![Kushiel's Mercy]()

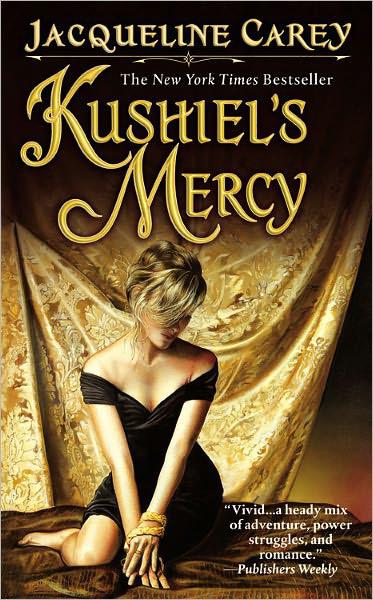

Kushiel's Mercy

hear.

Amarante glanced at me, lips curving. “If it’s what you want, of course.”

Mavros punched me hard in the shoulder. “I hate you,” he said cordially. “Only know that, cousin. I hate you with the blistering heat of a thousand fiery suns.”

The three of us passed the night together; and it was a night impossible to describe, except to say that it was surpassingly beautiful, and when it was over, there was no jealousy left in me. Priests and Priestesses of Naamah are trained in the same arts of pleasure as adepts of the Night Court, but the year of Service they undertake differs.

Afterward, they are free to choose patrons or lovers at will. When Naamah stayed beside Blessed Elua during his wanderings, she gave herself to strangers that he might eat, to the King of Persis that he might be freed. During their year of wandering, Naamah’s acolytes are forbidden to refuse anyone who seeks them out of true longing, that they might better comprehend the sacrifice of the goddess who lay with mortals.

And in turn, Naamah graced them with desire.

I could feel her presence lingering over Amarante like a touch, a claim, and a blessing at once. A mantle of grace lay over us that night: love, desire, and selflessness all intertwined. There were no violent pleasures, only tender ones, but I learned somewhat of myself. I learned I was capable of sharing and being shared, of holding fast and letting go all at once. And I realized I was surpassingly grateful that Amarante had returned, albeit altered. She had long been Sidonie’s closest confidante, her safe harbor. I was glad she would be here while I was gone.

In the morning, Sidonie was thoughtful. “I knew it was time to send you to Naamah,” she said to Amarante. “I didn’t know she would keep so much of you for herself.”

Their eyes met in a manner born of long familiarity, and Amarante smiled. “I held a little back. I’ll always be there when you need me.”

“Soon, I hope,” I said.

She didn’t mistake my meaning. “There’s no word of your mother yet?”

I shook my head. “We’re waiting on word from La Serenissima.”

“I hope it comes soon,” Amarante said quietly.

It did, although it didn’t come from La Serenissima.

It came only a few days later, in the midst of sufficient uproar at Court that it easily passed unnoticed. If tensions in Terre d’Ange were internal and simmering, they were external and rising to a boil elsewhere in the world. Alba’s future remained unsettled.

Queen Ysandre had been unable to broker any lasting peace between Aragonia and the Euskerri, and now fighting had broken out between them in the mountains south of Siovale. Delegates from both nations were beleaguering her—the Aragonians begging her to honor her alliance and stay out of the matter, the Euskerri begging for acknowledgment of their sovereign rights—and the Siovalese lords worried that the fighting would spill across the border.

In the midst of that came the news that a sizable delegation from General Astegal of Carthage—who had thus far done not the slightest thing to justify the rampant unease his appointment had provoked—was lying off the shores of Marsilikos, begging leave to sail up the Aviline River and pay tribute to Queen Ysandre.

And I got a letter.

To all appearances, it was a love-missive, written in a feminine hand, tied with ribbon and scented with perfume. It was delivered to the barracks of the Dauphine’s Guard.

It wasn’t the first of its kind. We’d both gotten them; it was a popular pastime at Court.

This one was unsigned. It contained an innocuous love poem written on thick vellum . . .

but there was a series of subtle notches and lines etched along the edges of the vellum. I fingered them, thinking back on the day in the Temple of Asclepius when the priest had taken my hand and shown me similar notches etched in a clay medallion.

“Who delivered this?” I asked.

Claude de Monluc shrugged. “Some Tsingano lad. He said a lady in Night’s Doorstep paid him.” He grinned. “Not intrigued, are you?”

“Gods, no!” I laughed and showed him the letter. “It’s not signed, that’s all. One never knows if it’s a prank.”

“Like as not it’s just another high-spirited young noblewoman,” he suggested. “Drunk enough to take a dare, sober enough to realize she’d regret it in the morning.”

“Like as not,” I agreed.

Since Sidonie was in conference with her mother, I went

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher