![Niceville]()

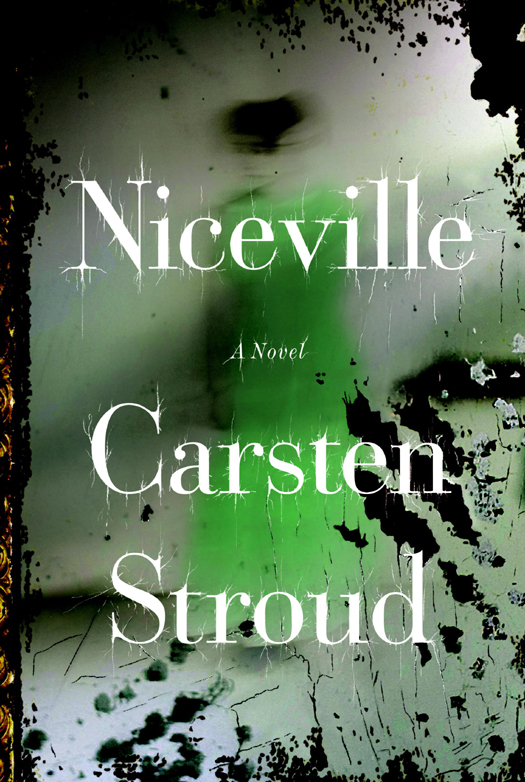

Niceville

disconnect button, then used the number 4 speed-dial key to ring up the registrar’s office at Regiopolis Prep and got Father Casey on the third ring, who confirmed that Rainey had left the school at two minutes after three, part of the usual lemming stampede of chattering boys in their gray slacks and white shirts and blue blazers with the gold-thread crest of Regiopolis on the pockets.

Father Casey picked up on her tone right away and said he’d head out on foot to retrace Rainey’s path along North Gwinnett all the way down to Long Reach Boulevard.

They confirmed each other’s cell numbers and she picked up her car keys and went down the steps and into the double-car garage—her husband, Miles, an investment banker, was still at his office down in Cap City—where she started up her red Porsche Cayenne—red was her favorite color—and backed it down the cobbled drive, her head full of white noise and her chest wrapped in barbed wire.

Halfway along North Gwinnett she spotted Father Casey on foot in the dense crowd of strolling shoppers, a black-suited figure in a clerical collar, over six feet, built like a linebacker, his red face flushed with concern.

She pulled over and rolled down her window and they conferred for about a minute, people slowing to watch them talk, a good-looking young Jesuit in a bit of a lather talking in low and intense tones to a very pretty middle-aged woman in a bright red Cayenne.

At the end of that taut and urgent exchange Father Casey pushed away from the Cayenne and went to check out every alley and park between the school and Garrison Hills, and Sylvia Teague picked up her cell phone, took a deep breath, said a quick prayer to Saint Christopher,and called in the cops, who said they’d send a sergeant immediately and would she please stay right where she was.

So she did, and there she sat, in the leather-scented interior of the Cayenne, and she stared out at the traffic on North Gwinnett, waiting, trying not to think about anything at all, while the town of Niceville swirled around her, a sleepy Southern town where she had lived all of her life.

Regiopolis Prep and this part of North Gwinnett were deep in the dappled shadows of downtown Niceville, an old-fashioned place almost completely shaded by massive live oaks, their heavy branches knit together by dense traceries of power lines. The shops and most of the houses in the town were redbrick and brass in the Craftsman style, set back on shady avenues and wide cobbled streets lined with cast-iron streetlamps. Navy-blue-and-gold-colored streetcars as heavy as tanks rumbled past the Cayenne, their vibration shivering up through the steering wheel in her hands.

She looked out at the soft golden light, hazy with pollen and river mist that seemed always to lie over the town, softening every angle and giving Niceville the look and feel of an older and more graceful time. She told herself that nothing bad could happen in such a pretty place, could it?

In fact, Sylvia had always thought that Niceville would have been one of the loveliest places in the Deep South if it had not been built, God only knew why, in the looming shadow of Tallulah’s Wall, a huge limestone cliff that dominated the northeastern part of the town—she could see it from where she was parked—a barrier wall draped with clinging vines and blue-green moss, a sheer cliff so wide and tall that parts of eastern Niceville stayed under its shadow until well past noon. There was a dense thicket of old-growth trees on top of the cliff, and inside this ancient forest was a large circular sinkhole, full of cold black water, no one knew how deep.

It was called Crater Sink.

Sylvia had once taken Rainey there, a picnic outing, but the spreading oaks and towering pines had seemed to lean in around them, full of whispering and creaking sounds, and the water of Crater Sink was cold and black and still and, through some trick of the light, its surface reflected nothing of the blue sky above it.

In the end they hadn’t stayed long.

And now she was back to thinking about Rainey, and she realized that she had never really stopped thinking about him at all.

The first Niceville cruiser pulled up beside her Cayenne four minutes later, driven by a large redheaded female patrol sergeant named Mavis Crossfire, a seasoned pro in the prime of her career, who, like all good sergeants, radiated humor and cool competence, with an underlying stratum of latent menace.

Mavis

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher