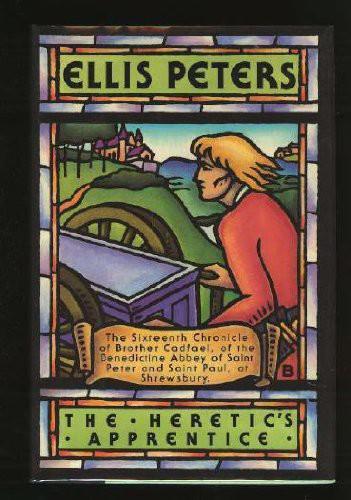

![Brother Cadfael 16: The Heretic's Apprentice]()

Brother Cadfael 16: The Heretic's Apprentice

an important personage, to whose reception the hierarchies of the house were assembling busily. Brother Porter had come in a flurry of skirts to take one bridle, Brother Jerome was contending with a groom for another one, Prior Robert was approaching from the cloister at his longest stride, Brother Denis hovered, not yet certain whether the newcomer would be housed in the guest hall or with the abbot. A flutter of brothers and novices hung at a respectful distance, ready to run any errands that might arise, and three or four of the schoolboys, sensibly withdrawn out of range of notice and censure, stood frankly staring, all eyes and ears.

And in the middle of this flurry of arrival stood Deacon Serlo, just dismounted from his mule and shaking out the skirts of his gown. A little dusty from the ride, but as rounded and pink-cheeked and wholesome as ever, and decidedly happier now that he had brought his bishop with him, and could leave all decisions to him with a quiet mind.

Bishop Roger de Clinton was just alighting from a tall roan horse, with the vigour and spring of a man half his age. For he must, Cadfael thought, be approaching sixty. He had been bishop for fourteen years, and wore his authority as easily and forthrightly as he did his plain riding clothes, and with the same patrician confidence. He was tall, and his erect bearing made him appear taller still. A man austere, competent, and of no pretensions because he needed none, there was something about him, Cadfael thought, of the warrior bishops who were becoming a rare breed these days. His face would have done just as well for a soldier as for a priest, hawk-featured, direct and resolute, with penetrating grey eyes that summed up as rapidly and decisively as they saw. He took in the whole scene about him in one sweeping glance, and surrendered his bridle to the porter as Prior Robert bore down on him all reverence and welcome.

They moved off together towards the abbot's lodging, and the group broke apart gradually, having lost its centre. The horses were eased of their saddlebags and led away to the stables, the hovering brothers dispersed about their various businesses, the children drifted off in search of other amusement until they should be rounded up for their early supper. And Cadfael thought of Elave, who must have heard, distantly across the court, the sounds that heralded the coming of his judge. Cadfael had seen Roger de Clinton only twice before, and had no means of knowing in what mood and what mind he came to this vexed cause. But at least he had come in person, and looked fully capable of wresting back the responsibility for his diocese and its spiritual health from anyone who presumed to trespass on his writ.

Meantime, Cadfael's immediate business was to find Fortunata. He approached the porter with his enquiry. "Where am I likely to find Girard of Lythwood's daughter? They told me at the house she would be here."

"I know the girl," said the porter, nodding. "But I've seen nothing of her today."

"She told them at home she was coming down here. Soon after dinner, so the mother told me."

"I've neither seen nor spoken to her, and I've been here most of the time since noon. An errand or two to do, but I was only a matter of minutes away. Though she may have come in while my back was turned. But she'd need to speak to someone in authority. I think she'd have waited here at the gate until I came."

Cadfael would have thought so, too. But if she'd caught sight of the prior as she waited, or Anselm, or Denis, she might very well have accosted one of them with her petition. Cadfael sought out Denis, whose duties kept him most of the time around the court, and within sight of the gate, but Denis had seen nothing of Fortunata. She was acquainted now with Anselm's little kingdom in the north walk; she might have made her way there, seeking for someone she knew. But Anselm shook his head decidedly, no, she had not been there. Not only was she not to be found within the precinct now, but it seemed she had not set foot in it all that day.

The bell for Vespers found Cadfael hovering irresolute over what he ought to do, and reminded him sternly of his obligations to the vocation he had accepted of his own free will, and sometimes reproached himself for neglecting. There are more ways of approaching a problem than by belligerent action. The mind and the will have also something to say in the unending combat. Cadfael turned towards the south porch and

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher