![A Lasting Impression]()

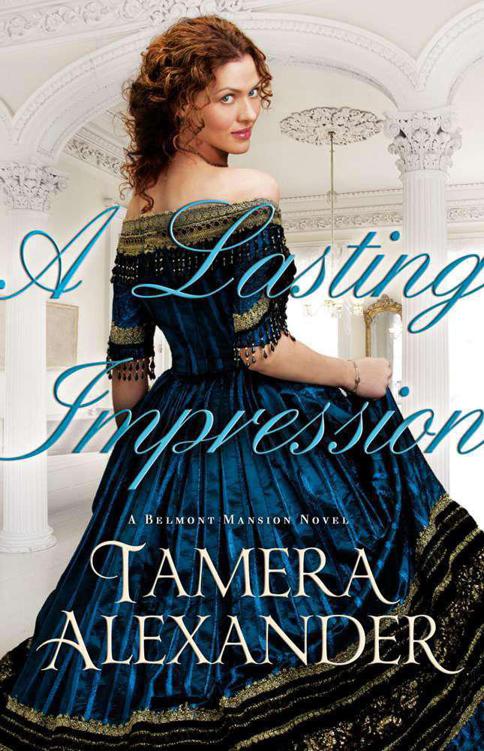

A Lasting Impression

that his primary obligation in this instance—understanding they were both Mrs. Acklen’s employees—was to Adelicia, and to protecting her interests.

He thought of the contents of the envelope again.

Whether Claire was aware of it or not, of all the employees who worked at Belmont, she was in a position to do Adelicia the most harm. As Adelicia’s liaison, Claire was privy to information—both personal and business—that no one else was. Besides him. And Claire had the added insight of reading and responding to Adelicia’s private and social correspondence, as well as managing her personal calendar.

But most importantly, she had won Adelicia’s trust. Completely. That had been clear to him today. What had also been clear was that Adelicia’s motivation behind hosting the upcoming reception was twofold.

He didn’t doubt Adelicia’s sincere desire to honor Madame LeVert. But he had an inkling of how the woman’s mind worked. Octavia LeVert was the most beloved belle in all of Dixie, and Adelicia’s own reputation had suffered in the past couple of years. First due to the cotton fiasco, then when news of her European travels became widespread. And having the mansion redecorated while on the trip hadn’t helped matters either.

He slowed his steps as he approached the next intersection. He waited for a carriage to pass, then continued on to the left. What concerned him most was that while Adelicia was working to repair her reputation—utilizing Claire’s skills to accomplish that—Claire was, in turn, hoping to benefit from Adelicia’s fine standing in the community to achieve her personal goals. Each woman was, in effect, using the other.

And here he was, wedged right in the middle of them both. He glanced up.

The government building loomed ahead, appearing more ominous than the last time he’d visited—the only other time. His stomach knotted.

Inside, the lobby bustled with employees and patrons, the air stagnant and stale. Sutton made his way to the staircase and to the second floor. He approached Colonel Wilmington’s secretary, certain she wouldn’t remem—

“Mr. Monroe.” She smiled. “You’re back.”

Sutton cleared his throat, surprised. “Yes, ma’am, I am. And I’d like to see Colonel Wilmington, if he’s available.”

“He’s in his office, Mr. Monroe, but . . .” She glanced behind her at a closed door that bore a placard with the colonel’s name. “He’s with someone right now. Would you like to wait? It shouldn’t be too long.”

With everything in him, he wanted to leave. “Yes, ma’am. I’ll wait.”

“May I inquire as to what you’re seeing the Colonel about?”

“A legal matter. I’m . . . with Holbrook and Wickliffe. ” Which he was, in a way. Just not in relation to this particular visit.

He declined the secretary’s offer of coffee or tea and took a seat. His mind raced even as his heart beat heavy and sluggish in his chest.

Ten minutes passed, then twenty.

Becoming more tense by the second and needing to occupy his mind, he pulled the envelope from his pocket and opened it. If there was something he needed to know about Claire, he decided he wanted to know sooner rather than later. For Adelicia’s sake, as well as his own.

The report, written in letter style, was surprisingly brief for having taken so long to compile. He scanned it. Claire’s parents, Gustave and Abella Laurent, were originally from France. He’d already known that. About two years ago, they’d moved to New Orleans and had operated a local—he frowned—art gallery.

An art gallery . . . That was something he hadn’t known. And that Claire had failed to mention. He read on. . . .

The gallery was occupied by a gift shop now, the building space having only been leased by the Laurents. The gallery had been one of “lesser consequence,” the report read. Sutton would check with his colleague to be sure, but he guessed that meant it had associated with lesser-known artists, a fact which would have limited Gustave Laurent’s ability to trade stock with the larger galleries, as Sutton had recently learned while preparing for the upcoming trial.

But her association with the art gallery explained where Claire had learned how to paint. At least in part. Her mother, Bella Laurent, died of tuberculosis eight months ago. Claire had told him that. And—Sutton smiled to himself—Bella Laurent had been an artist. Of course she had. Another reason why Claire was so gifted.

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher