![Fatherland]()

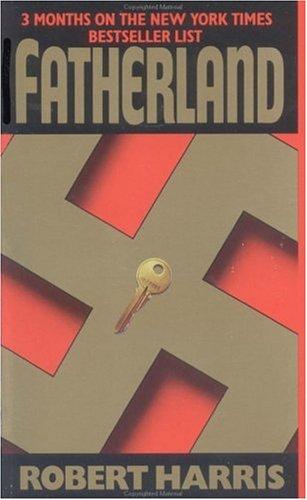

Fatherland

hotel.

Someone tapped softly on the door. A man's voice called his name.

Now what? He strode across the room, flung open the door. A waiter was in the corridor, holding a tray. He looked startled.

"Sorry, sir. With the compliments of the lady in room 277, sir."

"Yes. Of course." March stood aside to let him through. The waiter came in hesitantly, as if he thought March might hit him. He set down the tray, lingered fractionally for a tip and then, when none was forthcoming, left. March locked the door behind him.

On the table was a bottle of Glenfiddich, with a one-word note: "Détente?"

He stood at the window, his tie loosened, sipping the malt whisky, looking out across the Zürichsee. Traceries of yellow lanterns were strung around the black water; on the surface, pinpricks of red, green and white bobbed and winked. He lit yet another cigarette, his millionth of the week.

People were laughing in the drive beneath his window. A light moved across the lake. No Great Hall, no marching bands, no uniforms. For the first time in—what was it?—a year, at least, he was away from the iron and granite of Berlin. So. He held up his glass and studied the pale liquid. There were other lives, other cities.

He noticed, along with the bottle, that she had ordered two glasses.

He sat down on the edge of the bed and looked at the telephone. He drummed his fingers on the little table.

Madness.

She had a habit of thrusting her hands deep into her pockets and standing with her head on one side, half smiling. On the plane, he remembered, she had been wearing a red wool dress with a leather belt. She had good

legs, in black stockings. And when she was angry or amused, which was most of the time, she would flick at the hair behind her ear.

The laughter outside drifted away.

"Where have you been the past twenty years?" Her contemptuous question to him in Stuckart's apartment.

She knew so much. She danced around him.

"The millions of Jews who vanished in the war. . ."

He turned her note over in his fingers, poured himself another drink and lay back on the bed. Ten minutes later he lifted the receiver and spoke to the operator.

"Room 277."

Madness, madness .

They met in the lobby, beneath the fronds of a luxuriant palm. In the opposite corner a string quartet scraped its way through a selection from Die Fledermaus.

March said, "The Scotch is very good."

"A peace offering."

"Accepted. Thank you." He glanced across at the elderly cellist. Her stout legs were held wide apart, as if she were milking a cow. "God knows why I should trust you."

"God knows why I should trust you."

"Ground rules," he said firmly. "One: no more lies. Two: we do what I say, whether you want to or not. Three: you show me what you plan to print, and if I ask you not to write something, you take it out. Agreed?"

"It's a deal." She smiled and offered him her hand. He took it. She had a cool, firm grip. For the first time he noticed she had a man's watch around her wrist.

"What changed your mind?" she asked.

He released her hand. "Are you ready to go out?" She was still wearing the red dress.

"Yes."

"Do you have a notebook?"

She tapped her coat pocket. "Never travel without one."

"Nor do I. Good. Let's go."

Switzerland was a cluster of lights in a great darkness, enemies all around it: Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany north and east. Its survival was a source of wonder: "the Swiss miracle," they called it.

Luxembourg had become Moselland, Alsace-Lorraine was Westmark; Austria was Ostmark. As for Czechoslovakia—that bastard child of Versailles had dwindled to the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. Poland, Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia—vanished from the map. In the East, the German Empire was carved four ways into the Reichskommissariate Ostland, Ukraine, Caucasus, Muscovy.

In the West, twelve nations—Portugal, Spain, France, Ireland, Great Britain, Belgium, Holland, Italy, Denmark, Norway, Sweden and Finland—had been corralled by Germany, under the Treaty of Rome, into a European trading bloc. German was the official second language in all schools. People drove German cars, listened to German radios, watched German televisions, worked in German-owned factories, moaned about the behavior of German tourists in German-dominated holiday resorts, while German teams won every international sporting competition except cricket, which only the English played.

In all this, Switzerland alone was neutral. That had not been

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher