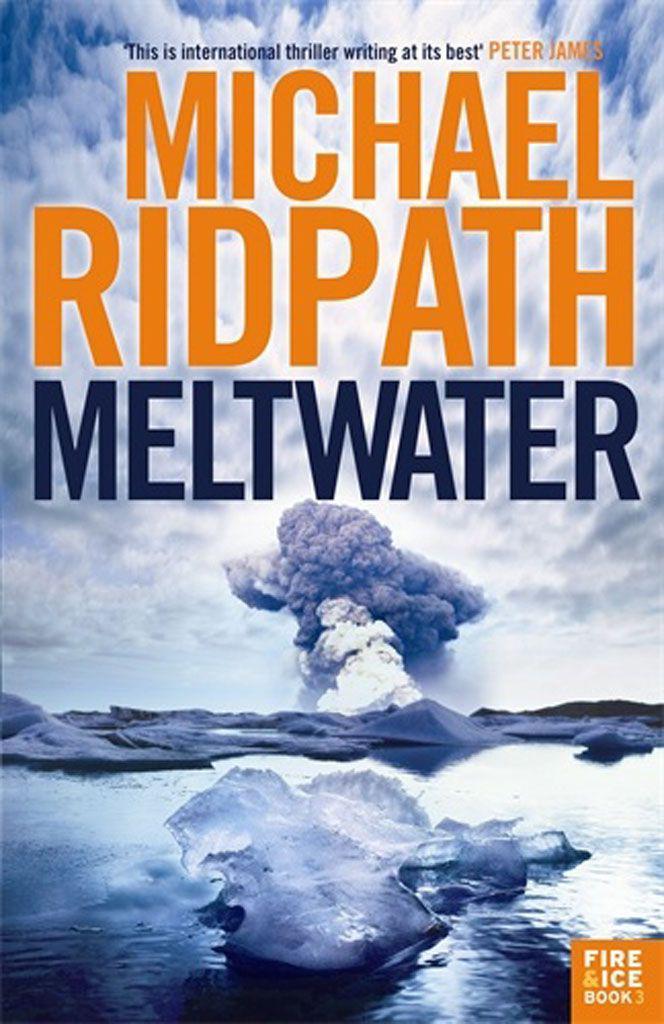

![Meltwater (Fire and Ice)]()

Meltwater (Fire and Ice)

it.’ He grimaced and put his hands over his eyes, fingers splayed open so he could see through them.

Magnus put his foot hard down on the accelerator and the Range Rover surged forward. Magnus had a hunch the faster he went the more likely he would be to avoid falling in if the bridge collapse.

They hit the bridge and in less than ten seconds were over the other side. Mikael Már let out a whoop.

The policeman’s hands had stopped waving and were now raised in a stop sign. Magnus slowed. ‘Sorry about that,’ he said to the face red with anger. ‘Got to get back to

Reykjavík. Give my regards to the chief superintendent.’

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

J ÓHANNES WAS PLAYING hooky and he was loving it. He got up at what for him was a late hour, eight-thirty, and ate a

leisurely breakfast in the hotel dining room, with its wonderful view over Faxaflói Bay. It had been cloudy all night, but a northerly wind seemed to be ushering the bad weather off to the

south. He decided not to call the school. After all, what could they do? Fire him?

There was a flurry of conversation in the dining room about a new eruption on Eyjafjallajökull, 250 kilometres to the southeast, evacuations and possible flooding, but there was nothing in

the morning paper, or at least the edition that had made it to Búdir. He went for a brisk walk along the beach, letting the rhythmic sounds of the waves wash over him, and then got into his

car for the drive to Stykkishólmur. He had rung his old aunt Hildur and agreed to meet her later that morning.

It was a glorious morning. He sang to himself as he drove up over the Kerlingin Pass, crossing the mountain ridge that formed the spine of the Snaefells Peninsula. He was a member of a choir, a

baritone, and a year before they had given a concert of seventeenth-century hymns. They were quite catchy, and Jóhannes had taken to singing them when alone and out of earshot of other

people. ‘Lánid Drottins lítum maeta’, a song about drinking too much wine at the wedding at Cana, was one of his favourites.

That was the glory of the Icelandic countryside. It was very easy to be alone and out of earshot of other people.

He crested the summit of the pass and in a few moments a broad view stretched out before him. He paused, and drove into a lay-by. He walked a few metres away from the car and sat on a stone to

look.

It was a view he remembered well. He had sat close to this very spot with his father when he was about ten. They were driving to see his grandmother in Stykkishólmur, just his father and

him, when they had pulled over. He and his father had already read The Saga of the People of Eyri together at least twice, in the original version of course, and Benedikt wanted to show his

son where it had all happened.

In the foreground was Swine Lake, walled in by the several kilometres of congealed lava which was the Berserkjahraun. Beyond that was Breidafjördur, a long, broad fjord between the

Snaefells Peninsula and the West Fjords, sixty kilometres to the north. Along the coast were two farms. One, nestling under its own fell, with a little black church in the home meadow just beneath

it, was Bjarnarhöfn. This was where Björn the Easterner, the son of Ketill Flat Nose and one of the first settlers of Iceland from Norway, had landed eleven hundred years before. It was

where Vermundur the Lean had brought the two berserkers back from Sweden.

It was also where Hallgrímur had lived. Still lived from what Hermann was saying.

A couple of kilometres to the east was Hraun, now, as it was a millennium ago, a prosperous farm. This was where Vermundur’s brother Styr had lived, whose daughter one of the berserkers

had demanded to marry. Styr had promised the Swede that he could do this as long as the berserkers hacked a path across the lava field to Vermundur’s farm at Bjarnarhöfn. This they did,

collapsing in exhaustion in their master’s brand new stone bath-house afterwards. They were steamed out by Styr, who ran them both through as they emerged. The path was still there, winding

its way through the rearing waves of lava, as was the cairn where the berserkers were buried.

Jóhannes remembered the verse Styr spoke at the cairn:

I dread not my enemy

nor his tyranny.

My bold brave sword

has marked out a place for the berserks.

Hraun was where Benedikt had been brought up.

In fact, throughout the whole plain before Jóhannes, signs of the saga persisted, one thousand years

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher