![Brave New Worlds]()

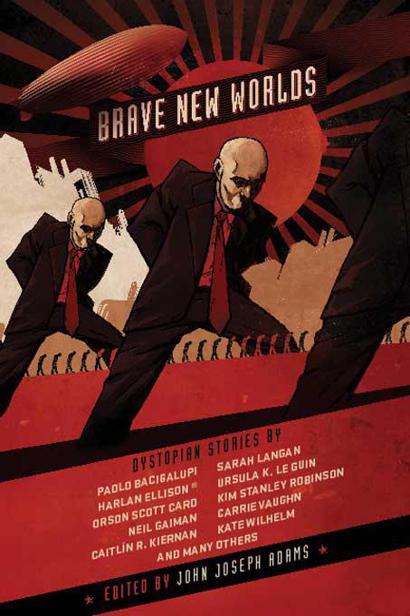

Brave New Worlds

Strange Get Engineered Away

by Cory Doctorow

Cory Doctorow is the author of the novels Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom , Eastern Standard Tribe , Someone Comes to Town Someone Leaves Town , Makers , For the Win , and the dystopian young adult novel Little Brother . His short fiction, which has appeared in a variety of magazines—from Asimov's Science Fiction to Salon.com —has been collected in A Place So Foreign and Eight More and in Overclocked: Stories of the Future Present . He is a four-time winner of the Locus Award, a winner of the Canadian Starburst Award, has been nominated for both the Hugo and Nebula Awards, and in 2000, he won the John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer. Doctorow is also the co-editor of Boing Boing, the online "directory of wonderful things. "

Big Brother is watching you.

When George Orwell wrote those words in 1949, the notion of a surveillance state was the stuff of absolute science fiction. Today, in an era of security cameras, wire taps and radio-frequency ID tags, surveillance is constant, and privacy a privilege. If no one is watching you, it's not because they can't—it's simply because so far, no one has decided it's worthwhile.

But in the future Cory Doctorow describes in our next story, someone has decided to watch everyone, all the time, every day. Just think a moment about what your daily life is like. Have you ever run a red light? Have you stayed parked longer than the meter would allow? Have you ever rounded down on your taxes?

Here is a world where the minor infractions get noticed. Here is a world where everyone is going to get caught sometime and everyone is some kind of criminal. Forget Big Brother. In this dystopian surveillance state, the watchers are more like the Godfather and his dons.

'Cause it's gonna be the future soon,

And I won't always be this way,

When the things that make me weak and strange get engineered away

—Jonathan Coulton, "The Future Soon"

L awrence's cubicle was just the right place to chew on a thorny logfile problem: decorated with the votive fetishes of his monastic order, a thousand calming, clarifying mandalas and saints devoted to helping him think clearly.

From the nearby cubicles, Lawrence heard the ritualized muttering of a thousand brothers and sisters in the Order of Reflective Analytics, a susurration of harmonized, concentrated thought. On his display, he watched an instrument widget track the decibel level over time, the graph overlaid on a 3D curve of normal activity over time and space. He noted that the level was a little high, the room a little more anxious than usual.

He clicked and tapped and thought some more, massaging the logfile to see if he could make it snap into focus and make sense, but it stubbornly refused to be sensible. The data tracked the custody chain of the bitstream the Order munged for the Securitat, and somewhere in there, a file had grown by sixty-eight bytes, blowing its checksum and becoming An Anomaly.

Order lore was filled with Anomalies, loose threads in the fabric of reality—bugs to be squashed in the data-set that was the Order's universe. Starting with the pre-Order sysadmin who'd tracked a $0. 75 billing anomaly back to a foreign spy-ring that was using his systems to hack his military, these morality tales were object lessons to the Order's monks: pick at the seams and the world will unravel in useful and interesting ways.

Lawrence had reached the end of his personal picking capacity, though. It was time to talk it over with Gerta.

He stood up and walked away from his cubicle, touching his belt to let his sensor array know that he remembered it was there. It counted his steps and his heartbeats and his EEG spikes as he made his way out into the compound.

It's not like Gerta was in charge—the Order worked in autonomous little units with rotating leadership, all coordinated by some groupware that let them keep the hierarchy nice and flat, the way that they all liked it. Authority sucked.

But once you instrument every keystroke, every click, every erg of productivity, it soon becomes apparent who knows her shit and who just doesn't. Gerta knew the shit cold.

"Question," he said, walking up to her. She liked it brusque. No nonsense.

She batted her handball against the court wall three more times, making long dives for it, sweaty grey hair whipping back and forth, body arcing in graceful flows. Then she caught the ball and tossed it into the basket by his feet.

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher