![Aftermath]()

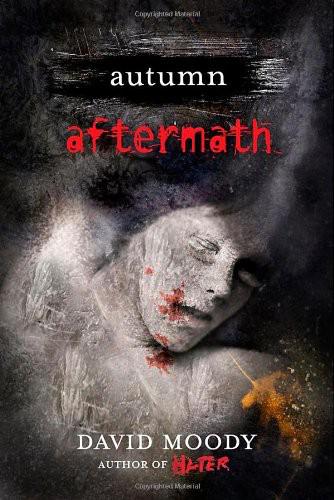

Aftermath

again?”

“Well, I’m not,” he joked, immediately regretting his ill-considered jibe when he saw the expression on her face.

“I can’t believe we ever used to look like this,” she said. “I used to love getting dressed up for a night out with the girls. Getting ready was half the fun. We were usually pissed before we’d even got out the front door.”

“Bloody students,” Cooper grumbled, but she didn’t bite. Instead she thought more about what she’d just said, and tried to picture the others on Cormansey letting their hair down. Would any of them ever bother? Even if they did—all of them piling into the island’s single pub, perhaps, finding a way to play music and glamming up for old times’ sake—she knew it wouldn’t be the same. It’d be like playacting, and would inevitably leave them all feeling emptier than ever. Such a night would only serve to highlight the fact that all of this was gone forevernow. It was time to accept that that part of her life was over.

* * *

A few doors farther down the street, Michael was on his own in another store, collecting baby equipment from a list Emma had drawn up with help from some of the women on the island. She wasn’t even halfway through her pregnancy yet, but he didn’t know if or when he’d get another opportunity like this. He hadn’t felt able to ask any of the other islanders to get this stuff for him—some people had lost kids, others assumed they’d now never have any—and that had been the main reason he’d agreed to come back here himself. Now he stood in the baby store, completely alone, the handwritten shopping list gripped tight in his hand, wishing he could feel even a fraction of the excitement he’d always imagined an expectant father should.

It was strange, he thought. Of all the silent, empty places he’d been since most of the world had died last September, this felt like the quietest, emptiest place of all. It was eerie. He was used to being alone—they all were—but being here took loneliness to another level entirely. Around him, the walls were covered with paintings of fairy-tale characters, oversized letters and numbers, and black-and-white photographs of the faces of innocent toddlers and expectant moms. He couldn’t imagine that this place had ever been quiet like this before. On the rare occasions he’d had to come into stores like this, he’d always been driven out by the sounds of kids crying and the incessant nursery rhyme music being piped through the PA on repeat.

Michael had almost been looking forward to coming here—as much as he looked forward to anything these days—but the reality had proved to be disappointingly grim. He dutifully fetched himself a trolley and began to fill it, ticking items off the list: baby-grows, nappies, bottles, the odd toy, all the powdered milk and food he could find which was still in date with a decent shelf life … As he worked, disappointingly familiar doubts began to reappear. He’d managed to blank them out for a while, but here today on his own with Emma so far away, it was impossible not to think about the future his unborn child might or might not have. There remained a very real possibility—perhaps even a probability—that the baby would die almost immediately after birth. But even if it did survive, what kind of a life would it have to look forward to? He imagined the child growing up on Cormansey and outliving everyone else. Suddenly it didn’t seem too fantastic to believe that, all other things being equal, his and Emma’s child might truly end up being the last person left alive on the face of the planet. How would he or she feel? Michael couldn’t even begin to imagine the loneliness they might experience as their elders gradually passed away. Imagine knowing you were never going to see another person’s face, that no one would ever come if you screamed for help …

Snap out of it , he told himself. Get a fucking grip.

Angry for allowing himself to sound so defeatist, and now moving with much more speed than before, Michael pushed the trolley around into another aisle and then stopped. Lying in front of him was the body of what he assumed had once been a young mom. Judging by the look of the stretched clothing which now hung like tent canvas, flapping over what remained of her emaciated frame, this woman had probably been pregnant when she’d died. Just ahead of her was a pushchair which had toppled over onto its

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher