![Buried Prey]()

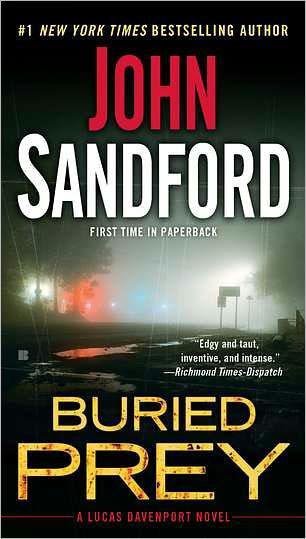

Buried Prey

jobs.”

They found friends and relatives, but nobody knew anything about the killing, and Lucas tended to believe them. Smith, they said, was out doing his thing, which mostly involved wandering around, talking to his homeys. Everybody knew he’d been pounding the crack, and sometimes sold it, and was often holding. So the belief was, somebody needed some crack and they took it.

One guy angrily told them that “That shit is everywhere and it’s fuckin’ up everybody and you ain’t doing a damn thing about it. Not a damn thing.”

Del told him, “I don’t know what to do. You tell me what to do.”

“Do something,” the guy said. “Anything. Arrest them. Put them in jail. They’re a buncha animals, they’re fuckin’ up the whole neighborhood. If we were white, you’d be all over it.”

His wife was standing behind him, arms crossed, nodding.

MOVING AROUND with Del felt weird.

As a uniformed cop, Lucas generally assumed that the people with whom he came in contact were the enemy, until proven different. In the course of covering traffic accidents or making traffic stops, breaking up fights, chasing down robbers or burglars, calling ambulances, talking to victims, uniforms really didn’t need to project much empathy. They were like the army: not there to make friends. And sometimes, rolling through the dark across hostile neighborhoods, inside a car filled with weapons, radios, and lights, he felt like he was in an army, and in hostile territory.

Del, on the other hand, solicited help, listened carefully, displayed great patience, and when the guy went off about crack, he was nodding in agreement, and when the guy finished, he said, “Don’t tell the boss I said this, but I agree with you.”

And he got some cooperation, but no real information, probably, Lucas thought, because nobody had any.

AT TEN O’CLOCK, Del had gotten involved in a convoluted discussion with a minister who’d once run a church that Smith and his mother had gone to. Lucas had drifted off down the street, toward the corner where they’d parked, when he saw a thin young white man walking toward the same corner, from the right-angle street. The man was wearing what cops had called a pimp hat, a widebrimmed fuzzy thing that had gone out of fashion sometime in the seventies, when disco died. Long knotted Rasta braids flowed out from under the hat, and Lucas said, aloud, “Randy.”

The man stopped, saw Lucas, did a double take, turned, and started running. Lucas went after him, fifty yards behind.

The thing was, Randy Whitcomb could hoof it, like skinny people often can. He wasn’t in the same class athletically as Lucas, but he wasn’t carrying the weight, either. Lucas heard Del shout, “Hey! Hey!” as he went around the corner, and then the race was on. Lucas could close by ten yards or so every short block, but there was traffic. Sometimes he caught it wrong, going across the street, and Randy stretched his lead, and sometimes Randy caught it wrong, and lost ground. Five blocks and Lucas was getting close, fifteen yards back, and Randy swerved into an alley and as he turned, Lucas caught a flash of plastic going over a hedge; so Randy had off-loaded his crack, coke, or grass, hoping that Lucas hadn’t seen it.

Toward the end of the block, Lucas was four feet behind him, then two feet: Randy glanced back in desperation, hearing the footsteps, and lost another foot in looking, and Lucas hit him between the shoulder blades. Randy went down on his face and Lucas was on top of him, one hand on Randy’s neck, his weight on Randy’s upper back.

“You little cocksucker, I told you to get out of my part of town,” Lucas said. He banged Randy’s face on the alley’s concrete one time, then maneuvered to put the cuffs on. “What’d you throw in that bag, Randy? Yeah, I saw it. You got a little crack in there? You got five years in there?”

“I’m gonna kill you, you motherfucker,” Randy said. “I’m gonna cut your fuckin’ nuts off.”

Randy Whitcomb was a twenty-year-old refugee from suburban St. Paul. He gave every sign of believing that he was a black pimp, though he was so pale that he almost glowed in the darkness of the alley. Not only did he believe that he was black, but a stereotypical TV gangster black, with the fuzzy hat, the cocaine fingernails, the braids, and even a ghetto accent, picked up from MTV. It might have been laughable, if he hadn’t been such an evil little

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher