![Easy Prey]()

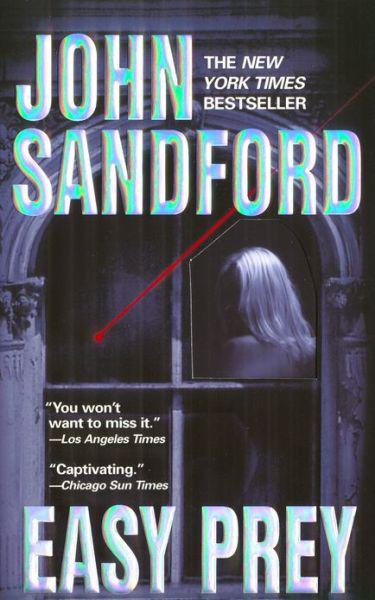

Easy Prey

the mayor, and then the mayor walked them over to Roux’s office. Roux called Lucas, who went down to her office and stood in the back, with Lester, as the chief explained what was happening with the case.

Both Lynn and Lil Olson were dressed from head to toe in black, Lynn in a black-on-black suit that may have come from Manhattan, and Lil in a black lace dress that dropped over a black silken sheath; she also wore a black hat with a net that fell off the front rim over her eyes; her eyebrows matched the hat, severe dark lines, but her hair was a careful, layered honey-over-white blond, like her daughter’s. Her eyes, when Lucas could see them, were rimmed with red. Alie’e got her looks from her father, Lucas thought—the cheekbones, the complexion, the green eyes. Lynn Olson was a natural blonde, but his hair was going white. In the black suit, he looked like a famous artist.

The friends were dressed in flannel and jeans and corduroy; they were purely Minnesota.

“She was going to be in the movies ,” Alie’e’s mother said, her voice cracking. “We had a project just about set. We were interviewing costars. That was the big step, and now . . .”

Rose Marie was good at dealing with parents: patient, sympathetic. She introduced Lucas and Lester, and outlined how the case would be handled.

Lucas felt a strange disjuncture here: Alie’e’s parents, who were probably in their late forties, looked New York, their black-on-black elegant against their blond hair and fair complexions. The words they used were New York, and even their attitude toward Alie’e was New York: all business. Not only was their daughter dead, so was the Alie’e enterprise.

But the sound of the language was small-town Minnesota: round Scandinavian vowels, “oo” instead of “oh,” “boot” instead of “boat.” And every few sentences, a Minnesota construction would creep out.

Rose Marie was straightforward. She mentioned the relationship with Jael—Lil said, “But that was just a lark, girls . . .”—and the possibility of drugs. The Olsons’ eyes drifted away from Rose Marie’s . . . and as Rose Marie was finishing, the door opened, and a heavyset man stepped in, looked around.

He wore jeans, black boots, and a heavy tan Carhartt jacket, with oil stains on one sleeve. His hair was cut like a farmer’s, shaggy on top but down to the skin over the ears. Lynn Olson stood up and said, “Tom,” and Lil stopped sniffling, her head jerking up. The big man scowled at them, nodded at the people from Burnt River, looked at Lucas, Lester, and then at Rose Marie. “I’m Tom Olson,” he said, “Alie’e’s brother.”

“We were just telling your parents what we’re doing,” Rose Marie said.

“Do you know what you’re doing?” he asked Rose Marie.

“We handle this kind of--”

“You’re dealing with a nest of rattlesnakes,” Olson said. “The best thing you could do is beat all of them with a stick. They are sinners, each and every one. They are involved in drugs, illicit sex, theft, and now murder. They’re all criminals.”

“Tom,” Lil said. “Tom, please.”

“We’re questioning everyone who was with Alie’e in the past day,” Rose Marie said. “We’re very confident--”

Tom Olson shook his head once and looked away from her, at his parents. “So. After twenty-five years of abuse, she comes to this. Dead in Minneapolis. Full of drugs, the radio says, heroin—a short pop, the radio says—whatever that is. Some kind of evil they have a special name for, huh? We didn’t hear about that in Burnt River.”

Lester’s eyes flicked at Lucas, as Lynn Olson stood up and said, “Tom, take it easy, huh?”

Olson squared off to his father and said, “I’m not going to take it easy. I can still remember when we called her Sharon.”

“We need to talk to you,” Lester said to Tom Olson.

“To question me? That’s fine. But I know almost nothing about what she was doing. I had one letter a month.”

“Still . . . we’d like to talk.”

Olson ignored him, turned to his parents, shook a finger at them. “How many times did I tell you this?> How many times did I tell you that you were buying death? You even dress like the devil, in Satan’s clothes. Look at you, you spend more money on one shirt than good people spend on a wardrobe. It’s a sickness, and it has eaten into you . . .”

He was starting to foam, shaking not just his finger but his entire body. Lucas pushed away from

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher