![Lamb: the Gospel According to Biff, Christ's Childhood Pal]()

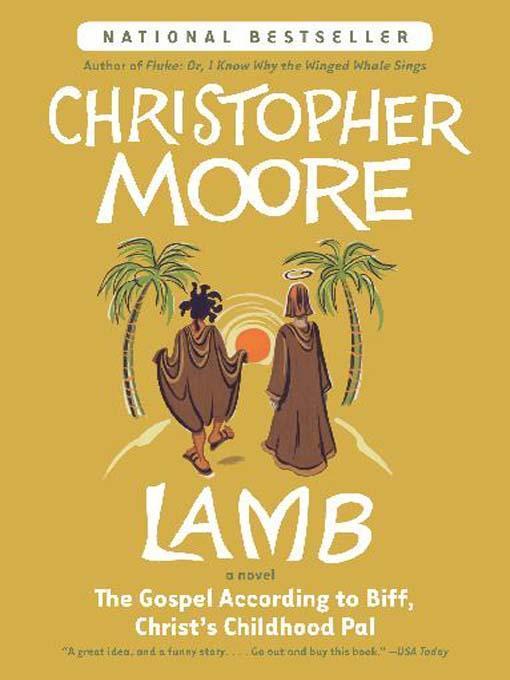

Lamb: the Gospel According to Biff, Christ's Childhood Pal

was a knife in the side.

Joshua put his hand on my forehead.

“I’ll be all right, Josh, you don’t have to do that.”

“Why wouldn’t I?” he said. “Keep your voice down.”

In seconds my pain was gone and I could breathe again. Then I fell asleep or passed out from gratitude, I don’t know which. When I awoke with the dawn Joshua was still kneeling beside me, his hand still pressed against my forehead. He had fallen asleep there.

I carried the combed yak wool to Gaspar, who was chanting in the great cavern temple. It amounted to a fairly large bundle and I set it on the floor behind the monk and backed away.

“Wait,” Gaspar said, holding a single finger in the air. He finished his chant, then turned to me. “Tea,” he said. He led and I followed to the room where he had received Joshua and me when we had first arrived. “Sit,” he said. “Sit, don’t wait.”

I sat and watched him make a charcoal fire in a small stone brazier, using a bow and fire drill to start the flames first in some dried moss, then blowing it onto the charcoal.

“I invented a stick that makes fire instantly,” I said. “I could teach—”

Gaspar glared at me and held up the finger again to poke my words out of the air. “Sit,” he said. “Don’t talk. Don’t wait.”

He heated water in a copper pot until it boiled, then poured it over some tea leaves in an earthenware bowl. He set two small cups on the table, then proceeded to pour tea from the bowl.

“Hey, doofus!” I yelled. “You’re spilling the fucking tea!”

Gaspar smiled and set the bowl down on the table.

“How can I give you tea if your cup is already full?”

“Huh?” I said eloquently. Parables were never my strong suit. If you want to say something, say it. So, of course, Joshua and Buddhists were the perfect people to hang out with, straight talkers that they were.

Gaspar poured himself some tea, then took a deep breath and closed his eyes. After perhaps a whole minute passed, he opened them again. “If you already know everything, then how will I be able to teach you? You must empty your cup before I can give you tea.”

“Why didn’t you say so?” I grabbed my cup, tossed the tea out the same window I’d tossed Gaspar’s stick, then plopped the cup back on the table. “I’m ready,” I said.

“Go to the temple and sit,” Gaspar said.

No tea? He was obviously still not happy about my almost-threat on his life. I backed out of the door bowing (a courtesy Joy had taught me).

“One more thing,” Gaspar said. I stopped and waited. “Number Seven said that you would not live through the night. Number Eight agreed. How is it that you are not only alive, but unhurt?”

I thought about it for a second before I answered, something I seldom do, then I said, “Perhaps those monks value their own opinions too highly. I can only hope that they have not corrupted anyone else’s thinking.”

“Go sit,” Gaspar said.

Sitting was what we did. To learn to sit, to be still and hear the music of the universe, was why we had come halfway around the world, evidently. To let go of ego, not individuality, but that which distinguishes us from all other beings. “When you sit, sit. When you breathe, breathe. When you eat, eat,” Gaspar would say, meaning that every bit of our being was to be in the moment, completely aware of the now, no past, no future, nothing dividing us from everything that is.

It’s hard for me, a Jew, to stay in the moment. Without the past, where is the guilt? And without the future, where is the dread? And without guilt and dread, who am I?

“See your skin as what connects you to the universe, not what separates you from it,” Gaspar told me, trying to teach me the essence of what enlightenment meant, while admitting that it was not something that could be taught. Method he could teach. Gaspar could sit.

The legend went (I pieced it together from bits dropped by the master and his monks) that Gaspar had built the monastery as a place to sit. Many years ago he had come to China from India, where he had been born a prince, to teach the emperor and his court the true meaning of Buddhism, which had been lost in years of dogma and overinterpretation of scripture.

Upon arriving, the emperor asked Gaspar, “What have I attained for all of my good deeds?”

“Nothing,” said Gaspar.

The emperor was aghast, thinking now that he had been generous to his people all these years for nothing.

He said,

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher