![Empty Mansions]()

Empty Mansions

his second wife, Anna, would not inherit the mansion. His will gave Anna and Huguette until June 1928 to move out. At his death in March 1925, only three more years were left. Anna didn’t need three years. The house was W.A.’s hobby, not hers, built for social standing, in which she had no interest. In less than a year, she and Huguette had moved into an apartment down Fifth Avenue.

“The most remarkable dwelling in the world,” which had taken thirteen years to move from architect’s drawings to becoming the Clark family home, had been occupied for only fourteen years.

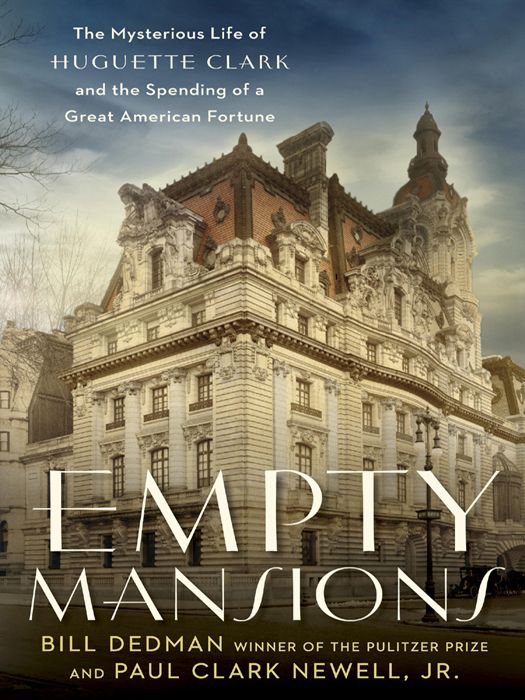

These showgirls on the console of the pipe organ at the Clark mansion were hired by the home’s buyer to lead public tours before the demolition.

( illustration credit5.3 )

Huguette and her half-siblings had trouble, however, finding a buyer for the mansion. Exactly as W.A. had told the property assessor, the Clark mansion was fit for only one owner. It was too expensive to operate, almost too expensive to tear down. Built for $7 million to $10 million, it sold for less than $3 million. The money from the sale was divided among the children.

In the summer of 1927, the tower of the Clark mansion came down, making way for the next wave in architecture, an apartment building with elegant interiors. Other mansions on Fifth Avenue were disappearing as well. The palace of Vincent Astor, the château of Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt—many mansions yielded to modernity. The Gilded Age was past.

At auction, the Clark heirs sold a silver candelabra, hundreds of yards of red velvet wall hangings, porcelain soup plates with gold trim and the Clark crest—nearly half a million dollars in furnishings, or in today’s values more than $6 million. A collector took the bronze carriage gatesto his farm. W.A.’s daughter May moved the walls of two entire rooms to her mansion on Long Island. The mirror-paneled walls and doors went to the city’s children’s hospital. When no buyer was found for the grand marble staircase, it was loaded onto a scow and dumped at sea.

The Clark mansion’s marble staircase, made of creamy, ivory-tinted Maryland marble, lasted only sixteen years.

( illustration credit5.4 )

Before the pinch bars and hammers began the demolition, the new owner of the Clark mansion allowed curiosity seekers inside to gawk at its bones, stripped of its art collection and furnishings. Among more than sixteen thousand tourists paying fifty cents for a peek was Charlie Chaplin. To promote the tours, showgirls posed for photographs: eight showgirls standing in front of the dining room fireplace, then the same eight clowning on the pipe organ.

Ah, the pipe organ.No one thought to auction off Anna and W.A.’s $120,000 marvel. The real estate developer asked the man handling the demolition if he could take it home, thinking the organ might look good in his home or his church. He was prepared to pay a few thousand dollars, but the wrecker told him, “You can have the organ, if you’ll give me a cigar.” The developer soon realized his folly. The pipe organ was too inextricably built into the walls of the house to be removed intact. It was dumped to fill a swamp in Queens. He had wasted a perfectly good cigar.

NEW YORK’S DISAPPEARING MILLIONAIRES’ ROW

Prominent residences on Fifth Avenue in 1914, shown as a walking tour from south to north. Dates indicate the life span of each building.

1. William H. Vanderbilt. 1881–1942.

Replaced by commercial buildings

.

2. Morton Plant. 1905–.

Cartier since 1917

.

3. William Kissam Vanderbilt. 1882–1926.

Replaced by a commercial building

.

4. Cornelius Vanderbilt II. 1882–1927.

Replaced by Bergdorf Goodman

.

5. Elbridge Gerry. 1897–1929.

Replaced by the Pierre hotel

.

6. Caroline Astor, son John Jacob Astor IV. 1896–1926.

Replaced by Temple Emanu-El

.

7. George J. Gould. 1908–1961.

Replaced by apartments

.

8. William C. Whitney. 1884–1942.

Replaced by apartments

.

9. Henry Clay Frick. 1914–.

The Frick Collection since 1935

.

10. Edward S. Harkness. 1908–.

The Commonwealth Fund since 1952

.

11. W. A. Clark. 1911–1927.

Replaced by an apartment building

.

12. James B. Duke. 1912–.

New York University Institute of Fine Arts since 1957

.

13. Harry Payne Whitney. 1906–.

Cultural Services of the French Embassy since 1952

.

14. Isaac D. Fletcher. 1899–.

Ukrainian Institute of America since 1955

.

15. Benjamin N. Duke. 1901–.

Owned by Mexican billionaire Carlos

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher