![Inferno: (Robert Langdon Book 4)]()

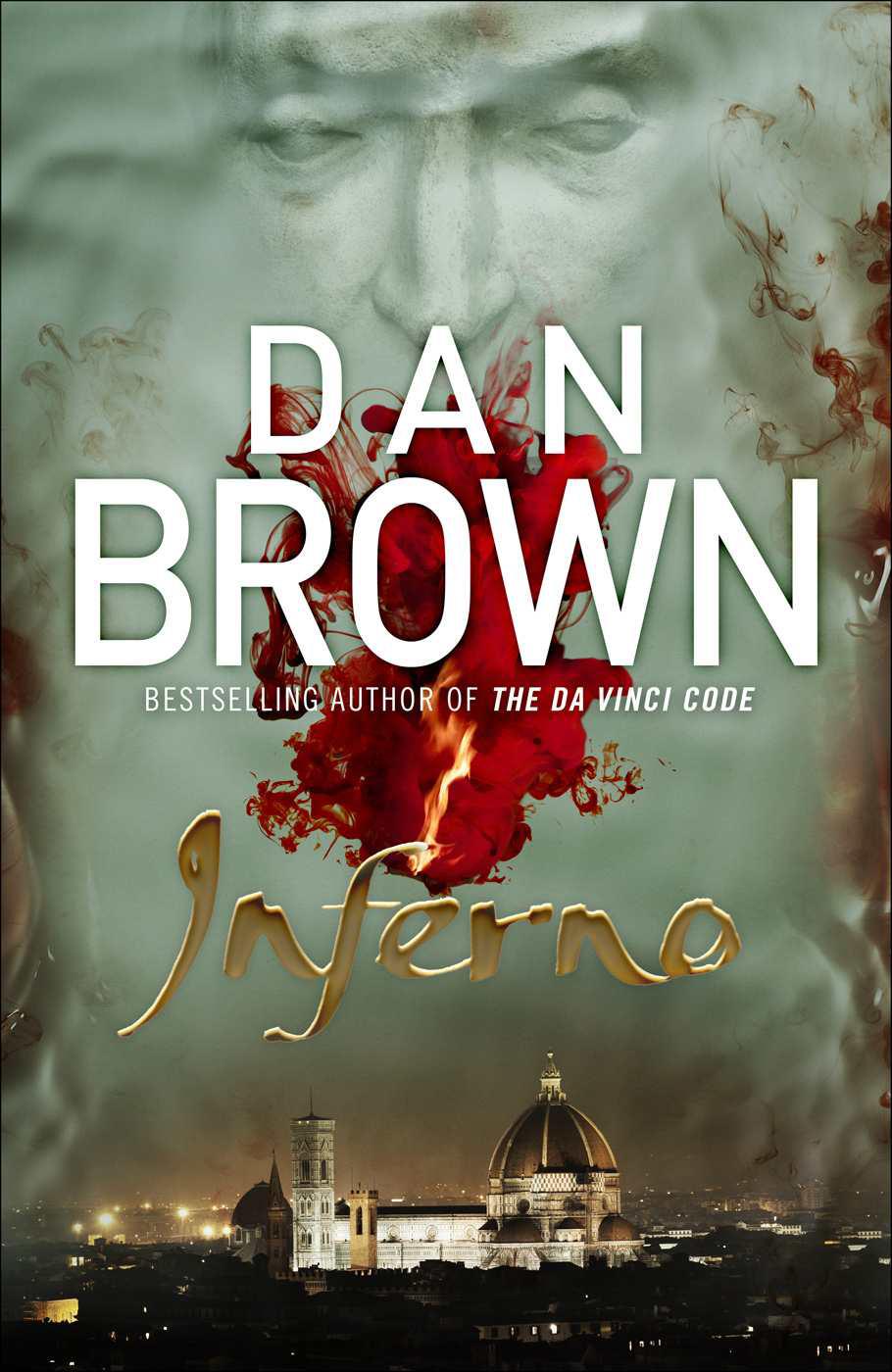

Inferno: (Robert Langdon Book 4)

man’s information, Langdon and his two traveling companions were at this very moment arriving by train. It was too late to summon the local authorities, but the man on the line claimed to know where Langdon was headed.

St. Mark’s Square? Sinskey felt a chill as she imagined the crowds in Venice’s most populated area. “How do you know this?”

“Not on the phone,” the man said. “But you should be aware that Robert Langdon is unwittingly traveling with a very dangerous individual.”

“Who?!” Sinskey demanded.

“One of Zobrist’s closest confidants.” The man sighed heavily. “Someone I trusted. Foolishly, apparently. Someone I believe may now be a severe threat.”

As the private jet headed for Venice’s Marco Polo Airport carryingSinskey and the six soldiers, Sinskey’s thoughts returned to Robert Langdon. He lost his memory? He recalls nothing? The strange news, while explaining several things, made Sinskey feel even worse than she already did about involving the distinguished academic in this crisis.

I left him no choice.

Almost two days ago, when Sinskey recruited Langdon, she hadn’t even let him go back to his house for his passport. Instead, she had arranged for his quiet passage through the Florence Airport as a special liaison to the World Health Organization.

As the C-130 lumbered into the air and pointed east across the Atlantic, Sinskey had glanced at Langdon beside her and noticed he did not look well. He was staring intently at the sidewall of the windowless hull.

“Professor, you do realize this plane has no windows? Until recently, it was used as a military transport.”

Langdon turned, his face ashen. “Yes, I noticed that the moment I stepped aboard. I’m not so good in enclosed spaces.”

“So you’re pretending to look out an imaginary window?”

He gave a sheepish smile. “Something like that, yes.”

“Well, look at this instead.” She pulled out a photo of her lanky, green-eyed nemesis and laid it in front of him. “This is Bertrand Zobrist.”

Sinskey had already told Langdon about her confrontation with Zobrist at the Council on Foreign Relations, the man’s passion for the Population Apocalypse Equation, his widely circulated comments about the global benefits of the Black Plague, and, most ominously, his total disappearance from sight over the past year.

“How does someone that prominent stay hidden for so long?” Langdon asked.

“He had a lot of help. Professional help. Maybe even a foreign government.”

“What government would condone the creation of a plague?”

“The same governments that try to obtain nuclear warheads on the black market. Don’t forget that an effective plague is the ultimate biochemical weapon, and it’s worth a fortune. Zobrist easily could have lied to his partners and assured them his creation had a limited range. Zobrist would be the only one who had any idea what his creation actually did.”

Langdon fell silent.

“In any case,” Sinskey continued, “if not for power or money, those helping Zobrist could have helped because they shared his ideology . Zobrist has no shortage of disciples who would do anything for him. Hewas quite a celebrity. In fact, he gave a speech at your university not long ago.”

“At Harvard?”

Sinskey took out a pen and wrote on the border of Zobrist’s photo—the letter H followed by a plus sign. “You’re good with symbols,” she said. “Do you recognize this one?”

H+

“H-plus,” Langdon whispered, nodding vaguely. “Sure, a few summers ago it was posted all over campus. I assumed it was some kind of chemistry conference.”

Sinskey chuckled. “No, those were signs for the 2010 ‘Humanity-plus’ Summit—one of the largest Transhumanism gatherings ever. H-plus is the symbol of the Transhumanist movement.”

Langdon cocked his head, as if trying to place the term.

“Transhumanism,” Sinskey said, “is an intellectual movement, a philosophy of sorts, and it’s quickly taking root in the scientific community. It essentially states that humans should use technology to transcend the weaknesses inherent in our human bodies. In other words, the next step in human evolution should be that we begin biologically engineering ourselves .”

“Sounds ominous,” Langdon said.

“Like all change, it’s just a matter of degree. Technically, we’ve been engineering ourselves for years now—developing vaccines that make children immune to certain diseases …

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher