![Dead Tomorrow]()

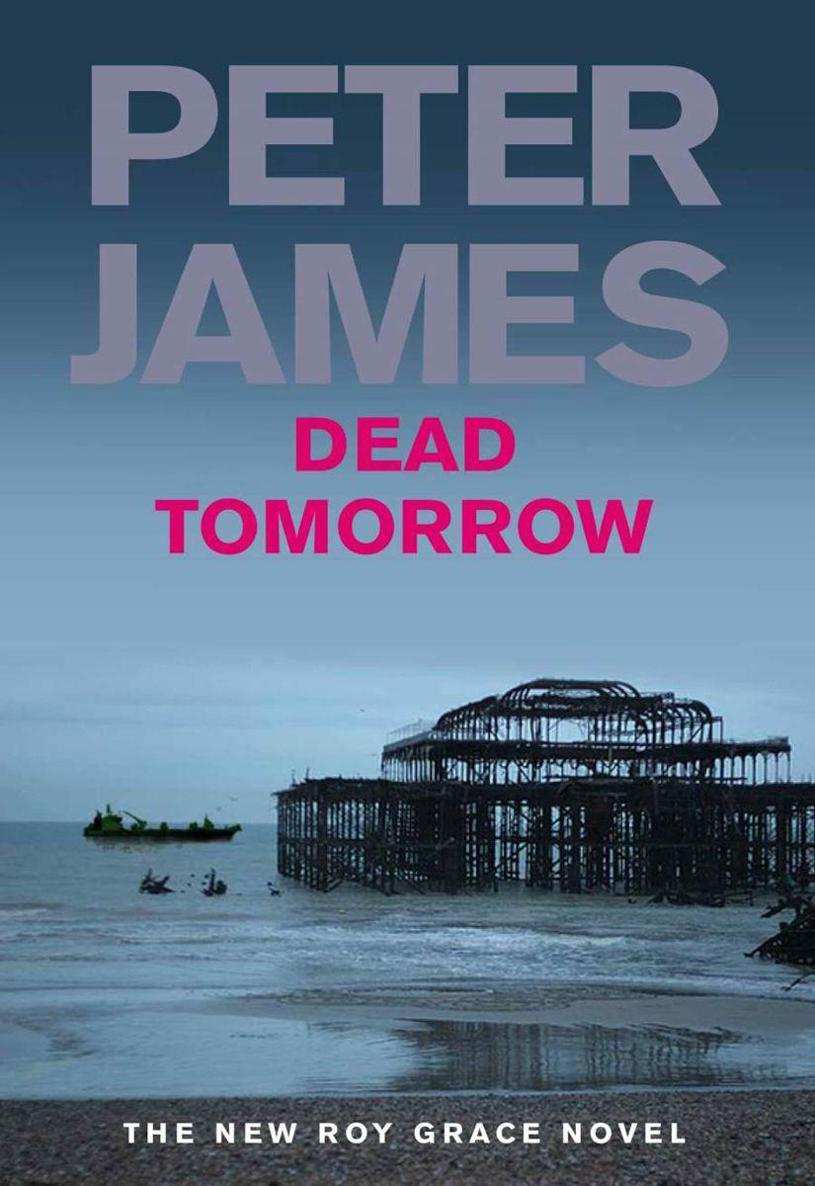

Dead Tomorrow

looked less smart, beside a small white van.

‘Is Ilinca here?’ Rares asked.

Cosmescu turned his head. ‘She’s here, waiting for you. You just have to have a quick medical and then you will meet her again.’

‘Thank you. You are so kind to me.’

Uncle Vlad Cosmescu turned back in silence. Grigore looked over his shoulder and smiled, revealing several gold teeth.

Rares pressed down on the door handle, but nothing happened. He tried again, feeling a sudden stir of panic. Uncle Vlad climbed out and opened the rear door. Rares stepped out and was then steered by Uncle Vlad up to a white door.

It was opened, as they reached it, by a big slab of a woman in a white medical tunic and white trousers. She had a square, unsmiling face with a flat nose and her black hair was cut short, like a man’s, and gelled back. Her name tag read Draguta . She looked at him with stern, cold eyes, then her tiny, rosebud lips formed the thinnest of smiles. In his native Romanian tongue she said, ‘Welcome, Rares. You had a good journey?’

He nodded.

Flanked by thetwo men, he had no option but to step forward, into a clinical-feeling, white-tiled corridor. It smelled of disinfectant. And he felt a sudden, deep unease.

‘Ilinca?’ he said. ‘Where is she?’

The puzzled look in the woman’s small, dark, hooded eyes instantly deepened his unease.

‘She is here!’ Uncle Vlad said.

‘I want to see her now!’

Rares had lived by his wits on the streets of Bucharest for years. He had learned to read expressions in faces. And he did not like the exchange of glances between this woman and the two men. He turned, ducked under Cosmescu’s arms and ran.

Grigore grabbed the collar of his denim jacket. Rares wriggled free of it, then was felled, unconscious, by a single chop on the back of his neck from Cosmescu.

The woman hoisted his limp body over her shoulders and, followed by the two men, carried him on down the corridor a short distance, then through double doors into the small, pre-op room. She laid him out on a steel trolley.

A young Romanian anaesthetist, Bogdan Barbu, who had graduated five years ago from medical school in Bucharest, on a salary of 3,000 euros a year, was waiting to receive him.

Bogdan had thick black hair, brushed forward into a fringe, and designer stubble. With his tanned, lean features, he could have passed for a tennis pro, or an actor. He already had the syringe, filled with a bolus of Benzodiazepine, prepared. Without needing instructions, he injected the pre-med into the upper arm of the unconscious Rares. It would be enough to keep him out for several more minutes.

Between them, they used thetime to remove all of the young Romanian’s clothes and insert an intravenous cannula in his wrist. They then connected it to a drip-line of Propofol, fed by a pump.

This would ensure that Rares did not regain consciousness–but without causing any harm to his precious internal organs.

In the adjoining room, the main operating theatre of the clinic, an anaesthetized twelve-year-old boy, with a liver so diseased he had only weeks to live, was already being opened up by the junior surgeon, a thirty-eight-year-old Romanian liver transplant specialist, Razvan Ionescu. In his home country, Razvan could take home just under 4,000 euros a year–augmented a little with bribes. Working here, in this clinic, he was taking home more than 200,000. In a few minutes, dressed in green surgical scrubs, with magnifying glasses over his eyes, he would be ready to start removing the boy’s failed liver.

Razvan was assisted by two Romanian nurses, who placed the clamps, and every step was scrutinized, in microscopic detail, by one of the most eminent liver transplant surgeons in the UK.

The first rule of medicine which this surgeon had learned many years ago as a young student was, Do no harm .

In his view at this moment, he was doing no harm.

The Romanian street kid had no life ahead of him. Whether he died today or in five years’ time from drug abuse was of little consequence. But the English teenager who would receive his liver was altogether different. He was a talented musician, he had a promising future ahead of him. Of course, it was not up to doctors to play God, to decide who lived and who died. Nor was it up to them to value one human life over another. But the stark reality was that one of these two young men was doomed.

And he wouldnever admit to anyone that the £50,000, tax-free, deposited

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher