![Fatherland]()

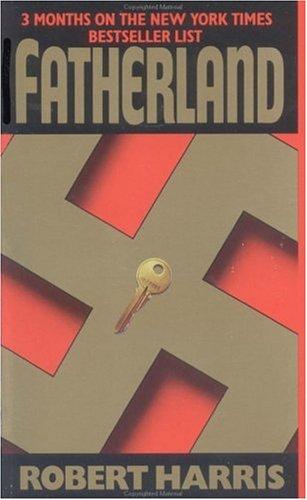

Fatherland

thousand frozen needles. On the Potsdamer-Chaussee, the spray from the wheels of the passing ears forced the few pedestrians close to the sides of the buildings. Watching them through the rain-flecked window, March imagined a city of blind men, feeling their way to work.

It was all so normal Later, that was what would strike him most. It was like having an accident: before it, nothing out of the ordinary; then, the moment; and after it, a world that was changed forever. For there was nothing more routine than a body fished out of the Havel. It happened twice a month—derelicts and failed businessmen, reckless kids and lovelorn teenagers; accidents and suicides and murders; the desperate, the foolish, the sad.

The telephone had rung in his apartment in Ansbacher-Strasse shortly after 6:15. The call had not awakened him. He had been lying in the semidarkness with his eyes open, listening to the rain. For the past few months he had slept badly.

"March? We've got a report of a body in the Havel." It was Krause, the Kripo's night duty officer. "Go and take a look, there's a good fellow."

March had said he was not interested.

"Your interest or lack of it is beside the point."

"I am not interested," March had said, "because I am not on duty. I was on duty last week, and the week before." And the week before that , he might have added. "This is my day off. Look at your list again."

There had been a pause at the other end, then Krause had come back on the line, grudgingly apologetic. "You're in luck, March. I was looking at last week's rota. You can go back to sleep. Or—" he had sniggered "—whatever else it was you were doing."

A gust of wind had slashed rain against the window, rattling the pane.

There was a standard procedure when a body was discovered: a pathologist, a police photographer and an investigator had to attend the scene at once. The investigators worked off a rota kept at Kripo headquarters in Werderscher-Markt.

"Who's on 'today, as a matter of interest?"

"Max Jaeger."

Jaeger. March shared an office with Jaeger. He had looked at his alarm clock and thought of the little house in Pankow where Max lived with his wife and four daughters: during the week, breakfast was just about the only time he saw them. March, on the other hand, was divorced and lived alone. He had set aside the afternoon to spend with his son. But the long hours of the morning stretched ahead, a blank. The way he felt, it would be good to have something routine to distract him.

"Oh, leave him in peace," he had said. "I'm awake. I'll take it."

That had been nearly two hours ago. March glanced at his passenger in the rearview mirror. Jost had been silent ever since they had left the Havel. He sat stiffly in the backseat, staring at the gray buildings slipping by.

At the Brandenburg Gate, a policeman on a motorcycle flagged them to a halt.

In the middle of Pariser-Platz, an SA band in sodden brown uniforms wheeled and stamped in the puddles. Through the closed windows of the Volkswagen came the muffled thump of drums and trumpets pounding out an old Party marching song. Several dozen people had gathered outside the Academy of Arts to watch them, shoulders hunched against the rain.

It was impossible to drive across Berlin at this time of year without encountering a similar rehearsal. In six days' time it would be Adolf Hitler's birthday—the Führertag , a public holiday—and every band in the Reich would be on parade. The windshield wipers beat time like a metronome.

"Here we see the final proof," murmured March, watching the crowd, "that in the face of martial music, the German people are mad ."

He turned to Jost, who gave a thin smile.

A clash of cymbals ended the tune. There was a patter of damp applause. The bandmaster turned and bowed. Behind him, the SA men had already begun half walking, half running back to their bus. The motorcycle cop waited until the Platz was clear, then blew a short blast on his whistle. With a white-gloved hand he waved them through the gate.

Unter den Linden gaped ahead of them. It had lost its lime trees in '36—cut down in an act of official vandalism at the time of the Berlin Olympics. In their place, on either side of the boulevard, the city's Gauleiter, Josef Goebbels, had erected an avenue of ten-meter-high stone columns, on each of which perched a Party eagle, wings outstretched. Water dripped from their beaks and wingtips. It was like driving through a Red Indian burial

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher