![From the Corner of His Eye]()

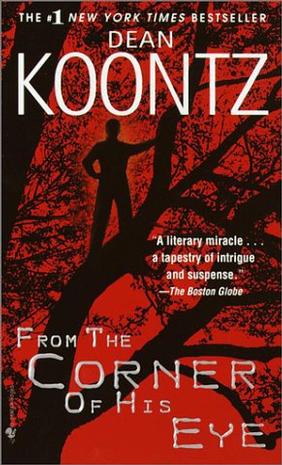

From the Corner of His Eye

hero.

In a magazine article about the hero, passing mention was made of a restaurant where occasionally the great man ate breakfast.

Setting out after dark, Paul had walked south, following the coastal highway. He was accompanied by the windy rush of passing traffic, but later only by the occasional cry of a blue heron, the whisper of a salty breeze in the shore grass, and the murmur of the surf. Without pushing himself too hard, he reached La Jolla by dawn.

The restaurant wasn't fancy. A coffee shop. Aromatic bacon sizzling, eggs frying. The warm cinnamony smell of fresh pastries, the bracing scent of strong coffee. Clean, bright surroundings.

Luck favored Paul: The hero was here, having breakfast. He and two other men were deep in conversation at a comer table.

Paul sat by himself, at the far end of the restaurant from them. He ordered orange juice and waffles.

The short walk across the room, to the hero's table, looked more daunting to Paul than the trek he'd just completed. He was nobody, a small-town pharmacist who missed more work each month, who relied increasingly on his worried employees to cover for him, and who would lose his business if he didn't get a grip on himself. He had never done a great deed, never saved a life. He had no right to impose upon this man, and now he knew he hadn't the nerve to do so, either.

Yet, with no recollection of rising from his chair, he found that he had shouldered his backpack and crossed the room. The three men looked up expectantly.

With every step through the long night walk, Paul had considered what he would say, must say, if this encounter ever took place. Now all his practiced words deserted him.

He opened his mouth but stood mute. Raised his right hand from his side. Worked his fingers in the air, as though the needed words could be strummed from the ether. He felt stupid, foolish.

Evidently, the hero was accustomed to encounters of this nature. He rose, pulled out the unused fourth chair. "Please sit with us."

This graciousness didn't free Paul to speak. Instead, he felt his throat thicken, trapping his voice more tightly still.

He wanted to say: The vain, power-mad politicians who milk cheers from ignorant crowds, the sports stars and preening actors who hear themselves called heroes and never object, they should all wither with shame at the mention of your name. Your vision, your struggle, the years of grueling work, your enduring faith when others doubted, the risk you took with career and reputation-it's one of the great stories of science, and I'd be honored if I could shake your band.

Not a word of that would come to Paul, but his frustrating speechlessness might have been for the best. From everything he knew about this hero, such effusive praise would embarrass him.

Instead, as he settled into the offered chair, he withdrew a picture of Perri from his wallet. It was an old black-and-white school photograph, slightly yellow with age, taken in 1933, the year he'd begun to fall in love with her, when they were both thirteen.

As if he'd been presented with many previous photos under these circumstances, Jonas Salk accepted the picture. "Your daughter?"

Paul shook his head. He presented a second picture of Perri, this one taken on Christmas Day, 1964, less than a month before she died. She lay in her bed in the living room, her body shrunken, but her face so beautiful and alive.

When finally he found his voice, it was rough-sawn with a blade of grief. "My wife. Perri. Perris Jean."

"She's lovely."

"Married

twenty-three years."

"When was she stricken?" Salk asked.

"She was almost fifteen

1935."

"A terrible year for the virus."

Perri had been crippled seventeen years before Jonas Salk's vaccine had spared future generations from the curse of polio.

Paul said, "I wanted you

I don't know

I just wanted you to see her. I wanted to say

to say

"

Words eluded him again, and he surveyed the coffee shop, as if someone might step forward to speak for him. He realized people were staring, and embarrassment drew a tighter knot in his tongue.

"Why don't we take a walk together?" the doctor asked.

"I'm sorry. I interrupted. Made a scene."

"You didn't at all," Dr. Salk assured him. "I need to talk to you. If you would

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher