![A Blink of the Screen]()

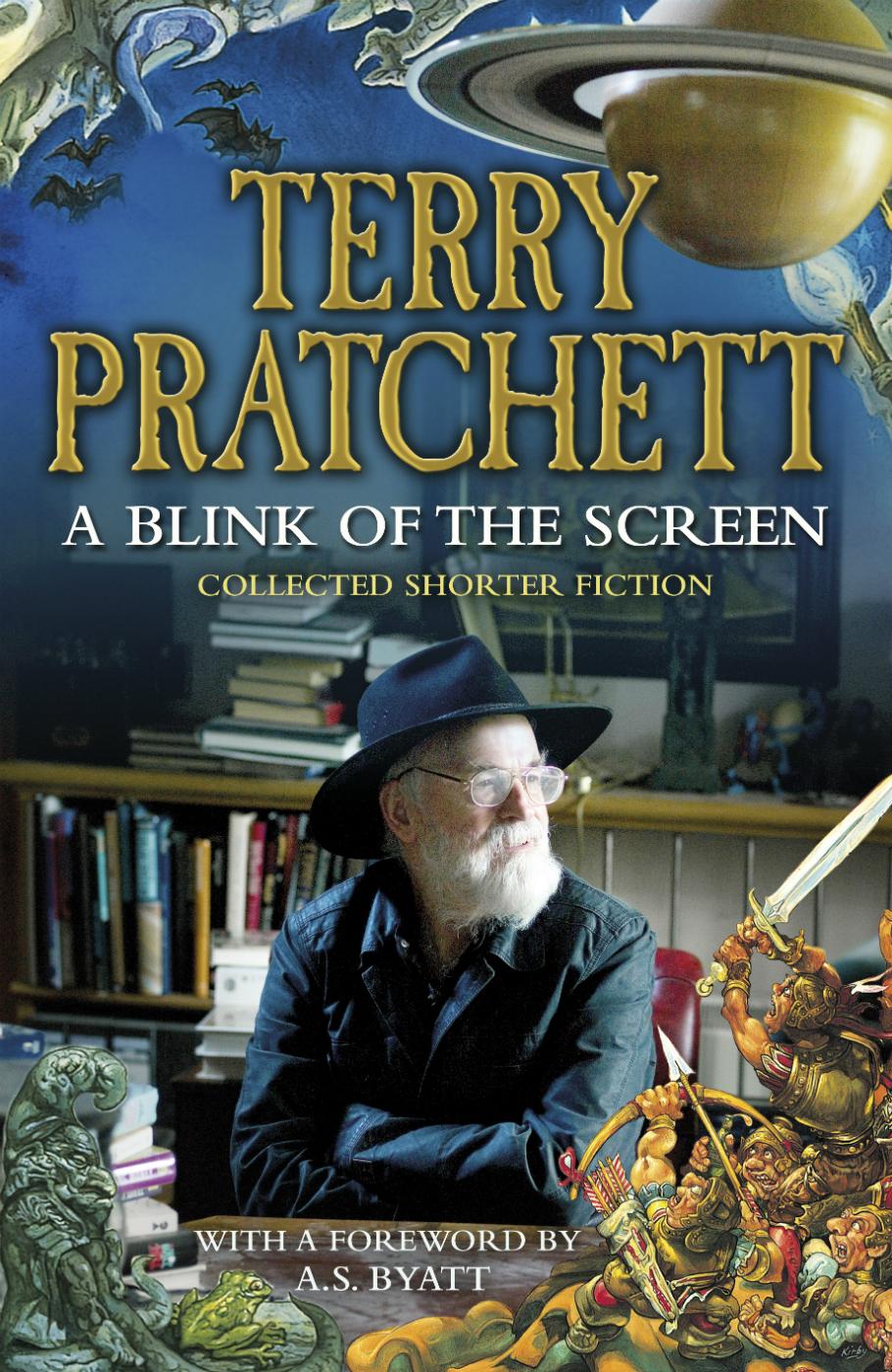

A Blink of the Screen

suggested.

She shrugged. ‘Why should he? He doesn’t carry it from the spring.’

‘Oh.’

But she took to following me around, in what time there was between chores. It’s just as I’ve always said – women have always had a greater stake in technology than have men. We’d still be living in trees, otherwise. Piped water, electric lighting, stoves that you don’t need to shove wood into – I reckon that behind half the great inventors of history were their wives, nagging them into finding a cleaner way of doing the chores.

Nimue trailed me like a spaniel as I tottered around their village, if you could use the term for a collection of huts that looked like something deposited in the last Ice Age, or possibly by a dinosaur with a really serious bowel problem. She even led me into the forest, where I finally found the machine in a thorn thicket. Totally un-repairable. The only hope was that someone might fetch me, if they ever worked out where I was. And I knew they never would, because if they ever did, they’d have been there already. Even if it took them ten years to work it out, they could still come back to the Here and Now. That’s the thing about time-travel; you’ve got all the time in the world.

I was marooned.

However, we experienced travellers always carry a little something to tide us over the bad times. I’d got a whole box of stuff under the seat. A few small gold ingots (acceptable everywhere, like the very best credit cards). Pepper (worth more than gold for hundreds of years). Aluminium (a rare and precious metal in the days before cheap and plentiful electricity). And seeds. And pencils. Enough drugs to start a store. Don’t tell me about herbal remedies – people screamed down the centuries, trying to stop things like dental abscesses with any green junk that happened to be growing in the mud.

She watched me owlishly while I sorted through the stuff and told her what it all did.

And the next day her father cut his leg open with his axe. The brothers carried him home. I stitched him up and, with her eyes on me, treated the wound. A week later he was walking around again, instead of being a cripple at best or most likely a gangrenous corpse, and I was a hero. Or, rather, since I didn’t have the muscles for a hero, obviously a wizard.

I was mad to act like that. You’re not supposed to meddle. But what the hell. I was marooned. I was never going home. I didn’t care. And I could cure, which is almost as powerful as being able to kill. I taught hygiene. I taught them about turnips, and running water, and basic medicine.

The boss of the valley was a decent enough old knight called Sir Ector. Nimue knew him, which surprised me, but shouldn’t have. The old boy was only one step up from his peasants, and seemed to know them all, and wasn’t much richer than they were except that history had left him with a crumbling castle and a suit of rusty armour. Nimue went up to the castle one day a week to be a kind of lady’s maid for his daughter.

After I pulled the bad teeth that had been making his life agony, old Ector swore eternal friendship and gave me the run of the place. I met his son Kay, a big hearty lad with the muscles of an ox and possibly the brains of one, and there was this daughter to whom no one seemed to want to introduce me properly, perhaps because she was very attractive in a quiet kind of way. She had one of those stares that seem to be reading the inside of your skull. She and Nimue got along like sisters. Like sisters that get along well, I mean.

I became a big man in the neighbourhood. It’s amazing the impression you can make with a handful of medicines, some basic science, and a good line in bull.

Poor old Merlin had left a hole which I filled like water in a cup. There wasn’t a man in the country who wouldn’t listen to me.

And whenever she had a spare moment Nimue followed me, watching like an owl.

I suppose at the time I had some dream, like the Connecticut Yankee, of single-handedly driving the society into the twentieth century.

You might as well try pushing the sea with a broom.

‘But they do what you tell them,’ Nimue said. She was helping me in the lab at the time, I think. I call it the lab, it was just a room in the castle. I was trying to make penicillin.

‘That’s exactly it,’ I told her. ‘And what good is that? The moment I turn my back, they go back to the same old ways.’

‘I thought you told me a dimocracy was

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher