![Dark Rivers of the Heart]()

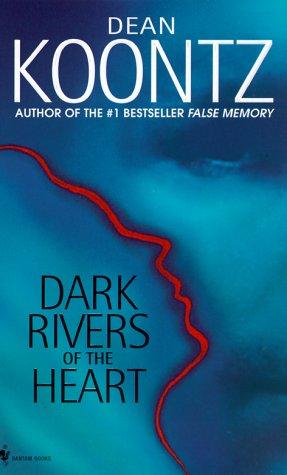

Dark Rivers of the Heart

back end continued to arc to the left.

The river pushed hard on the passenger side, surging halfway up the windows. In turn, as the driver's side of the truck was shoved fully around toward the narrow sluiceway, it created a small swell that rose over the windowsill. The back end slammed into the second gatepost, and water poured inside, onto Spencer, carrying the dead rodent, which had remained in the orbit of the truck.

The rat slipped greasily through his upturned palms and onto the seat between his legs. Its stiff tail trailed across his right hand.

The catacombs. The fiery eyes watching from the shadows. The room, the room, the room at the end of nowhere.

He tried to scream, but what he heard was a choked and broken sobbing, like that of a child terrified beyond endurance.

Possibly half paralyzed from the blow to his head, without a doubt paralyzed by fear, he still managed a spasmodic twitch of both hands, casting the rat off the seat. It splashed into a calf-deep pool of muddy water on the floor. Now it was out of sight. But not gone.

Down there. Floating between his legs.

Don't think about that.

He was as dizzy as if he had spent hours on a carousel, and a fun-house darkness was bleeding in at the edges of his vision.

He wasn't sobbing any more. He repeated the same two words, in a hoarse, agonized voice: "I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry

.

In his deepening delirium, he knew that he was not apologizing to the dog or to Valerie Keene, whom he would now never save, but to his mother for not having saved her, either. She had been dead for more than twenty-two years. He had been only eight years old when she'd died, too small to have saved her, too small then to feel such enormous guilt now, yet "I'm sorry" spilled from his lips.

The river industriously shoved the Explorer deeper into the sluiceway, although the truck was now entirely crosswise to the flow.

Both front and rear bumpers scraped and rattled along the rock walls.

The tortured Ford squealed, groaned, creaked: It was at most one inch shorter from back to front than the width of the water-smoothed gap through which it was struggling to be borne. The river wiggled it, wrenched it, alternately jammed and finessed it, crumpled it at each end to force it forward a foot, an inch, grudgingly forward.

Simultaneously a duall the tremendous ower of the thwarted currents actually lifted the truck a foot. The dark water surged against the passenger side, no longer halfway up the windows on that flank but swirling at the base of them.

Rocky remained down in the half-flooded leg space, enduring.

When Spencer had quelled his dizziness with sheer willpower, he saw that the spine of rock bisecting the arroyo was not as thick as he had thought. From the entrance to the exit of the sluiceway, that corridor of stone would measure no more than twelve feet.

The jackhammering river pushed the Explorer nine feet into the passage, and then with a skreek of tearing metal and an ugly binding sound, the truck wedged tight. If it had made only three more feet, the Explorer would have flowed with the river once more, clear and free. So close.

Now that the truck was held fast, no longer protesting the grip of the rock, the rain was again the loudest sound in the day. It was more thunderous than before, although falling no harder. Maybe it only seemed louder because he was sick to death of it.

Rocky had scrambled onto the seat again, out of the water on the floor, dripping and miserable.

"I'm so sorry," Spencer said.

Fending off despair and the insistent darkness that constricted his vision, incapable of meeting the dog's trusting eyes, Spencer turned to the side window, to the river, which so recently he had feared and hated but which he now longed to embrace.

The river wasn't there.

He thought he was hallucinating.

Far away, veiled by furies of rain, a range of desert mountains defined the horizon, and the highest elevations were lost in clouds.

No river dwindled from him toward those distant peaks. In fact, nothing whatsoever seemed to lie between the truck and the mountains.

The vista was like a painting in which the artist had left the foreground of the canvas entirely blank.

Then, almost dreamily, Spencer realized that he had not seen what

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher