![Murder at Mansfield Park]()

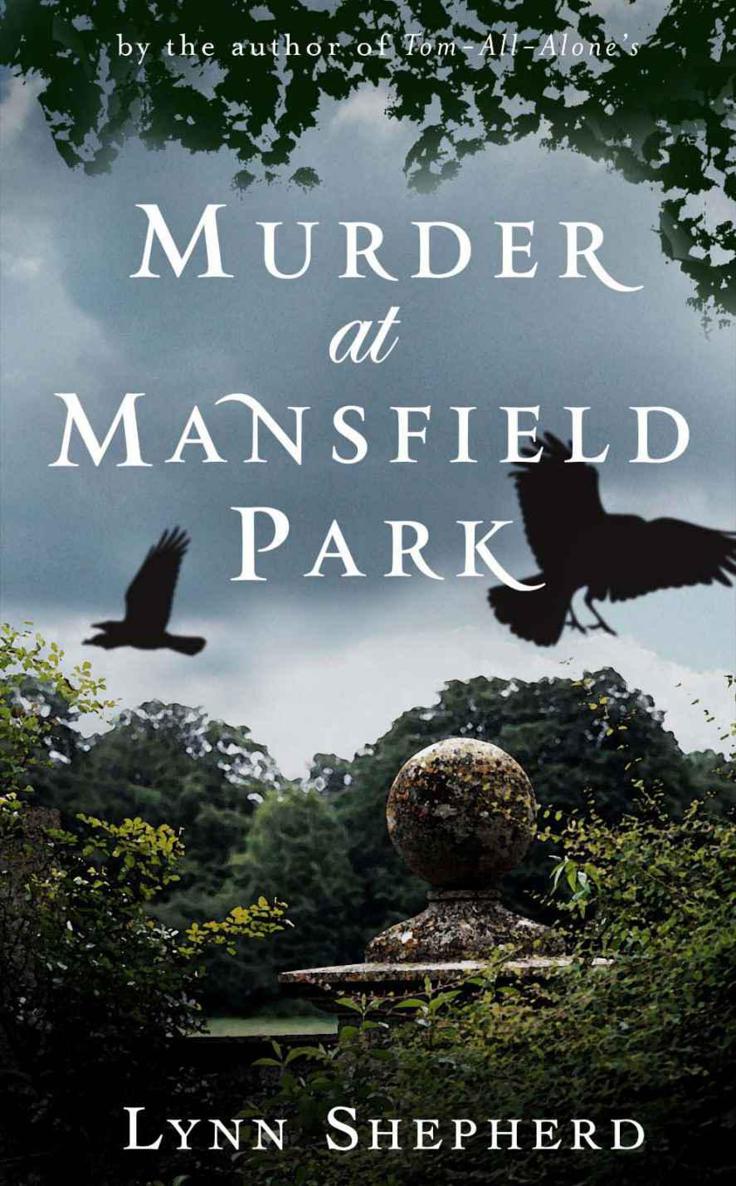

Murder at Mansfield Park

expressed a wish for the relative seclusion of the

supper-room, and she was soon after joined by Henry, who, sitting down next to her with a look of consciousness, said, ‘My own cares are vexing enough, but I am very sorry if any thing has

occurred to distress you . This ought to have been a day of happiness.’

‘Oh! It shall be. It is ,’ said Mary, making an effort for her brother’s sake. ‘Let us say no more about it, I entreat you. I shall have forgotten the whole affair

by morning.’

‘I fear it may prove more enduring than that,’ he replied in a low voice. ‘Just now, when I was with them, I heard Norris asking Miss Price about the necklace.’

‘Mr Norris?’ asked Mary, the colour rushing to her face.

‘The very same. That necklace you are wearing was evidently his gift.’

The truth rushed on Mary in an instant; all of Mr Norris’s unaccountable conduct in the ball-room was now explained; his surprise, his seemingly unintelligible words, and the way he had

looked at her, that was fully accounted for by the extraordinary spectacle of a gift he had presented to one woman being conspicuously displayed around the throat of another.

‘I must find an opportunity to explain,’ she said, in distracted tones, rising from her chair. ‘I must speak to him instantly, I cannot let him think that I—’

‘My dear Mary,’ replied Henry, detaining her, ‘you have not heard the end of my story. When Miss Price gave no immediate answer to his question, Mrs Norris hastened to

explain to him that your necklace is, in fact, an entirely different ornament, of a similar pattern to the one he gave Fanny, but—and here I had difficulty in holding my peace—of inferior workmanship .’

‘But why?’ stammered Mary. ‘What can be the justification for such an unnecessary deception?’

‘Perhaps because Mrs Norris’s beady little eyes have detected some part of the truth? That Miss Price no longer cares for her son—that is, if she ever did—and her making

his gift over to you is proof of that. But, one thing you may be sure of—one thing we may both be sure of,’ this with a look of meaning, ‘is that old Mother Norris will not

let it go as easily as that. That marriage is the favourite project of her heart, and she will do any thing necessary to secure it—even if it means practising deceit on her own

son.’

‘But why should Fanny do such a thing?’ said Mary. ‘She must have known the effect it would produce on Edmund—Mr Norris. I can quite believe that she would connive

most happily at any thing that caused me embarrassment, but what can she hope to gain by behaving so discourteously to Mr Norris? What can be her motive?’

‘I do not pretend to understand Miss Price,’ said Henry grimly, ‘but could it be that she wishes to put his affection to the test? Or to ascertain if he has feelings for

another?’

He stopped. By this time Mary’s cheeks were in such a glow, that curious as he was, he would not press the article farther.

‘I do not like deceiving Mr Norris,’ said Mary after a few moments, oppressed by an anguish of heart.

Henry sighed, and took her hand. ‘But unless you propose to un deceive him, and therefore to contradict Mrs Norris (which would cause no end of vexation, and not least to you, my

dear Mary), then I do not see how it is to be avoided.’

In such spirits as Mary now found herself, the rest of the evening brought her little amusement. She danced every dance, though without any expectation of pleasure, seeing it only as the surest

means of avoiding Edmund. She told herself that he would soon be gone, and hoped that, by the time of his return, many days hence, she would have succeeded in reasoning herself into a stronger

frame of mind. For, although she could see that, contrary to his earlier reserve, he now very much wished to speak to her, she could not yet bear the prospect of listening politely to apologies

that had been extorted from him by falsehood.

CHAPTER VI

The house was very soon afterwards deprived of its master, and the day of Sir Thomas’s departure followed quickly upon the night of the ball. Only the necessity of the

measure in a pecuniary light had resigned Sir Thomas to the painful effort of quitting his family, but the young ladies, at least, were somewhat reconciled to the prospect of his absence by the

arrival of Mr Rushworth, who, riding over to Mansfield on the day of Sir Thomas’s leave-taking to pay

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher