![Hot Ice]()

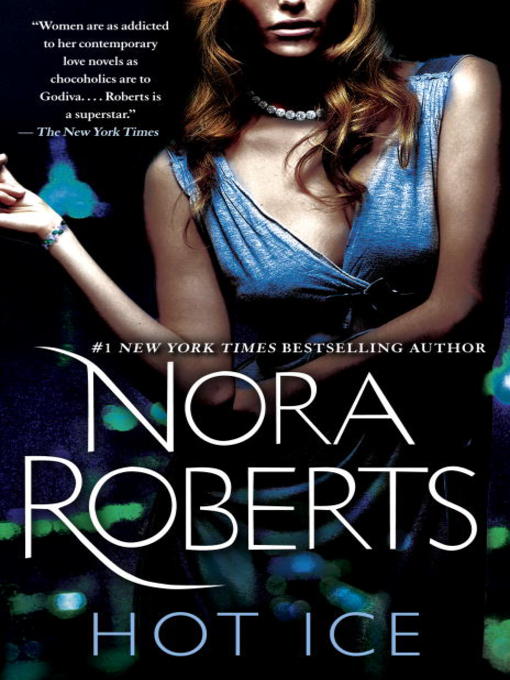

Hot Ice

Whitney had lain awake for some time, going over the journey. In many ways it had been a lark, an exciting, somewhat twisted vacation complete with souvenirs and a few exotic meals. If they never found the treasure, she would’ve written it off just that way—except for the memory of a young waiter who’d died only because he’d been there.

Some people are born with a certain comfortable naiveté that never leaves them, mainly because their lives remain comfortable. Money can provoke cynicism or cushion it.

Perhaps her wealth had sheltered her to some extent, but Whitney had never been naive. She counted her change not because she had to worry about pennies, but because she expected value for value. She accepted compliments with grace, and a grain of salt. And she knew to some, life was cheap.

Death could be a means to an end, something accomplished for revenge, for amusement, or for a fee. The fee might vary—the life of a statesman was certainly worth more on the open market than the life of a ghetto drug dealer. One might be worth no more than the price of a syringe full of heroin, the other hundreds of thousands of cool, clean Swiss francs.

A business, some had taken the exchange of life for gain to the height and routine of a brokerage firm. She’d known it before, considered it the way one considered many of the daily social ills. Aloofly. But now she’d dealt with it personally. An innocent man had died, and she might very well have killed a man herself. There was no telling how many other lives had been lost, or bought and sold, in the quest for this particular pot of gold.

Dollars and cents, she mused as she looked down at her neat columns and totals on the notepad. But it had become much more than that. Perhaps like many of the carelessly wealthy, she’d often skimmed over the surface of life without seeing the eddies and currents the less fortunate had to pit themselves against. Perhaps she’d always taken such things as food and shelter for granted until the last few weeks. And perhaps Whitney’s own personal view of right and wrong often depended on circumstances and her own whims. But she had a strong sense of good and bad.

Doug Lord might be a thief, and in his life he might’ve done innumerable things that were wrong by society’s standards. She didn’t give a hang about society’s standards. He was, she’d come to believe, intrinsically good, just as she believed Dimitri was intrinsically bad. She believed it, not naively, but completely, with all the healthy intelligence and instinct she’d been born with.

She’d done something more while the others had slept. Restless, Whitney had finally decided to glance through the books Doug had taken from the Washington library. To pass the time, she’d told herself as she flicked on a flashlight and located the books. As she’d begun to read about the jewels, the gems lost over the centuries, she’d become caught up. The illustrations hadn’t particularly moved her. Diamonds and rubies meant more in three dimensions. But they’d made her think.

Reading through the history of this necklace, that diamond, she’d understood, personally, that what men and women craved for adornment, others had died for. Greed, desire, lust. They were things Whitney could understand, but passions she felt too shallow to die for.

But what of loyalty? Whitney had gone back over the words she’d read in Magdaline’s letter. She’d spoken of her husband’s grief over the queen’s death, but more, his obligation to her. How much had the man Gerald sacrificed for loyalty and what had he kept in a wooden box? The jewels. Had he kept his heritage in a wooden box and mourned a way of life that could never be his again?

Was it money, was it art, was it history? As she’d closed the book she had been left uncertain. Whitney had respected Lady Smythe-Wright, though she’d never quite comprehended her fervor. Now she was dead for little more than having a belief that history, whether it was written in dusty volumes or glittered and shone, belonged to everyone.

Marie had lost her life, along with hundreds of others, with rough justice on the guillotine. People had been driven from their homes, hunted, and slaughtered. Others had starved in the streets. For an ideal? No, Whitney doubted people often died for ideals any more than they truly fought for them. They’d died because they’d been caught up in something that had swept over them and carried them

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher