![Life After Death: The Shocking True Story of a Innocent Man on Death Row]()

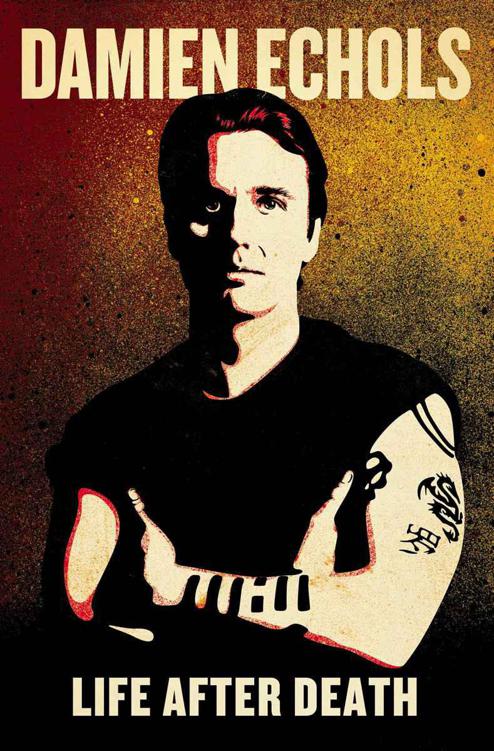

Life After Death: The Shocking True Story of a Innocent Man on Death Row

see that she had the eyes of a young girl. Something about that scared me back then, because I was too young to understand it. I didn’t understand that in those moments she was no longer a grandmother. She was no longer old, no longer the victim of creeping arthritis. She was light and young. She was a stranger to me. She was in another world.

I would sit next to her on the couch as she watched, or quietly lie on the floor. For Christmas she would buy me baseball cards, protective sleeves for them, and albums to store them in. Even though I grew up to be a Boston fan, there’s still a soft spot in my heart for St. Louis. When I watch them play I can still feel my grandmother near me.

Baseball is my escape hatch. When I’m watching it I become enveloped in the feeling that everything will turn out okay. It reminds me that if I just hang on long enough, anything can happen.

One morning in 2006, I called Lorri at our usual time, eight a.m., and she told me that several of the forensic experts had reviewed much of the evidence and come back with the same conclusion: that the vast majority of the wounds on the bodies were made postmortem, and they believed animals were responsible. It was a major development in my favor; however, there had been many of those.

The forensic testing had been facilitated by Peter Jackson and Fran Walsh, who saw

Paradise

Lost

in 2005 and sent money to my defense fund. They also reached out to Lorri, who welcomed their support and their resources with open arms. It was a turning point for me and for Lorri; although it would take several more years and certainly wasn’t guaranteed, Peter and Fran had much to do with my actual release.

* * *

R

umors have continued to mount that animals of a more mundane variety are responsible for most of the damage to the murdered children. It’s beginning to persuade even me, and I am a skeptical sort by nature. If I hadn’t grown so jaded I’d probably be growing excited. These days I don’t hold my breath when waiting on anything, because the nature of the game is false hope. They’ll string you out like a junkie time and time again unless you grow wise to the tricks. I’m not ungrateful, but I’m also not as young as I once was. The hair-trigger reflex of enthusiasm and hope I had when I was young has died a hard death in this lonely land. My eyes won’t light up until the rumors begin to take on the weight of material form.

* * *

T here was some part of me that always knew I would walk out of prison one day. It wasn’t something I knew on an intellectual level, and it went beyond the level people call instinct. It was something I knew not in my head, or even in my heart, but with my soul. I knew it in the same way that I knew the sun would rise and set. It didn’t occur to me to question it, or even think about it. It simply was. Perhaps it was like watching a movie when you know the hero has to win in the end. You expect him to face peril, hardship, and heartache, but you know that in his darkest hour he must still prevail. I knew that the people subjecting me to a living hell were evil, and I couldn’t conceive of a universe that would allow evil to succeed. Don’t get me wrong—I know all too well that horrors and atrocities take place every single day, in every corner of the world. However, those stories were not mine. I grew up on stories, fed on them, lived in them. I grew up knowing that my own life was a story, and the stories I read always had magick in them. Therefore it was ingrained in me, into the deepest levels of my being, to expect there to be magick in my life. I had all the faith in the world that magick would guide me and save me.

I never really had much to do with the technical, legal work in my case. Anytime I even attempted to delve into it, read about it, or understand it, I would feel empty inside. The system was a soulless husk. Coming into contact with it sucked the hope and magick out of me, so I avoided it at all costs. I left the technicalities and legal nit-picking to the attorneys. It wasn’t that I had any faith in them—at least not the early ones—because I did not. Who I had faith in was Lorri.

During the first two years of my incarceration, not one single thing was done by anyone on my behalf. It was Lorri, and Lorri alone, who changed that.

It didn’t happen all at once. As Lorri became a part of my life, she began to educate herself, learning more and more about the legal

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher