![Lolita]()

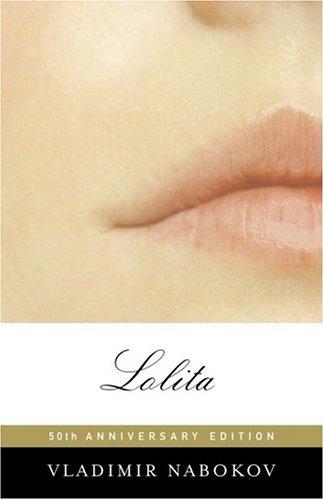

Lolita

I going to thank her—the car had started to move by itself and—Getting no answer, she immersed herself in a study of the map. I got out again and commenced the “ordeal of the orb,” as Charlotte used to say. Perhaps, I was losing my mind.

We continued our grotesque journey. After a forlorn and useless dip, we went up and up. On a steep grade I found myself behind the gigantic truck that had overtaken us. It was now groaning up a winding road and was impossible to pass. Out of its front part a small oblong of smooth silver—the inner wrapping of chewing gum—escaped and flew back into our windshield. It occurred to me that if I were really losing my mind, I might end by murdering somebody. In fact—said high-and-dry Humbert to floundering Humbert—it might be quite clever to prepare things—to transfer the weapon from box to pocket—so as to be ready to take advantage of the spell of insanity when it does come.

20

By permitting Lolita to study acting I had, fond fool, suffered her to cultivate deceit. It now appeared that it had not been merely a matter of learning the answers to such questions as what is the basic conflict in “Hedda Gabler,” or where are the climaxes in “Love Under the Lindens,” or analyze the prevailing mood of “Cherry Orchard”; it was really a matter of learning to betray me. How I deplored now the exercises in sensual simulation that I had so often seen her go through in our Beardsley parlor when I would observe her from some strategic point while she, like a hypnotic subject or a performer in a mystic rite, produced sophisticated versions of infantile make-believe by going through the mimetic actions of hearing a moan in the dark, seeing for the first time a brand new young stepmother, tasting something she hated, such as buttermilk, smelling crushed grass in a lush orchard, or touching mirages of objects with her sly, slender, girl-child hands. Among my papers I still have a mimeographed sheet suggesting:

Tactile drill. Imagine yourself picking up and holding: a pingpong ball, an apple, a sticky date, a new flannel-fluffed tennis ball, a hot potato, an ice cube, a kitten, a puppy, a horseshoe, a feather, a flashlight.

Knead with your fingers the following imaginary things: a piece of bread, india rubber, a friend’s aching temple, a sample of velvet, a rose petal.

You are a blind girl. Palpate the face of: a Greek youth, Cyrano, Santa Claus, a baby, a laughing faun, a sleeping stranger, your father.

But she had been so pretty in the weaving of those delicate spells, in the dreamy performance of her enchantments and duties! On certain adventurous evenings, in Beardsley, I also had her dance for me with the promise of some treat or gift, and although these routine leg-parted leaps of hers were more like those of a football cheerleader than like the languorous and jerky motions of a Parisian

petit rat

, the rhythms of her not quite nubile limbs had given me pleasure. But all that was nothing, absolutely nothing, to the indescribable itch of rapture that her tennis game produced in me—the teasing delirious feeling of teetering on the very brink of unearthly order and splendor.

Despite her advanced age, she was more of a nymphet than ever, with her apricot-colored limbs, in her sub-teen tennis togs! Winged gentlemen! No hereafter is acceptable if it does not produce her as she was then, in that Colorado resort between Snow and Elphinstone, with everything right: the white wide little-boy shorts, the slender waist, the apricot midriff, the white breast-kerchief whose ribbons went up and encircled her neck to end behind in a dangling knot leaving bare her gaspingly young and adorable apricot shoulder blades with that pubescence and those lovely gentle bones, and the smooth, downward-tapering back. Her cap had a white peak. Her racket had cost me a small fortune. Idiot, triple idiot! I could have filmed her! I would have had her now with me, before my eyes, in the projection room of my pain and despair!

She would wait and relax for a bar or two of white-lined time before going into the act of serving, and often bounced the ball once or twice, or pawed the ground a little, always at ease, always rather vague about the score, always cheerful as she so seldom was in the dark life she led at home. Her tennis was the highest point to which I can imagine a young creature bringing the art of make-believe, although I daresay, for her it was the very

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher