![Hokkaido Highway Blues]()

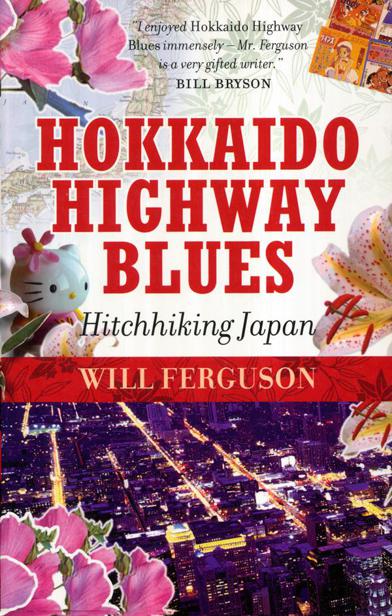

Hokkaido Highway Blues

blue-fume highways.

Akita by night had been exciting. By day, it had all the vitality of a sucked lemon. My teeth were furry. My mouth felt as though I had fallen asleep in a dentist’s chair with the suction tube on at maximum.

I vowed solemnly never to drink again. Or at least, not to excess. Or at least not to the point of falling-down drunk. It was the Law of Diminishing Returns kicking in, the notion that if one ice cream is delicious, eating a hundred ice creams will be a hundred times more so. I had once enjoyed the flurry of festivities but, after riding a wave of drunken parties for over a month, the novelty was fast wearing thin. It had become almost an ordeal. I knew something was wrong that morning in the Love Hotel when I woke up and heard a strange, strangled noise. It was the sound of my liver whimpering. I would have to enter detox after this. My blood was so thin, my heart was pumping pure alcohol. No more, I decided. No more. Well, maybe once more, when I got to Hokkaido, but that was it.

Over breakfast (a cup of coffee and five aspirin), I watched a news report that announced, with barely restrained jubilance, that the Cherry Blossom

Front had finally begun creeping up the coast. The announcer was calling for its arrival in Akita any day, but I was already exhausted with the city and was longing for the open road.

North of Akita City lay Hachirōgata-chōsei, an odd donut-shaped lake. I was fascinated by this. On a map it looked like a giant moat surrounding a vast island. Up close, I discovered, it was simply a manmade lagoon that encircled flat, reclaimed farmland. I was sorely unimpressed.

I followed the eastern edge of this moatlike lagoon, through several drab little towns. Shōwa, Iitagawa, Hachirōgata, Kotōka: there was little to distinguish one from the rest save their names.

I caught a series of short rides from one town to the next. A Coca-Cola delivery man picked me up on the outskirts of Noshiro City and dropped me off ten minutes later, still on the outskirts of Noshiro City. He wanted to know how the rides were in Akita. “Good, eh?” he said, answering his own question. ‘Akita people are famous for their hospitality.”

“Well,” I said. ‘A lot of people slowed down to look—or even to laugh— but they didn’t stop.”

“They are shy,” he explained.

The Coca-Cola man had dropped me off on the Noshiro Perimeter Highway in front of a Kentucky Fried Chicken outlet. I went in and nursed a cup of coffee for as long as I could, before going out and facing the road again. The toilet in the KFC had an electric seat warmer, and that is all I remember of Noshiro City.

Outside, great warheads were boiling over in the sky. My luck held, however, and I caught a ride just before the rains began—big fat raindrops that broke like bullets across the windshield.

“At least it’s not snow,” said the driver, a smiling, awkward young man named Norio Ito. (No relation to the other Itos I had met along the way; Japan has a decidedly limited pool of family names.)

Norio’s car was in utter disarray. There were boxes stacked in the back and flour on everything. There was flour on his chin, powdered in his hair, dusted on the dash. Norio, it turned out, made konnyaku , a word that strikes terror into the hearts of most long-term residents in Japan. Konnyaku— translated, appropriately enough, as “devil’s tongue”—is a gelatinlike substance cooked in slabs, cut into chunks and then hidden in broth and soup as a practical joke, in amid the tofu and boiled eggs. Biting into a chunk of konnyaku is about as appealing and as appetizing as trying to chew on an especially large eraser. It looks like congealed mucous—with flecks of stuff suspended in it, no less—but without the nutritional value or flavor you would expect from mucous.

Though only in his twenties (he looked like he had barely hit his teens), Norio was now in charge of his family business. “My family has always made konnyaku,” he said, though I’m not sure if it was a source of pride or penance. Then, suddenly, “Wait! I have a card. I do. They’re here somewhere.” And he began searching through his glove compartment and among his various flour-dusted boxes and even under the seats, an action that involved putting his head below the dash for extended periods of time while holding the steering wheel on autopilot with his left hand. We were slowly drifting across the center lane when he popped

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher