![William Monk 18 - A Sunless Sea]()

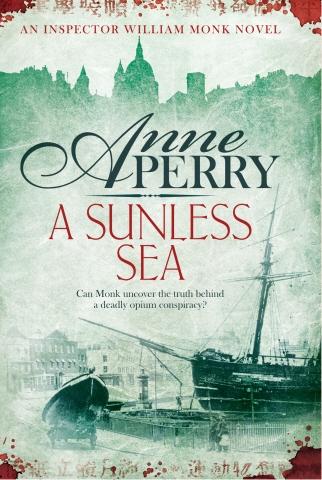

William Monk 18 - A Sunless Sea

punishable very seriously. The prime minister would never ignore what Joel Lambourn had told him of the evil that opium in such a form caused. Your husband, addicted as he was, would sink into despair, and perhaps death. I don’t know whether that mattered to you—perhaps not. It might even have been convenient. But Sinden Bawtry would be finished by such a bill. The wealth he so lavishly spends on his career, and his philanthropy, would dry up. If he continued to sell the opium, then he would become a criminal before the law, ending his days in prison. And you would’ve done anything to prevent that.”

He stopped to draw breath.

“I don’t know whether Dinah guessed at any of this.” He plunged on. “I think not. She believed in her husband, believed that he would not have killed himself. And she knew that she had not killed Zenia. I think it was you, Mrs. Herne, who posed as Dinah in the shops in Copenhagen Place, already knowing perfectly well where Zenia lived, but creating a scene in order to be remembered. You knew Zenia, as she knew you. She trusted you, and quite willingly met you on the evening of her death, just as Joel had met you on the evening of his.”

The court was motionless; no one interrupted him now, even by sigh or gasp.

“You walked with her to the river,” he went on. “Perhaps you even stood together on the pier and watched the light fade over the water, as she loved to do. Then you struck her so hard she collapsed. Perhaps she was dead even as she fell to the ground.

“Then in the darkness you cut her open, possibly with the same blade as you had used to slit your brother’s wrists. You tore out her entrails and laid them across her and onto the ground, to make as hideousa crime as you could, knowing that the newspapers would write headlines about it.

“Public opinion would never allow the police to leave such a murder unsolved. They would eventually find the clues you had laid leading to Dinah, and she would at last be silenced. No one would believe her protests of innocence. She was half mad with grief; and you had reason and sanity, and an unblemished reputation on your side. Who was she? The mistress of a bigamist with a wife he still kept on the side, or so it appeared.”

He looked up at her now with both awe and disgust.

“You very nearly got away with it. Joel would be dead and dishonored. Zenia had served her purpose and would be remembered only as the victim of a terrible crime of revenge. Dinah would be hanged as one of the most gruesome female murderers of our time. And you would be free to continue your love affair with a rich, famous, and very handsome man, possibly even marry him when your husband’s addiction ended his life. And Sinden Bawtry would forever owe you his freedom from dishonor and disgrace.”

He took a deep breath. “Except, of course, that he does not love you. He used you, just as you used Zenia Gadney, and God knows who else. Surely in time he would also kill you. You have a hold on him that he cannot afford to leave at loose ends, and he will grow tired of your adoration when it is no longer useful to him. It becomes boring to be adored. We do not value that which is given to us for nothing.”

She tried to speak, but no words came to her lips.

“No defense?” Rathbone said quickly. “No more lies? I could pity you, but I cannot afford to. You had no pity for anyone else.” He looked up at Pendock. “Thank you, my lord. I have no more witnesses. The defense rests.”

Coniston said nothing, like a man robbed of speech.

The jury retired and came back within minutes.

“Not guilty,” the foreman said with perfect confidence. He even looked up at Dinah in the dock and smiled, a gentle look of both pity and relief, and something that could have been admiration.

Rathbone asked permission to speak to Pendock in chambers, privately, and he walked out of the court before anyone else could catchhis attention. He did not even look at Hester, Monk, or Runcorn, all waiting.

He found Pendock alone in his chambers, white-faced.

“What now?” the judge asked, his voice hoarse and shaking in spite of his attempt to remain calm.

“I have something that should belong to you,” Rathbone answered. “I don’t wish to carry it around, but if you come to my house at some time of your convenience, you may do with it, and all copies of it, whatever you please. I would suggest acid for the original, and a fire for the copies, which are

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher