![Cyberpunk]()

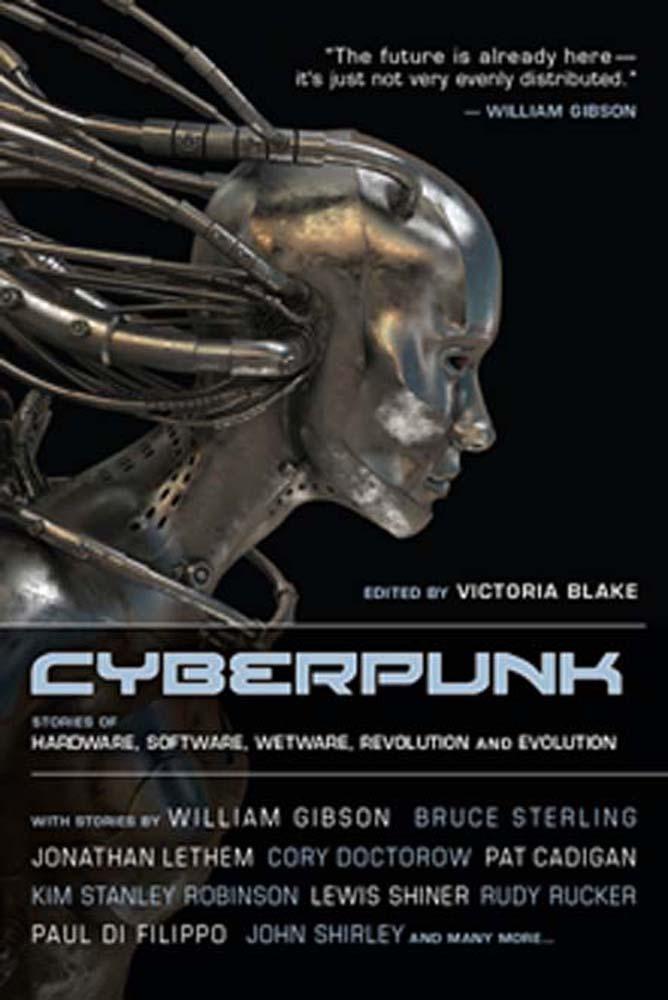

Cyberpunk

writing—stories and novels that were the bastard child of science fiction, with a common-man perspective, a love of tech and drugs, and an affinity for street culture. That most cyberpunk was written by white males didn’t seem to ruffle any feathers. Cyberpunk was new, it was vital, it was irreverent. Most importantly, cyberpunk rocked .

When Sterling and his gang of pranksters shuttered Cheap Truth in 1985, a mere eighteen issues after launch, he declared that the movement was over, it had become too big, and that much of the “original freedom” was lost. “People know who I am,” he wrote, “and they get all hot and bothered by personalities, instead of ideas and issues. CT can no longer claim the ‘honesty of complete desperation.’ That first fine flower of red-hot hysteria is simply gone.” In other words, The Movement had been changed by its acceptance into the smokestack machine. ( Cheap Truth had been mentioned in an issue of Rolling Stone , evidence of it being swallowed whole.) When, in 1986, Sterling published Mirrorshades , the first and some say only true cyberpunk anthology, the movement was consolidated into a particular table of contents, a closed club whose membership was limited to the original cyberpunk writers. In 1991, Lewis Shiner renounced cyberpunk in a New York Times op-ed. When Time ran a cover story about cyberpunks, the cyberpunks themselves were outraged. Counter culture had been embraced by culture. “I hereby declare the revolution over,” Sterling wrote in the final issue of Cheap Truth . “Long live the provisional government.”

Thirty years later, cyberpunk is both very much dead and very much alive. It is dead in the sense that the Reagan years are over, the Cold War is done, straight video has been replaced by CGI, and the achievement of the Xerox machine, once the very pinnacle of technological advancement available to the masses, is being outdone by 3-D printers. But it is very much alive in that cyberpunk was never really about a specific technology or a specific moment in time. It was, and it is, an aesthetic position as much as a collection of themes, an attitude toward mass culture and pop culture, an identity, a way of living, breathing, and grokking our weird and wired world.

Anthology editing is a tricky business. On the one hand, the anthology editor must revere, must even do a little bit of worshipping at the foot of the statue. On the other hand, the editor must be removed enough to see the subject with clear eyes, and to offer an unimpassioned editorial read. But she must also bring just enough of herself to the selection to make the anthology as a whole useful, interesting, unique, timeless, and, hopefully, fun.

In putting together this collection, I have tried to do four things. The first—spurred by the worshipper within me—is to pay homage to cyberpunk beginnings. To that end, this collection contains reprints of cyberpunk gems that are now difficult to find—“Mozart in Mirrorshades” by Bruce Sterling and Lewis Shiner is one of my personal favorites—and it showcases stories by the founding or first-generation cyberpunk authors—Rudy Rucker, John Shirley, Greg Bear, and Paul Di Filippo among them—that weren’t in the original collections.

Second, the critic in me wanted to offer an as-complete-as-possible look at cyberpunk themes and topics. Some of my favorites include the low-life of the Low Teks in William Gibson’s “Johnny Mnemonic,” the imbedded digital brains of David Marusek’s “Getting to Know You,” the drugs and outlaws of Gwyneth Jones’s “Blue Clay Blues,” the multi-mind madness of John Shirley’s “Wolves of the Plateau,” the body augmentation of James Patrick Kelly’s “Mr. Boy,” and the environmental meltdown of Paul Di Filippo’s “Life in the Anthropocene.”

One story from this group deserves a special explanation: “Down and Out in the Year 2000,” by Kim Stanley Robinson, occupies a unique position in the cyberpunk cannon as perhaps the solitary story to critique the cyberpunk reverence for “the street.” “I was living in Washington DC in the summer of 1985,” Robinson wrote me in an email, after I requested some information about the genesis of the story, “hanging out in Dupont Circle park and the smaller park outside our apartment. Watching the people there, I began to think that the cyberpunks were white middle-class people like me, and they had no idea; ‘street smart’

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher