![Kushiel's Mercy]()

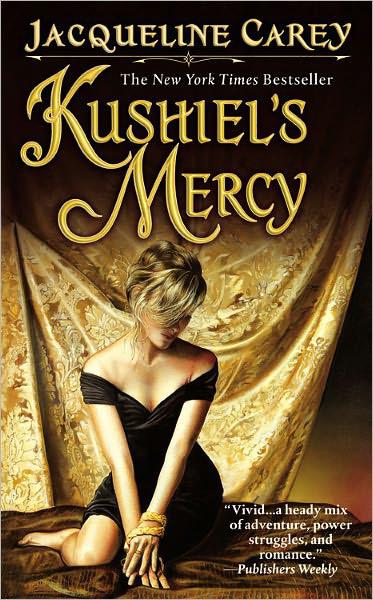

Kushiel's Mercy

disembarked and strolled the docks, getting used to the feeling of solid ground beneath my feet once more. There was a group of sailors dicing in the shadow of a Carthaginian ship.

“Greetings, lads,” I said to them in Hellene. I untied the strings of my purse and fetched out a silver coin. “What’s the news out of Aragonia?”

They glanced up at me with suspicion. “A D’Angeline asks?” one said.

I shrugged. “Not exactly. I’m a long-time exile in the service of the Governor of Cythera.

We’ve got no dog in this fight.”

“General Astegal routed the Aragonian fleet at New Carthage,” the sailor said, putting out his hand. “He’s occupied the city.”

“Huh.” I put the coin in his grimy palm. “Any indication Aragonia means to surrender?”

“Nah.” The sailor shook his head. “Army’s withdrawn to the north. Looks like a long slog.”

“My thanks.” I fished out another coin. “What of Terre d’Ange?”

They exchanged grins. “You have been gone a long while, my lord,” the talkative sailor said. “Don’t know, except the whole country’s damn well flummoxed and at each other’s throats. Meanwhile, Astegal’s pretty little royal bride sits here waiting patiently for him to return.”

They all laughed. I found myself hating them with unexpected intensity.

“Excellent.” I smiled broadly and paid the man his second coin. “Many thanks, my friends.”

He pocketed it. “Don’t mention it.”

By the time I’d strolled back to the ship, Deimos had arranged for my lodgings at an inn the harbor-master had assured him was the most fashionable. He’d hired porters and a palanquin, which I was also given to understand was the most fashionable mode of transport. A very efficient fellow, Captain Deimos.

“Very good,” I said to him. “Where will I find you if I’ve need?”

He jerked his chin at the ship. “We’ll bunk on board until you’ve arranged for proper lodgings and the cargo can be unloaded.”

“Of course.” I fetched a smaller purse out of the inner pocket of my vest and handed it to him. “Make sure your lads have a chance to entertain themselves.”

“We’ve been paid,” Deimos said, but he took it nonetheless. “How long do you reckon we’ll be here?”

I glanced up the hill, past the sprawl of townhouses and multistory apartments, toward the costly villas. “As long as it takes. Does it matter?”

“Not really,” he said. “Just curious.” Deimos lowered his voice. “What exactly is the old ape up to, anyway? He seems deadly serious about it.”

Days at sea, and the man picks a crowded harbor to ask. Gods above, people could be stupid. I gave him my blandest smile. “Spreading goodwill, my lord captain, that Cythera may be left in peace, untouched by any trouble. Happiness is the highest form of wisdom.”

“So I’ve heard,” Deimos said dryly.

I clapped his shoulder. “I’ll send word.”

The porters and the palanquin-bearers were waiting. The latter lowered their poles, allowing me to step lightly into the palanquin. As soon as I was seated, they raised the poles and began moving forward at a smooth, steady trot. The porters followed, carrying my trunks, and a sealed trunk I’d found that bore an engraved plate with Sunjata’s name.

I’d no idea what was in it, but it wasn’t listed on the manifest, and I’d thought it best to take it with me. Some business of her ladyship’s, no doubt.

We passed a sanctuary dedicated to the goddess Tanit, who I understood presided over Carthage along with Ba’al Hammon, and a vast, open space marked by a multitude of carved stelae. One of the porters freed a hand to touch his brow in a gesture of deference.

“What is that place?” I inquired.

“It is the tophet,” he said. “Many children are buried there.” After a moment, he added,

“Not for a very long time. The gods have been merciful.”

What a thought! I couldn’t imagine gods cruel enough to demand such a sacrifice. “Do you have children?” I asked the porter, curious. “Could you offer them if the gods demanded it?”

“I have a son.” He jogged along, holding Sunjata’s trunk balanced atop his head. “To save my people from famine or conquest? If the gods demanded it, yes.”

“I think I’d find a gentler god to worship,” I murmured.

The porter shrugged, or made a gesture that would have been a shrug if he hadn’t been carrying a heavy trunk on his head. “What use is a gentle

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher