![Fatherland]()

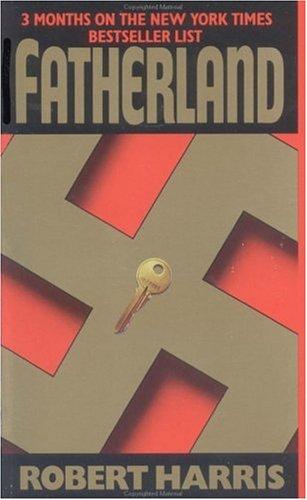

Fatherland

from for seven, who had just denounced you to the authorities? "She's not like you" was all he could think to say.

"Meaning?"

"She doesn't have ideas of her own. She's concerned about what people think. She has no curiosity. She's bitter."

"About you?"

"Naturally."

"Is she seeing anyone else?"

"Yes. A Party bureaucrat. Much more suitable than me."

"And you? Do you have anyone?"

A klaxon sounded in March's mind. Dive, dive, dive . He had had two affairs since his divorce. A teacher who had lived in the apartment beneath his, and a young widow who taught history at the university—another friend of Rudi Halder's: he sometimes suspected Rudi had made it his mission in life to find him a new wife. The liaisons had drifted on for a few months, until both women had tired of the last-minute calls from Werderscher-Markt: "Something's come up, I'm sorry . . ."

Instead of answering her, March said, "So many questions. You should have been a detective."

She made a face at him. "So few answers. You should have been a reporter."

The waiter poured more wine. After he had moved away, she said, "You know, when I met you, I hated you on sight."

"Ah. The uniform. It blots out the man."

"That uniform does. When I looked for you on the plane this afternoon I barely recognized you."

It occurred to March that here was another reason for his good mood: he had not caught a glimpse of his black silhouette in a mirror, had not seen people shrinking away at his approach.

"Tell me," he said, "what do they say about the SS in America?"

She rolled her eyes. "Oh, come on, March. Please. Don't let's ruin a good evening."

"I mean it. I'd like to know." He had to coax her into answering.

"Well, murderers," she said eventually. "Sadists. Evil personified. All that. You asked for it. Nothing personal intended, you understand. Any other questions?"

"A million. A lifetime's worth."

"A lifetime! Well, go ahead. I have nothing planned."

He was momentarily dumbfounded, paralyzed by choice. Where to start?

"The war in the East," he said. "In Berlin we hear only of victories. Yet the Wehrmacht has to ship the coffins home from the Urals front at night on special trains, so nobody sees how many dead there are."

"I read somewhere that the Pentagon estimates a hundred thousand Germans killed since 1960. The Luftwaffe is bombing the Russian towns flat day after day, and still they keep coming back at you. You can't win because they don't have anywhere else to go. And you can't use nuclear weapons, in case we retaliate and the world blows up."

"What else?" He tried to think of recent headlines. "Goebbels says German space technology beats the Americans' every time."

"Actually, I think that's true. Peenemünde had satellites in orbit years ahead of ours."

"Is Winston Churchill still alive?"

"Yes. He's an old man now. In Canada. He lives there. So does the queen." She noticed his puzzlement. "Elizabeth claims the English throne from her uncle."

"And the Jews?" said March. "What do the Americans say we did to them?"

She was shaking her head. "Why are you doing this?"

"Please. The truth."

"The truth? How do I know what the truth is?" Suddenly she had raised her voice, was almost shouting. People at the next table were turning around. "We're brought up to think of Germans as something from outer space. Truth doesn't enter into it."

"Very well, then. Give me the propaganda."

She glanced away, exasperated, but then looked back with an intensity that made it difficult for him to meet her eyes. "All right. They say you scoured Europe for every living Jew—men, women, children, babies. They say you shipped them to ghettos in the East, where thousands died of malnutrition and disease. Then you forced the survivors farther east, and nobody knows what happened after that. A handful escaped over the Urals into Russia. I've seen them on TV. Funny old men, most of them a bit crazy. They talk about execution pits, medical experiments, camps that people went into but never came out of. They talk about millions of dead. But then the German ambassador comes along in his smart suit and tells everyone it's all just Communist propaganda. So nobody knows what's true and what isn't. And I'll tell you something else—most people don't care." She sat back in her chair. "Satisfied?"

"I'm sorry."

"So am I." She reached for her cigarettes, then stopped and looked at him again. "That's why you changed your mind at the hotel about bringing me along, isn't

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher