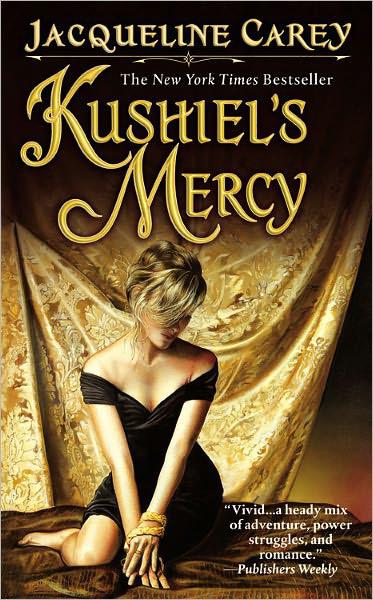

![Kushiel's Mercy]()

Kushiel's Mercy

Sidonie’s voice, bemused. Her hips rose to meet mine, nails digging into my buttocks, urging me deeper.

Alais’ voice in my memory.

I think she’s going to need you very badly one day.

“No,” I repeated, saying it to the Priest of Elua who had uttered that long-ago prophecy, saying it to Alais with her dreams and dire forebodings. I shook my head, dispelling all their warnings and fears. “No, no, no. I’ll do it. I’ll pay the price. Only don’t leave me.”

“Never,” Sidonie gasped.

“Stay with me?” I pressed.

“Always.” Her back arched; it was a promise, not a signale. “Always.”

Seven

Life continued apace.

Swift, too damnably swift. The bright blaze of autumn’s foliage flared and dimmed.

Leaves turned brown and dry, loosed their moorings. In the mornings, the garden where I practiced the Cassiline discipline, telling the hours, sparkled with hoarfrost. The members of Sidonie’s guard watching me huddled in woolen cloaks.

It was the one time of day I always had a pair of her guards in attendance, the one time of day I was otherwise alone and isolated. It had been Claude de Monluc’s idea, not mine, and Sidonie swore she hadn’t asked it of him. If there were any complaints among the guards, I never heard them. I was glad of their presence.

There hadn’t been any threats, but there was a lingering uneasiness beneath the truce.

During the nights, it was easy to forget. During the days, there were reminders.

One came in the form of a ridiculous suit pushed all the way from the provincial court of Namarre to the Palace Court. I held among the estates of my inheritance the duchy of Barthelme, located in the province of Namarre. The seneschal had reported the suit to me—some incident of a vassal lord, the Baron Le Blanc, claiming I had violated an obscure clause in his charter of tenure that granted him a tithing exemption on Muscat grapes.

As it happened, it was true. The Duc de Barthelme who had signed the charter some three hundred years ago had been possessed of a surpassing fondness for Muscat wine and had waived the customary tithe in favor of an annual keg of the barony’s finest. Generations later, an enterprising successor to the duchy had managed to evade the clause in favor of a monetary tithe, and the clause had eventually been forgotten altogether until Jean Le Blanc uncovered it.

According to my seneschal, the matter had been settled in the provincial court. The bailiff’s ruling had been favorable to Le Blanc. The records were surveyed assiduously, and Barthelme was assessed a fine for a hundred and eleven years’ worth of illegally gathered tithes.

The incident stuck in my mind because it had been a sizable sum, and when I’d told Sidonie, she’d laughed and said it was a good thing she wasn’t in love with me for my wealth. I’d given it no more thought until Sidonie brought it up again.

“You remember your old friend Baron le Blanc?” she said one evening. “He’s back.”

I stared at her. “The fellow with the Muscat? Whatever for?”

We were dining in her chambers. Sidonie shrugged, spearing a piece of roasted capon.

“Lost revenues on a hundred and eleven years’ of tithes.”

“It was a stupid clause,” I said.

“It was,” she agreed. “But that’s not the point. The Namarrese bailiff ruled that since the Barons of Le Blanc collected revenues on a hundred and eleven years’ worth of their finest Muscat in lieu of tithing it, he’s no right to complain. Not unless he’s prepared to deliver a hundred and eleven kegs of Muscat to you. Now he’s demanding a hearing Ex Solium.”

Any D’Angeline peer who felt himself wronged by the regional judiciary had a right to demand a hearing from the throne. It was an old law, but one seldom used for frivolous matters.

I raised my brows. “Is Ysandre going to hear it?”

Sidonie shook her head. “I don’t know how it passed through the Court of Assizes, but it did. He’s hired a persuasive advocate. Even so, they decided it wasn’t worth Mother’s time, so it landed on my plate. I’m to take the hearing as a representative of the throne.”

“A suit brought against me as the Duc de Barthelme,” I observed.

“Mm-hmm.” She tapped her fork idly against the rim of her plate. “Passing odd, is it not?”

“It is,” I agreed. “Will you hear it?”

“Gods, no!” she said fervently. “No, I’m not about to walk into that trap. I pleaded lover’s bias in the matter,

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher