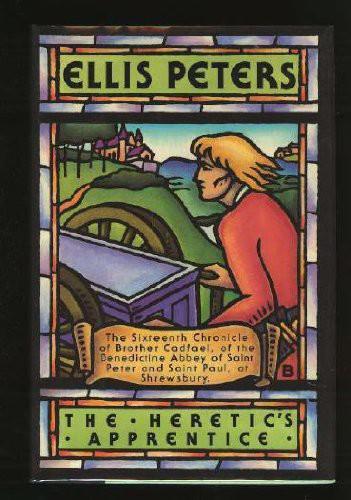

![Brother Cadfael 16: The Heretic's Apprentice]()

Brother Cadfael 16: The Heretic's Apprentice

violence," he added with intent, if without emphasis.

"Then at least," said Girard quickly, accepting what he saw to be unalterable, but alert to make the most of what ground was left to him, "can I be assured that the bishop will give me as fair a hearing, when it comes to a trial, as you have given me now?"

"I shall see to it that he is informed of your wish and right to be heard," said the abbot.

"And may we see and speak with Elave, now that we are here? It may help to settle his mind to know that there is a roof and employment ready for him, when he is free to accept them."

"I see no objection," said Radulfus.

"In company," added Gerbert quickly and loudly. "There must be some brother present to witness all that may be said."

"That can quite well be provided," said the abbot. "Brother Cadfael will be paying his daily visit to the young man after chapter, to see how his injuries are healing. He can conduct Master Girard, and remain throughout the visit." And with that he rose authoritatively to cut off further objections that might be forming in Canon Gerbert's undoubtedly less agile mind. He had not so much as glanced in Cadfael's direction. "This chapter is concluded," he said, and followed his secular visitors out of the chapter house.

Elave was sitting on his pallet under the narrow window of the cell. There was a book open on the reading desk beside him, but he was no longer reading, only frowning over some deep inward consideration drawn from what he had read, and by the set of his face he had not found much that was comprehensible in whichever of the early fathers Anselm had brought him. It seemed to him that most of them spent far more time in denouncing one another than in extolling God, and more venom on the one occupation than fervour on the other. Perhaps there were others who were less ready to declare war at the drop of a word, and actually thought and spoke well of their fellow-theologians, even when they differed, but if so all their books must have been burned, and possibly they themselves into the bargain.

"The longer I study here," he had said to Brother Anselm bluntly, "the more I begin to think well of heretics. Perhaps I am one, after all. When they all professed to believe in God, and tried to live in a way pleasing to him, how could they hate one another so much?"

In a few curiously companionable days they had arrived at terms on which such questions could be asked and answered freely. And Anselm had turned a page of Origen and replied tranquilly: "It all comes of trying to formulate what is too vast and mysterious to be formulated. Once the bit was between their teeth there was nothing for it but to take exception to anything that differed from their own conception. And every rival conception lured its conceiver deeper and deeper into a quagmire. The simple souls who found no difficulty and knew nothing about formulae walked dry-shod across the same marsh, not knowing it was there."

"I fancy that was what I was doing," said Elave ruefully, "until I came here. Now I'm bogged to the knees, and doubt if I shall ever get out."

"Oh, you may have lost your saving innocence," said Anselm comfortably, "but if you are sinking it's in a morass of other men's words, not your own. They never hold so fast. You have only to close the book."

"Too late! There are things I want to know now. How did Father and Son first become three? Who first wrote of them as three, to confuse us all? How can there be three, all equal, who are yet not three but one?"

"As the three lobes of the clover leaf are three and equal but united in one leaf," suggested Anselm.

"And the four-leaved clover, that brings luck? What is the fourth, humankind? Or are we the stem of the threesome, that binds all together?"

Anselm shook his head over him, but with unperturbed serenity and a tolerant grin. "Never write a book, son! You would certainly be made to burn it!"

Now Elave sat in his solitude, which did not seem to him particularly lonely, and thought about this and other conversations which had passed between precentor and prisoner during the past few days, and seriously considered whether a man was really the better for reading anything at all, let alone these labyrinthine works of theology that served only to make the clear and bright seem muddied and dim, by clothing everything they touched in words obscure and shapeless as mist, far out of the comprehension of ordinary men, of whom the greater part of the human

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher