![Write me a Letter]()

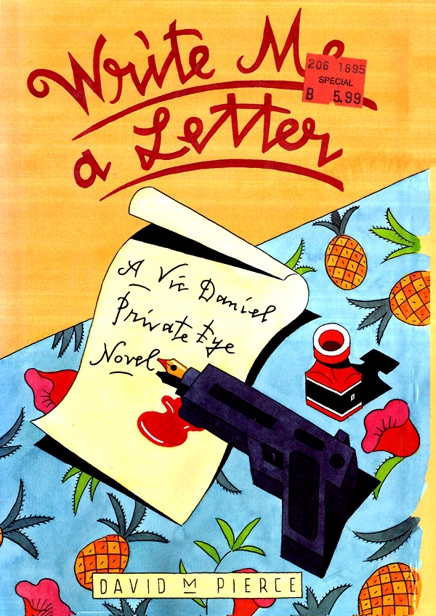

Write me a Letter

She’s in doggy heaven now.”

”To sit shivah is how the Jews honor their dead,” she said. ”I apologize,” I said, blushing to the roots. ”I didn’t know. What does it consist of?”

”Seven days of mourning,” she said. ”Shivah means seven. Officially it is only performed by the immediate family—brothers, sisters, father and mother, sons and daughters—and the deceased must have been buried within three days of his death. 'You could perhaps think of it as a Jewish wake.”

”What do you do?”

”Traditionally, you sit on wooden boxes, although now stools are often used, without shoes. To combat vanity, all mirrors are covered. Food is served, of course, and there’s no lack of conversation, it’s not entirely a sad occasion.”

”Were you related to Solomon?”

”No,” she said, ”he had no relations at all as far as I knew, they were all killed in the Second World War, except one cousin he mentioned once, he was one of the few tank commanders we lost in the Six-Day War. But I wanted to do something so myself and a few friends, we did the best we could.”

”God damn it anyway,” I said, or something equally impolite and meaningless.

”How’s your friend?” she asked then.

”He’s doing terrific,” I said. ”We flew him down here the day before yesterday, he could be out in the world and up to his old tricks again in what, ten days, two weeks?”

”I knew you moved him,” she said. She opened up her purse (also forest green, I neglected to mention) and put an envelope on the desk in front of me. When she leaned forward, her blouse parted slightly; I averted my eyes. Inside the envelope were travelers checks totaling two thousand dollars. ”Half for the plane,” she said. ”The rest for you if you’ll take it.”

”I hope they’re kosher,” I said.

”They are,” she said.

”The half for the plane,” I said. ”Is that my half or Lew’s half?”

”Yours,” she said.

”Oh,” I said. ”Jolly decent of you.” I put the money away in a drawer. ”If I decide it’s too contaminated, I’ll buy you a couple of trees. Who was that old guy, anyway? I hope he was worth it all.”

She rummaged again in her handbag, then slid a sheet of paper across to me. This time I failed to avert my eyes in time and couldn’t help noticing her undergarment was black and lacy, unlike mine, which was sweatstained, fraying around the edges, and getting to be a bigger nuisance than Mickey Rooney at a beach party. Luckily I only had to wear it another couple of days.

The name at the top of the sheet I didn’t recognize although no doubt Nathan Lubinski would have. There followed his date of birth, place of birth—some small town in Austria —school records, and so on. Then came the date of his joining the Nazi party, then the SS with his SS number. Passed some course. Transferred to Essen . Got his commission. When the war started, served with a Waffen-SS group blitzkrieging French, Belgians, and anyone else who had the temerity to resist the mighty Third Reich. He got promoted. Sent as second in command of new extermination camp at Riga . One year later promoted to commandant. Estimated one million (1,000,000) slain 1941—1944. Assumed he escaped late 1944 by boat from Riga or Ventspils, then via Portugal to South America .

”That little guy?” I said. ”It’s unbelievable.”

”Want to see a picture of him as he was then?” she asked me.

”No, thank you,” I said.

”Would you like to know what his particular specialty was?”

”No, thank you,” I said.

”So you tell me,” she said. ”Was it worth it?”

”It’s not a question of worth it,” I said.

”What is it a question of, then?”

”How should I know?” I said. ”Ask the rabbi, maybe he knows. What I do know is you set me up, lady, and good.”

”I’m sorry about that,” she said.

”You’re sorry,” I said. ”I’ve had some time to think about it, and here’s what I think, correct me if I’m wrong. The purpose of the whole number wasn’t for Uncle Theo to recognize Cookie, it was for Cookie to recognize Uncle Theo, and did he ever. I don’t know if they knew each other from a camp or before or after, but as soon as Cookie got one look at him he knew what was involved.”

”After,” said my ex-dream girl. ”Theo tracked him from Argentina to Chile to Mexico . He had him, then he lost him.”

”Theo should stick to picking grapes,” I said. ”Anyway. After a while,

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher