![Kushiel's Dart]()

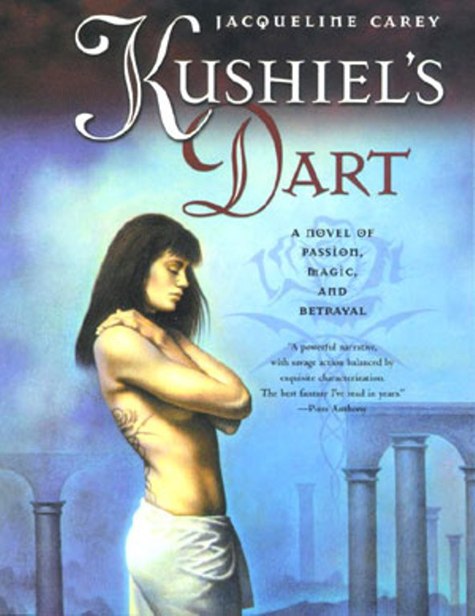

Kushiel's Dart

churning snow in their terror, but he floundered in our wake, making a horrid squeal of fear, his hindquarters inches away from swiping claws the length of my whole hand. I have heard the fabled oliphaunts of Bhodistan are the largest creatures living, but if I never see a doughtier beast than a Skaldic bear, I will rest well content. In this one thing, winter proved our friend, for the bear gave up the chase after a short distance and turned to lumber back into the depths of its shelter, and sleep.

Thus did we reach the CamaelineRange without further incident.

There is no easy way to cross from the Skaldic territories into Terre d'Ange. Where the Camaelines give way in the north, the RhenusRiver takes over, too deep and fast to be forded, and seldom bridged since the days of the Tiberian Empire. They, with their legions of engineers, could muster a bridge-building brigade in a matter of a day, given sufficient timber. Since then, D'Angelines have held the river border.

If we dared, I would have ridden clear up to the flatlands and begged passage through Azzalle, for I've no doubt there were loyal adherents to the Crown there, if only in the person of Ghislain de Somerville, who, to the best of my knowledge, still held command of Trevalion. But to cross the heart of Skaldi wilderness was one thing; to ride the borders during wartime-albeit a war Terre d'Ange didn't know was coming-was another. No, it had to be the mountains, and expedience demanded that we attempt the southernmost of the Great Passes.

We rode in the shadow of the tall peaks of the Camaelines for a day, and camped beneath them at night. The snow was deeper here, and it was hard going. Still, we were close enough to sense that the air of home lay on the far side of those cruel mountains, and it gave us heart.

In the morning, we came upon a sight that dashed our hopes.

I had feared that Selig would take further measures against us, and my fears were well-founded. Joscelin, heeding them, made a reconaissance on foot and returned grim-faced, leading me to a secure vantage point. On the snowy plains before the southern pass, we saw them: A party of some two-score Marsi raiders, encamped between us and the pass.

Harald had said he'd traded places with one of Selig's hand-picked thanes. I saw now what he meant. Selig had sent the steading-riders as well, turning out the Marsi tribe to guard the passes against us.

I looked once, hoping against hope, at Joscelin.

"Not a chance," he said ruefully, shaking his head. "There are too many and on open ground, Phedre. I'd be slaughtered."

"What, then?"

He met my eyes reluctantly, then turned, gazing up at the vast mountain peaks, towering high above us.

"No," I said. "Joscelin, I can't."

"We have to," he said gently. "There's no other way."

On the plain below us, the Skaldi of the Marsi built up their fires, singing and holding games, drinking and shouting and dashing at each other in mock combat. For all of that, they kept scouts posted, watching the horizons. There were probably men of Gunter's steading among them, I thought; men I'd known, men I'd served mead. We could hear them, occasionally, the clear thin air carrying their shouts. If word of what we'd done to Selig's thanes had reached them, they'd kill us without blinking. We couldn't go through them, and we couldn't go around them.

He was right. There was no other way.

I pulled my wolfskin cloak tight around me and shivered. "Then let's go. And may Elua have mercy on us."

I will not tell every step of that treacherous journey. It is enough to say that we survived it. Joscelin rode back the way we'd come, flogging his poor mount, and returned in the lowering orange light of sunset to report that he'd found a trail, a mere goat-track, winding up among the crags beyond where the eye could follow. Turning our backs on the Skaldi, we rode back to make camp in the foothills, daring only the smallest of fires. Joscelin fed it all night with twigs, and I daresay it would have fit within his cupped hands. It kept the warmth of life in our flesh, though barely.

In the morning, we began to ascend.

After a certain point, it was no longer possible to ride, and we needs must dismount and climb, using frigid hands and feet to find holds, leading the horses scrambling after. I lost my mount on the first day. It was a horrible thing, and I do not like to think on it; he sheered away from a crag when it loosed a small avalanche of snow and lost his footing.

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher