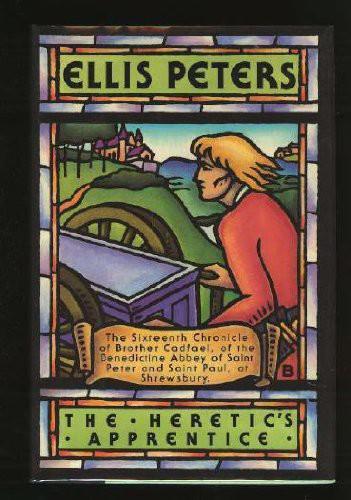

![Brother Cadfael 16: The Heretic's Apprentice]()

Brother Cadfael 16: The Heretic's Apprentice

envoy, hung close and convincing at his elbow, stiffening a mind already disposed to rigidity. As between his abbot and Theobald's vicarious presence Robert might be torn, and would certainly endeavour to remain compatible with both, but in extremes he would go with Gerbert. Cadfael, watching him manipulating inward argument, with devoutly folded hands, arched silver brows, and tightly pursed mouth, could almost find the words in which he would endorse whatever Gerbert said, while subtly refraining from actually echoing it. And if he knew his man, so did the abbot. As for Gerbert himself, Cadfael had a sudden startling insight into a mind utterly alien to his own. For the man really had, somewhere in Europe, glimpsed yawning chaos and been afraid, seen the subtleties of the devil working through the mouths of men, and the fragmentation of Christendom in the eruption of loud-voiced prophets bursting out of limbo like bubbles in the scum of a boiling pot, and the dispersion into the wilderness in the malignant excesses of their deluded followers. There was nothing false in the horror with which Gerbert looked upon the threat of heresy, though how he could find it in an open soul like Elave remained incomprehensible.

Nor could the abbot afford to oppose the archbishop's representative, however true it might be that Theobald probably held a more balanced and temperate opinion of those who felt compelled to reason about faith than did Gerbert. A threat that troubled Pope, cardinals, and bishops abroad, however nebulous it might feel here, must be taken seriously. There is much to be said for being an island off the main. Invasions, curses, and plagues are slower to reach one, and arrive so weakened as to be almost exhausted beforehand. Yet even distance may not always be a perfect defence.

"You have heard," said Radulfus, "an offer which is generous, and comes from one whose good faith may be taken for granted. We need only debate what is right for us to do in response. I have only one reservation. If this concerned only my monastic household, I should have none. Let me hear your view, Canon Gerbert."

There was no help for it, he would certainly be expressing it very forcibly, as well compel him to speak first, so that his rigors could at least be moderated afterward.

"In a matter of such gravity," said Gerbert, "I am absolutely against any relaxation. It is true, and I acknowledge it, that the accused has been at liberty once, and returned as he was pledged to do. But that experience may itself cause him to do otherwise if the chance is repeated. I say we have no right to take any risk with a prisoner accused of such a perilous crime. I tell you, the threat to Christendom is not understood here, or there would be no dispute, none! He must remain under lock and key until the cause is fully heard."

"Robert?"

"I cannot but agree," said the prior, looking studiously down his long nose. "It is too serious a charge to take even the least risk of flight. Moreover, the time is not wasted while he remains in our custody. Brother Anselm has been providing him with books, for the better instruction of his mind. If we keep him, the good seed may yet fall on ground not utterly barren."

"True," said Brother Anselm without detectable irony, "he reads, and he thinks about what he reads. He brought back more than silver pence from the Holy Land. An intelligent man's baggage on such a journey must be light, but in his mind he can accumulate a world." Wisely and ambiguously he halted there, before Canon Gerbert should wind his slower way through this speech to understanding, and spy an infinitesimal note of heresy in it. It is not wise to tease a man with no humour in him.

"It seems I should be outvoted if I came down on the side of release," said the abbot dryly, "but it so chances that I, too, am for continuing to hold the young man here in the enclave. This house is my domain, but jurisdiction has already passed out of my hands. We have sent word to the bishop, and expect to hear his will very soon. Therefore the judgment is now with him, and our part is simply to ensure that we hand over the accused to him, or to his representatives, as soon as he makes his will known. I am now no more in this matter than the bishop's agent. I am sorry, Master Girard, but that must be my answer. I cannot take you as bail, I cannot give you custody of Elave. I can promise you that he shall come to no harm here in my house. Nor suffer any further

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher