![William Monk 18 - A Sunless Sea]()

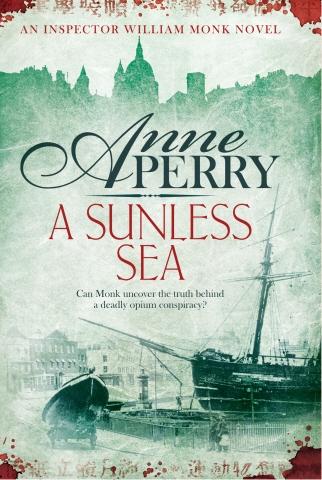

William Monk 18 - A Sunless Sea

someone else was left delicately in the air.

“Zenia?” Coniston repeated. “You are certain?”

Amity stood very stiffly. “Yes. I have never heard of anyone else with the name.”

“And was his wife, Dinah Lambourn, aware of this … arrangement?” Coniston asked.

“I was told that she learned of it,” Amity replied.

“How did she learn?”

“I don’t know. Joel didn’t say.”

“Did he say when she learned?”

“No. At least not to me.”

“Thank you, Mrs. Herne. Again, I am deeply sorry that I had to raise this distressing subject, but the circumstances left me no choice.” He turned to Rathbone. “Your witness, Sir Oliver.”

Rathbone thanked him and rose slowly to his feet. He walked out across the floor toward the witness stand. He could feel the jury’s eyes on him, cautious, ready to blame him if he was the least bit insensitive. They were naturally predisposed against him because he represented a woman accused of a bestial crime. And now, added to that, he was about to ask pointed and cruel questions, adding to this innocent woman’s grief and very natural embarrassment.

“You have already suffered more than enough, Mrs. Herne,” Rathbone began gently. “I shall be as brief with you as I can. I commend you for being so honest regarding your brother’s … tastes. That cannot have been easy for you. You and your brother were close?” He already knew the answer to that from Monk’s questioning of her.

She blinked. In that instant he knew she was considering a lie, and as their eyes met, she decided against it.

“Not until recently,” she admitted. “My husband and I lived some distance away. Visiting was difficult. But we always kept in touch. There were just the two of us, Joel and I. Our parents have been dead a long time.” There was an ache of sadness in her voice, and a loneliness in her face. She was the perfect witness for Coniston.

Rathbone changed his tactics. There was very little, if anything at all, that he could win.

“Did you at that time also come to know your sister-in-law better?”

She hesitated again.

He felt his stomach knot. Should he have asked her that? If she said yes, then she would either defend her, or be seen to betray her. If she said no, she would have to give a reason. He had made an error.

“I tried,” she said guiltily, a slight flush in her cheeks. “I think if things had been different, we might have become close. But when Joel died, she was beside herself with grief, as if she blamed herself …” She tailed off.

In the gallery several people moved, sighed, and rustled fabric or paper.

“Did you blame her?” Rathbone asked clearly.

“No, of course not.” She looked startled.

“It was not her fault that Dr. Lambourn’s work was rejected?”

Coniston made as if to stand up. Rathbone turned to look at him, eyebrows raised. Coniston relaxed again.

“Mrs. Herne?” Rathbone prompted.

“How could it be?” she answered. “That isn’t possible.”

“Should she have … complied with his needs? The ones for which he went to the woman named Zenia?” he suggested.

“I … I …” At last she was stuck for words. She did not look to Coniston for help but lowered her gaze modestly.

Coniston stood up. “My lord, my learned friend’s question is embarrassing and unnecessary. How could Mrs. Herne be—”

Rathbone gave a gracious little wave. “That’s all right, Mrs. Herne. Your silence is answer enough. Thank you. I have no further questions.”

Coniston next called Barclay Herne, and asked him to give thebriefest possible account of Lambourn’s being asked by the government to make a confidential report on the use and sale of certain medicines. Herne added the now-accepted fact that, to his profound regret, Lambourn had become too passionately involved in the issues and it had warped his judgment to the degree that the government had been unable to accept his work.

“How did Dr. Lambourn take your rejection of his report, Mr. Herne?” Coniston said somberly.

Herne allowed grief to fill his expression. “I’m afraid he took it very badly,” he answered, his voice soft and a little husky. “He saw it as some kind of personal insult. I was worried for the balance of his mind. I profoundly regret that I did not take more care, perhaps persuade him to consult a colleague, but I really did not think it would affect him so … frankly, so out of proportion to reality.” He looked miserable,

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher