![Empty Mansions]()

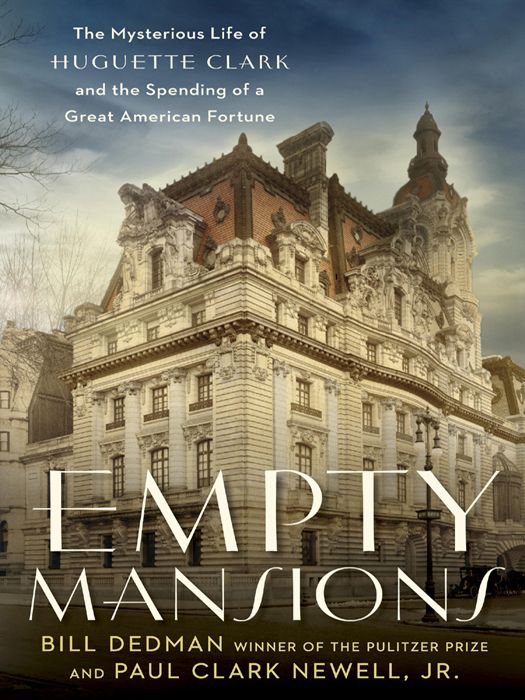

Empty Mansions

birthday.

Another of the artists, J. P. Pinchon, summed up his relationship with the American heiress. He wrote to Huguette in 1953, accepting in his eighties a new commission, even as he recognized he was near death. “The fairy tale continues, and you make my life beautiful. At the beginning of our acquaintance, I compared you to a good fairy who made the dream of any artist at the end of his career come true. Your magic wand never stopped, and I work with joy.”

These artists never knew what their good fairy looked like. The Lorioux family sent photos to Huguette but never received any in return.They knew only her telegrams and her high voice, asHuguette would call to inquire about the illustrator’s grandchildren.The Lorioux family had invited Huguette to France many times, but she always begged off. No, she said, she wouldn’t be able to return there. They asked why. She explained: the French Revolution.

Huguette said she was afraid she might be kidnapped or killed if there were another revolution, sounding as if a guillotine were always ready for the highborn. After all, to the long-lived Huguette, the French Revolution was only a little more than one lifetime before her birth.

ANDREE’S COTTAGE

E NCHANTED FOR MOST of the twentieth century by the mystery of the Clark summer estate hidden on a hill, the residents of Santa Barbara created their own legends of Bellosguardo. One day in 1986, Huguette’s California attorney sent to her New York attorneya detailed report of misinformation spread as a new trolley bus for tourists made its daily run past East Beach toward Montecito. The tour guide explained over the loudspeaker that the Clarks were the owners of the Anaconda Copper Company. (False.) The Clarks didn’t think they were going to be able to have children. (False.) So they adopted a French orphan. (False.) She never married. (False.) And the daughter maintains a home in Paris. (False.)

Huguette’s New York attorney discussed with her what action to take to correct these falsehoods. None, she said. Wanting to maintain her privacy at all costs, she agreed that they wouldn’t make a fuss. Still, from time to time, the California attorney sent his secretary to ride the Montecito trolley, just to monitor the tour guides.

Though the details were all wrong, the legend of Bellosguardo was, in essence, true. The mansion had been frozen in Huguette’s memory, unchanged since the Truman administration. It was the most important place to Huguette, her mother’s place.

The name Bellosguardo (“beautiful lookout,” pronounced BELL-os-GWAR-doe) was attached to the coastal estate on this oceanfront mesa by the Oklahoma oilman William Miller Graham and his wife, Lee Eleanor Graham, who built a 25,000-square-foot Italian villa there in 1903. One party thrown by the theatrical Mrs. Graham included a psychic, a juggler, and a trained monkey. The estate was used several times as a film set during the silent film era, serving as a Roman emperor’s palace for the 1913 one-reeler

In the Days of Trajan

.

After a divorce and bankruptcy put Lee Eleanor Graham into a house-poor situation, she leased Bellosguardo to Frederick W. Vanderbilt, grandson of the Commodore. The next summertime tenants wereAnna, W.A., and their seventeen-year-old daughter, Huguette. The copper king’s family liked the house so much that in December 1923, W.A. offered Mrs. Graham $300,000 cash for it, adding, “Take it or leave it.” W.A. had only a year and a few months to enjoy this acquisition before his death. Bellosguardo would be Anna’s mansion, not his.

In 1933, eight years after the Santa Barbara earthquake and five years after Huguette’s wedding there, Anna began to have the old Graham home razed. It had been too severely damaged by the earthquake, and Anna wanted something more quakeproof—a home built of reinforced concrete and sheathed in granite, with walls sixteen inches thick.

She also wanted something more French. The architectural style is late-eighteenth-century French with Georgian influences, a formal style somewhat unusual for an oceanfront setting in California. It was designed by the renowned architect Reginald Johnson, who had designed the Santa Barbara Biltmore. After Anna allowed extensive archaeological explorations of the site, the house was completed in 1936, with twenty-seven rooms and 23,000 square feet, or about twice the size of Jefferson’s Monticello. The building permit estimated the cost

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher