![Devils & Blue Dresses: My Wild Ride as a Rock and Roll Legend]()

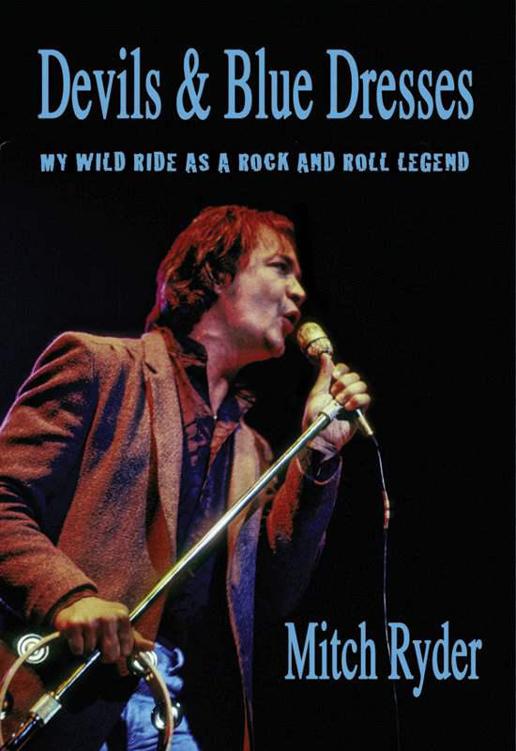

Devils & Blue Dresses: My Wild Ride as a Rock and Roll Legend

I didn’t mean to say that. Damn. I meant to say penis envy has made this country what it is today. Oh, Mommy. Please forgive baby. Baby is sorry. Kiss the boo-boo. Just hold me, you know, deep, like you always do. Flex your “power pac” Mommy. Is it as good for you as it is for me?

Misogynist? I do not think so. No, a misogynist would say something like: “Women, the only animal that can bleed for five days and still not die” or, another old chestnut, “If it wasn’t for that gash between their legs there’d be a bounty on their heads.” Or, and I just love the simplicity of this one, “I treats all my womens good.” One could go on forever. But why? I love women. I love them to a fault. Am I to blame for this dysfunctional existence we call American culture––the early darkening skies of a growing storm that will flatten, and destroy one of the greatest democracies of modern times? Hell no. I’m not to blame

.

Chapter 19

T HESE DAYS WERE FILLED WITH INVITATIONS from the children of wealthy Michigan families. Kim Breach, Bruce Alpert, and a host of young, rich, entranced, want-to-be-star musicians now wanted to be near the famous Mitch Ryder for their own special reasons. I didn’t like cocaine that much, but it was beginning to be the replacement drug of choice for the masses, so I did coke right along with many of them.

FM radio offered me many friendships as well: Dan Carlyle, a young Howard Stern; Arthur Penthallow; Jerry Lubin; and what was referred to as the “X Crew.” That mixture was thrown into the melting pot of my music related “friends” and drug dealers. Now I was starting to do heroin with my good friends Taco and Nancy, who bought the Cinderella Theater with their drug profits, and were trying to legitimize the money in a legal entity. Every other band, now that the major label rush was over, still dreamed of a big contract but the only way left to finance the projects was with the help of local drug dealers. Every facet of the music business in Detroit was in some way or another connected to illegal drug trafficking. Big change was taking foot, though.

Unlike the civil rights movement of the late fifties and early sixties––whose cause was painfully clear, and the message and passion deliberately articulated through powerful leaders––the “counter-culture social revolution” held no treatise, no cohesive strategy and no inflammatory, all-powerful guide. Leadership came from student activists and university intellectuals, problematic gurus, and militant proponents of change whose voices were heard through the burgeoning underground press. The messages, manifestos, and communiqués were sent from places with names like Berkeley and Columbia and even Ann Arbor. Sometimes it was just a letter dropped in a post box.

The SDS (Students for a Democratic Society) began serious recruitment drives in universities, and organized protests became effective enough to warrant a reactionaryresponse by police and the federal government. Borrowing slogans from the civil rights movement, such as “Power to the People” “We Shall Overcome,” or “Death to the Pigs,” the social revolution was turning to a bloody new page. What had begun as a snub to the values of our parents now had the potential for real change, and everyone was lining up on one side or the other.

Blacks seemed to marvel at the media attention given to outraged white youth, compared to the distorted coverage of their own struggle, and began an attempt to draw attention to their programs. This was no longer the American Civil War. This was, in fact, no longer about the war in Vietnam, or the freedom to smoke pot, or have open sex. This was about anarchy. This was the true beginning of insurrection, and the zeal with which young radicals embraced violent confrontations, determined and unafraid, was beautiful to behold. The peace/love romantic, middle-class generation was now, under demand, being asked to put up or shut up. It was as if someone had eaten a bean burrito and decided to ride in your elevator. To quote Ross Perot, there was a “giant sucking sound,” as most everyone fled back to the painfully familiar.

The brutish mind-set of the establishment was not foreign to the city of Detroit. As children, we had heard inspiring stories of conflict as union organizers struggled against the automobile companies. The bloodstained Rouge Overpass in Dearborn at Ford Motor Company, the great labor union

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher