![Cyberpunk]()

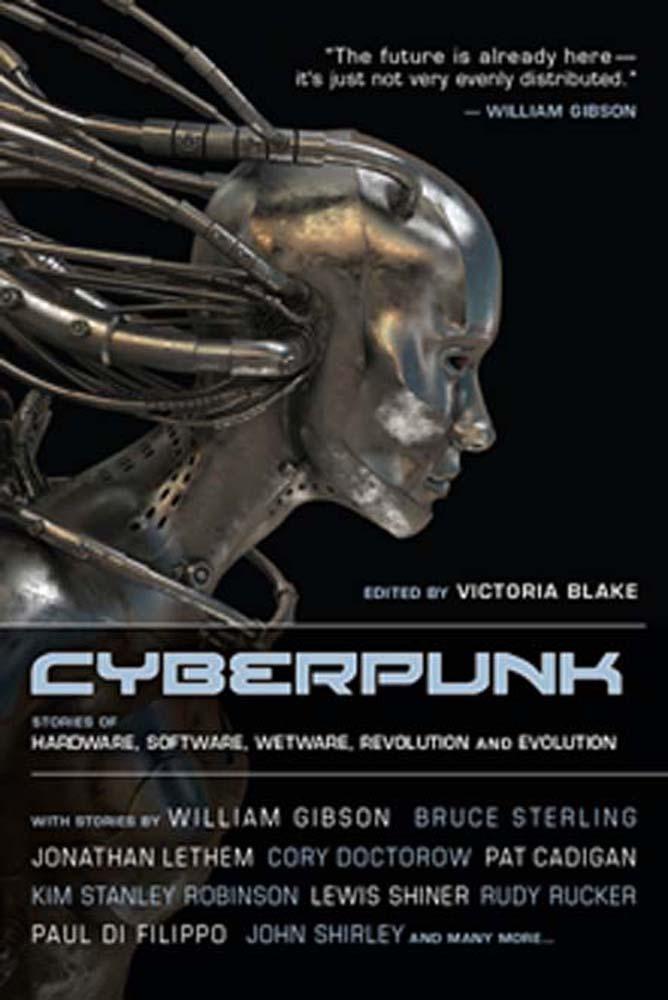

Cyberpunk

plenty of problems.”

Cambridge smiled, humoring him. “Sure you do.”

She opened a door, steps led down. When he realized they were going underground, he understood the dazzling truth. She wasn’t leading him to a bargaining rendezvous with the cadre. She had brought him straight to the goods. The room was shadowy, echoing, with a low and bowing ceiling and a strange incline. The walls, replying to Cambridge’s pencil light, gleamed phosphorescent pale.

“What is this place?”

“It was a swimming pool,” she said. “Olympic pool. It’s been drained and boarded over for years. No water. Rest of the building’s derelict.”

She’d changed into pants, jacket, and a sweater. The rain had made the night cool. Her clothes were as squalid, strange-colored, and ill-fitting as the things the men wore, but not filthy. She pulled a clunky black plastic remote out of her waistband and keyed lights. Must be a generator on site.

Johnny stared. The glass and ceramic labyrinth: the vats. It was the real thing, a coralin plant in full production. He’d spent time in legal protein-chip production, in his apprenticeship—if only in virtuality. It wouldn’t have helped. The processing here was too makeshift to be precisely recognizable. But he’d also been tutored, unofficially, by people who knew the wild side.

He took the time to settle Bella on his shoulders. She had woken up in the pickup, but only to ask a few drowsy questions. What’s her name . . . What’s this car’s name. She was asleep again (and the pickup was called Laetitia). He was proud of her. She was really the perfect child.

“I can make tape?”

Cambridge nodded. “That’s the deal, eejay. We’ll get you away from Micane. You tell the folks back home what we have here.”

He mugged amazement, let her know how thrilled he was to find this spore of civilization outside the citadel: wondering all the while where the rest of the group was, where they’d gotten the starter, all sorts of questions to which he ought to get answers. But he already knew that Cambridge was going to tell him everything. He was stunned by her group’s trust, embarrassed by the power of his job’s reputation.

It had been obvious before the end of the twentieth century that the future of data-processing and telecoms was in photochemistry. Chlorophyll in green plants converts light—energy into excited molecules without thinking twice about it. The “living chip” was inevitable: compact and fast. They called the magic stuff of the semi-living processors “blue clay” because the original protein goop was blue-green in color. Embedded in a liquid crystalline membrane, blue clay became a single surface of endlessly complex interconnections. Under massive magnification it looked like a coral: hence the other name, coralin. Clay? Because you can make it do anything.

So much for the technology. But then the networks, silicon and gallium-arsenide based, had crashed in the explosion of virus infection that ended the century. Coralin wasn’t greatly superior at that point, but it was immune to the plagues. In a deteriorating political situation—a foundering economy, wave upon wave of environmental disasters—the blue clay had become political dynamite. It meant power.

Diamonds? It was a stupid cover, but good enough for the spur of the moment. Out here, a coralin plant was worth more than a truckload of gems. If the masses who lived outside the citadels could build themselves some modern data processing they could hook up into the city networks. They’d be up and running again, and the elite who lived indoors would be running scared. The amazing thing was that more of the masses didn’t try. They accepted, with chilling calm, that a certain way of life was over. They had their own world with its own rules, and the cities were on another planet.

Johnny made tape, describing how it really was a coralin plant, and the journey he’d made to find it. He walked the aisles, the 360 cam on his headset taking in every angle. Cambridge stayed off camera. She didn’t want to wave to the public.

He finished. They faced each other: two nodes of a diffuse molecular machine, linked by the lock and key action of certain key phrases hoicked out of the romance of molecular technology. The living meaning, not like the old technology, change yourself to fit what’s coming at you . Johnny was uneasy. He had not deceived her, not actively. But she was deceived, and it was

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher