![Kushiel's Mercy]()

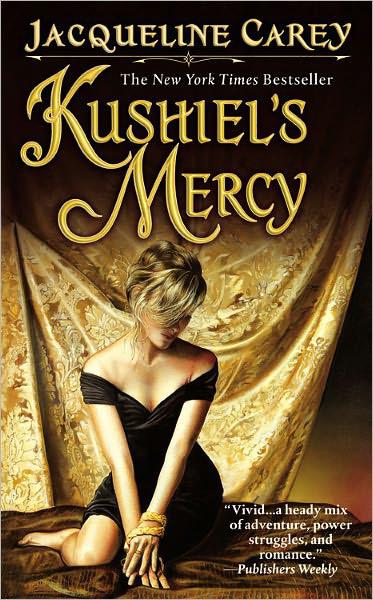

Kushiel's Mercy

had been allowed to walk away from the Guild, but there was a price for that, too.

Silence. Claudia Fulvia had been clear; if I revealed the Guild’s existence and what little I knew of the extent of their vast web, my life—or worse, the lives of my loved ones—was forfeit.

Spies will be spies, Ysandre had said; but I’d seen a measure of their influence in Tiberium. When it suited their purposes, the Guild had provoked a dangerous riot. I remembered Claudia, careless and dismissive . Starting a riot’s one of the easiest things in the world. Even with her warning, I’d gotten caught in it and nearly died. Of course, that was because Bernadette de Trevalion had hired a man to kill me to avenge the death of her brother Baudoin, whom my mother had betrayed—yet another delightful piece of Melisande Shahrizai’s legacy—but it would have been terrifying anyway.

And my comrade Gilot, who had served House Montrève since I was a boy, had died.

Not that night, not then and there, but it was the injuries he sustained in the riot that killed him in the end.

So we kept our silence.

And people began to wonder at my lack of action.

Spring blossomed. A letter came from the Master of the Straits. Hyacinthe wrote with regret that he had found no trace of my mother anywhere on D’Angeline soil. Wherever she was, it was beyond the limits of the gaze of his sea-mirror, which could not see past the lands bounded by the Straits. This news, we did not divulge.

But people began to wonder.

Of her own initiative, Phèdre elected to write once more to old acquaintances and allies among the Stregazza in La Serenissima, pressing them to make one last inquiry into Melisande’s disappearance from the Temple of Asherat there. As a stopgap measure, it wasn’t much, but at least it might serve to provide a viable explanation for any information we did learn without compromising the Guild’s secrecy.

Sidonie’s birthday came and passed; mine fell a few weeks later. The celebrations were muted. After the ugliness of the Longest Night, we’d fallen back into the habit of being circumspect in public. Jean Le Blanc hadn’t been entirely misled. There were a couple members of the Dauphine’s Guard who had been indiscreet, gossiping about what they suspected went on in the bedchamber when they were posted outside her quarters. Claude de Monluc had been furious, had wanted to dismiss them altogether. Sidonie, cool-headed and pragmatic, had refused.

“Gossip’s not a crime,” she observed.

“Lack of loyalty is,” de Monluc said in a grim tone.

“There’s no shame in aught done in love,” Sidonie said, unperturbed. “And no sin in gossiping about it. But matters are tense and I’d sooner be served by men with sense enough not to throw oil on fire. Let them serve in the regular Palace Guard. Give them my thanks and a generous purse. Make the same offer to any who want it.”

Claude obeyed her order.

There were three men who took it; there were thirty who applied for their posts. Young men, mostly, half in love with the notion of our star-crossed romance. They doted on Sidonie, which startled her a bit.

“No one’s ever doted on me before,” she mused.

“You’ve never defied half the realm for the sake of love before,” I said. “And I think they’re beginning to suspect you don’t exactly have ice water running in your veins.”

She laughed. “True.”

The nights . . . Elua, the nights were still wonderful. Knowledge that our time was beginning to dwindle lent a constant sense of urgency. Still, I could feel the tensions at Court rising.

There were moments of respite. In an effort to keep at least half my promise to Alais, I went to Montrève to choose a puppy for her from that spring’s litter. Long ago, I’d given her one of Montrève’s wolfhounds. Alais and the dog had been inseparable, but the dog had been killed at Clunderry, torn open by a swipe of the bear-witch Berlik’s claws.

Sidonie accompanied me, her mother reckoning that having the both of us out of sight for a few weeks might help reduce the sense of unease.

It was strange and wondrous having her there. We rode together, exploring the places I’d loved as a child. I took her to the spring-fed pond hidden in the mountains. I told her about how my cousin Roshana had sought to teach Katherine Friote, the seneschal’s daughter, and me a Kusheline game of courtship, teasing with a quirt of braided grasses.

How I’d been unable to

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher