![Life After Death: The Shocking True Story of a Innocent Man on Death Row]()

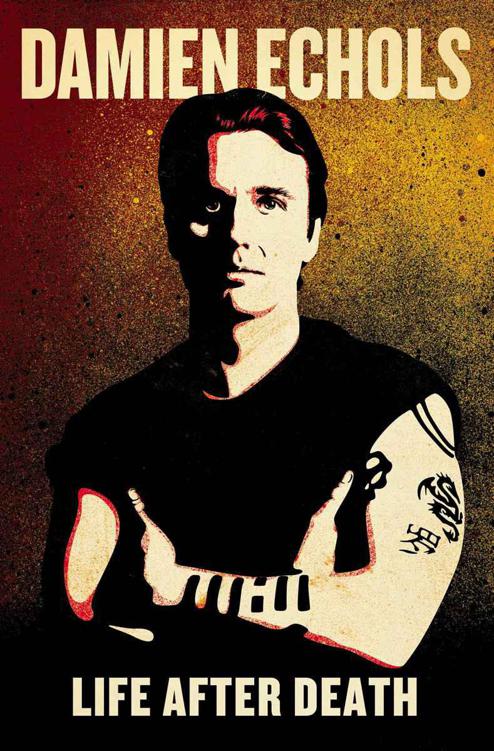

Life After Death: The Shocking True Story of a Innocent Man on Death Row

people’s filth to make you feel clean.

The shack was situated on top of a raised platform of earth in the middle of several miles of field that was used for farming. It was a stereotypical sharecropper’s shanty. Someone probably thought that putting it on the isolated lump of higher ground would keep the rains from washing it away during a flood. That seemed to work, but there were still times when we had to use a fishing boat to reach dry land (the highway, which ran alongside the property) if the nearby swamp overflowed. It turned the only road to town into a small lake so that cars couldn’t get in or out.

We had fourteen large dogs that lived underneath the house. We didn’t mean to have that many originally; they just kept breeding. People who have never known the hunger of being dirt poor always ask why we didn’t have the dogs spayed or neutered. As if the money to do that was just lying around, waiting on us to pick it up. We couldn’t afford a trip to the doctor ourselves, much less for the dogs. More often than not, we had trouble scraping the rent together. The farmer who owned the house didn’t mind if we were a little late with the payment, because he knew we’d eventually come up with it, even if we had to cash in aluminum cans to do so.

Strange things were always hovering at the periphery of my family life, but none so much as during our years in that house. There was just a bad feeling around the place. The house felt malevolent. I could never escape the feeling that the entire place wished me ill. It was the sort of place where, if you lived long enough, a doctor would eventually inform you that your insides were black with cancer and you had only days left to live. It was unpleasant in every regard, and the entire house had the aura of the inside of a body bag. It always felt dark, even on the sunniest summer days. There were odd drawings left on the walls by whoever had lived there before us—things like a grandfather clock with a single eye where the face should have been. They looked like the sorts of things an insane person with a great degree of artistic talent would have created. We painted over most of them, but ran out of paint before we got to the clock. It was worse at night, when you could feel it staring at the back of your head.

That place was never quiet at night. I would lie in bed listening as the dogs dragged strange things to and fro beneath the floor. Inside the house was as dark as an oil slick, so you couldn’t

see

anything moving in the room but you could

sense

it. It was the same sort of sensation you would experience if a closet door were to swing silently open behind your back. Later I learned a term to describe that sensation—air displacement. What I was sensing was air being displaced by something moving from one spot to another. Sometimes late at night I would be overwhelmed with the feeling that someone was standing by the bed, leaning over me, so close they could have brushed their lips across mine if they’d so desired. The breath would pass from its lips to my lips like the taste of something unmentionable. It wasn’t like a ghost or anything; it was just a feeling the house itself radiated, like an aura. My eyes would bulge and strain like an animal’s, fiercely trying to penetrate the darkness.

Eventually we were told to move, and the house was torn down. The suburbs around Marion were expanding, and people who lived in the houses that cost a quarter of a million dollars did not want a tin-roof shack standing on a bone hill in their line of sight. Something like that tends to lower the property values.

Before the shack was torn down, it drew someone else’s attention. All of us used to go to the bank with my stepfather on Friday afternoon to cash his paycheck, especially in the summer. It was the rare few minutes when we could sit inside an air-conditioned building. We probably didn’t smell very nice, because we were sweating twenty-four hours a day. We poured into the bank like a carload of Vikings and tried not to mess anything up.

Every week I would walk around the bank looking at things I’d examined a hundred times before. There wasn’t much else to do. I was taken aback when we walked in one week to see an art display in the lobby. It consisted of a folding wall, almost like a room divider, and it held about twenty paintings. A laminated sheet of paper attached to the display informed the reader that the paintings had been produced

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher