![Empty Mansions]()

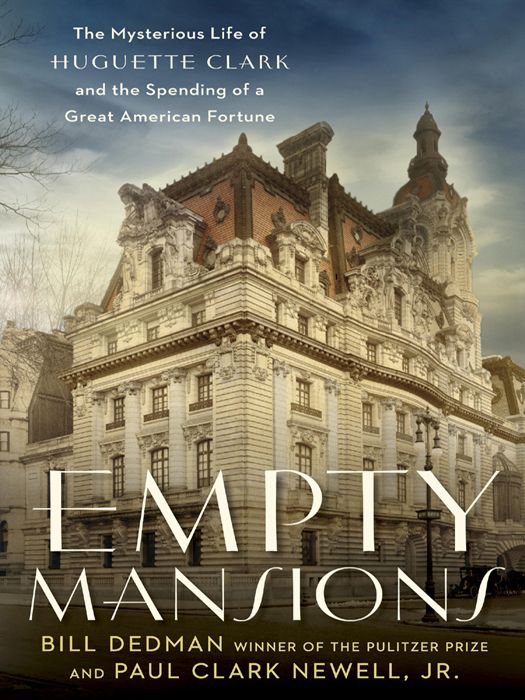

Empty Mansions

silhouette of an American ship near the shore. Anna grew suspicious of outsiders and at one point mistook a kelp cutter boat for a Japanese submarine.

Because of the ever-present danger of invasion, Anna sought a refuge away from the coast for herself and Huguette, and, more important, for the staff.She bought a 215-acre ranch in the Santa Ynez Valley, twenty-two miles northwest of Santa Barbara. CalledRancho Alegre (“cheerful ranch”), it included a ranch house, a sloping meadow for horses and deer, a swimming pool fed by a mountain stream, and open views of Figueroa Mountain. Guests at the Clark ranch could ride horses, including a recalcitrant brown stallion named Don Antonio and the pure white Lady, who had been known in town as a flag bearer in parades.

Although the Japanese surrendered after the United States dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, the closed-off feeling never left Bellosguardo. Anna was rattled when one night the electricity failed, leaving the entire estate in the dark. After that episode, whenever Anna and Huguette planned a visit of only a week or two, they would sleep at the Biltmore, saying they didn’t want to trouble the staff to open up the house.

Anna was getting older, and may have wearied of the long train rides. Anna and Huguette made their last trip west sometime around 1953.

While the Chrysler convertible and the Cadillac limousine stayed in the garage, Anna gave the Rolls-Royce to the chauffeur, Armstrong, who hadn’t used it in quite a while, except to have fun by putting on his white gloves for picking up an embarrassed Barry Hoelscher, the estate manager’s son, after classes at Santa Barbara High School.

FIRST-CLASS CONDITION

A FTER A NNA DIED in 1963, leaving Bellosguardo and Rancho Alegre to Huguette, the daughter issued new instructions to the staff. No longer was the house to be kept in readiness for the arrival of the Clarks under a forty-eight-hour rule.

When John Douglas came on as estate manager in 1983 after Albert Hoelscher died, he was given only two instructions: Keep everything in “first-class condition” and in “as original condition as possible.”

When El Niño storms uprooted a half dozen hundred-foot trees at Bellosguardo in the 1980s, the gardeners planted replacements and sent photos to New York. Huguette sent word that one of the new trees wouldn’t do; it was too small. The tree was taken out, and a mature tree was planted. She declared that tree also too small. Finally, on the third try, she said it would have to do.

When painters finished work on the back of the service wing, Douglas sent photos of the work to New York. He received a quick reply, through Huguette’s attorney. The painting was fine, but “Mrs. Clark would like to know what happened to the doghouse that the Pekingese used.” The Pekingese had died many years earlier. Douglas asked if Mrs. Clark wanted the doghouse in place even if there was no dog. Her attorney responded that Mrs. Clark was well aware that the dog was no longer there but wanted to be sure its house was still on the property. It was.

Huguette insisted that an archway leading through a dense hedge of Monterey cypress be kept just as she remembered it. She sent word after seeing a photo that she “would like to know if the small oak tree that was outside her bedroom window could be replanted.”

One Clark relative recalled being shocked, on a rare visit to the main house, when a housekeeper barked, “Who moved that chair?” The housekeeper moved it about four feet back to its spot.

Her mother was gone, and Huguette would have to live with that, but her mother’s house could be preserved indefinitely.

• • •

Not even for kings would Huguette allow Bellosguardo to be disturbed.

She turned down the entreaties of an agent for Mohammad Reza Pahlavi,the shah of Iran, when he wanted to buy the property in January 1979, in the last days before he fled the Islamic Revolution. Even after his death, the shah, the last king of Iran, couldn’t meet the admission standards for the Montecito neighborhood. His sister wrote to the Santa Barbara Cemetery asking to buy space for a family mausoleum but was refused.

Huguette wouldn’t give permission for the Hollywood billionaire Marvin Davis to land his helicopter for a tour of Bellosguardo in 1989, when he was offering $30 million to $40 million for the estate.

Newspapers offered reports that the Beanie Babies tycoon, Ty

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher