![Niceville]()

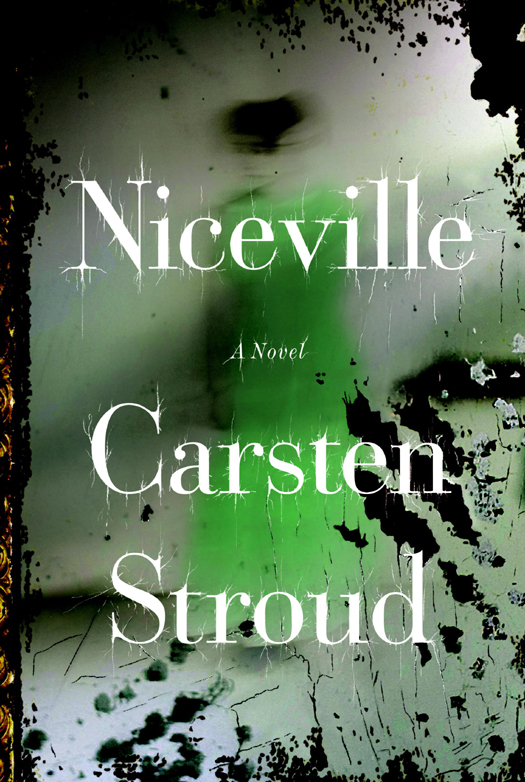

Niceville

big trestle table. There was a woodstove and some kind of icebox from the thirties. There was no formal dining room. A flight of plain wooden stairs rose up into the darkness at the turning of the landing. Music was coming from somewhere, thin and scratchy, some kind of jazzy number with a lot of horns in it. The name of the song floated unbidden into his mind. “Moonlight Serenade,” by Glen Miller.

He had a couple of seconds to take it all in and was looking down at the worn-out floorboards just inside the kitchen door when the wooden slats just sort of rose up at him, at first quite slowly and then a hell of a lot faster. He felt her hands pluck at him, but she wasn’t quick enough. He went down like a man diving off a cliff, hit hard, bounced once, passed out cold, and that was the official end of Merle Zane’s Friday.

Coker’s Shift Ends Dramatically

Coker’s shift ran a lot later than he wanted it to, but all the off-duty guys had come in to help look for the shooters and provide moral support for the survivors, so bailing on all that gung-ho Semper Fi brotherhood-of-the-badge horseshit, and the holy righteous wrath that went with it, would have looked pretty cold-assed.

Around eleven he and a couple of his platoon mates, Jimmy Candles and Mickey Hancock, the shift boss, dropped over to Cedars of Lebanon to see the families of the guys who had gotten killed that day.

This was where the bodies had been taken for the final ME’s report, which was being prepared right now, the forensic autopsies, and all that CSI poodle-fakery.

Coker wasn’t too worried about them finding anything they could use. The only place CSI clues ever solved anything serious was on television.

Even if they figured out the weapon, the good old U.S. of A. was jam-packed with Barrett .50s in civilian hands, thanks to the NRA.

There was Billy Goodhew’s sexy young wife over there, looking weepy, her nose running. Billy Goodhew had been in the county car following right behind the dark blue interceptor, a kind of goofy but brave and highly motivated guy with two tiny girls named Bea and Lillian. Billy had gotten Coker’s second round smack in his kisser. Coker had seen him take it—he liked the kid but it had to be done, and what’re you going to do?

Money for the taking?

Take it.

The world was a mean place and people had to look after their interests, and one of Coker’s interests was in not ever being as dirt-poor and utterly miserable as his alcoholic parents had been.

Taking a long view, for cops, and for combat soldiers, it was Coker’s firm belief that the major glory of the job, and most of the thrill of it, was that you could get killed doing it.

Every now and then somebody actually died on the job. Coker felt that line-of-duty death was like the jalapeños on a chimichanga; it added spice to patrol work that could be pretty damn boring most of the time.

Anyway, there it was: Billy Goodhew was going to his grave without a head and his casket welded shut and Coker and Mickey Hancock and Jimmy Candles, as the senior vets in the platoon, felt they ought to go around and see the families, who were sitting in the lobby of Cedars with about fifty other people, mostly relatives, a few friends.

No newspeople allowed inside.

The newspeople were flitting around out there in the parking lot like a circling cloud of vampire bats, maybe ten or eleven satellite trucks from all the local affiliates and the national cable outfits.

On the way from his patrol car Coker got blocked by a wispy but loudmouthed and universally loathed Cap City news guy named Junior Marvin Felker Junior—known to the cops for reasons lost in time as Mother Felker—who stepped up sprightly and stuck a fat furry mike in Coker’s face and asked him how it felt to have all those dearly beloved cop buddies shot dead in one day.

Coker, always ready to help Mother Felker have a bad day, helped him chew on his fat furry mike for a good long while until Jimmy Candles and Mickey Hancock finally got him to let go. They left Felker lying on his back with blood running from his mouth, screaming something about lawsuits and damages and freedom of the press, in the middle of a glare of lights and mikes, surrounded by all the other hapless media mooks—including his own camera guys—who had done nothing at all to stop what Coker was doing but had somehow managed to get it all on tape.

Inside the hospital it was all white lights and the smell of Lysol and

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher