of life.

She was looking at him now and reading in his face that something was badly wrong. She knew him far too well for him to dissemble—not that he ever had. She had been an army nurse in the Crimean War, a dozen years ago, before they had met. There were few horrors or griefs he could tell her that she did not already know at least as well as he.

“What is it?” she asked quietly, perhaps hoping that he could tell her before twelve-year-old Scuff came down for his breakfast, eager for the new day, and everything he could eat. About a year ago they and Scuff had mutually adopted each other, Hester and Monk because Scuff was homeless, living precariously on the river, mostly by his wits. It was not that he was an orphan, but that his mother had too many younger children to have time for him, or maybe his mother’s new husband did not want him. Scuff had adopted Monk because he thought Monk lacked adequate knowledge of dockside life to do his job and needed someone like Scuff to look after him. Hester he had grown close to more reluctantly, in small steps, both of them being careful, afraid of hurt. The whole arrangement had begun tentatively on all sides, but over the year it had become comfortable.

“What is it?” Hester repeated more urgently.

“We found the body of a woman on Limehouse Pier at dawn yesterday,” Monk replied, putting his folded papers on his chair and then sittingon them. “Badly mutilated. Hoped we’d keep the worst of it out of the papers, but we haven’t. They’re making a meal of it.”

Her face tightened a little with only a tiny movement of muscles. “Who is she? Do you know?”

“Not yet. From what I could tell, she looked ordinary enough, poor but respectable. Middle forties, at a guess.” An image of the woman’s body came back to his mind. Suddenly he felt tired and chilled again, as if the lights had gone out, although the kitchen was bright and warm and full of clean, homey smells.

“The surgeon said the mutilation was done after she was dead,” he went on. “The papers didn’t say that.”

Hester looked at him thoughtfully for a moment, as if she was going to ask him something. Then she changed her mind and served his breakfast of bacon, eggs, and toast, carrying the hot plate with a tea towel and setting it down in front of him. The butter and marmalade were already on the table. She made the tea and brought it over, steam coming gently from the spout of the pot.

Scuff arrived at the door, boots in his hands. He put them down in the hall and came in, looking first at Monk, then at Hester. In spite of almost a year here he was still thin, small for his age, his shoulders narrow. But now his hair was thick and shiny, and there were no blemishes on his fair skin.

“Are you hungry?” Hester inquired, as if it were a question.

He grinned and sat down in what he now regarded as his chair.

“Yeah. Please.”

She smiled and served him the same as she had Monk. He would eat it all, then look hopefully around for more. It was a comfortable pattern, repeated every morning.

“Wo’s wrong?” Scuff regarded Monk with a frown. “Can I ’elp?”

“Not yet, thank you,” Monk assured him, looking up and meeting his eyes so Scuff would know he was serious. “Nasty case, but not mine, at least not yet.” He knew that since it was in the newspapers, Scuff would unquestionably hear about it, but for now they could still have a few hours’ peace. Since living here in

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher