![Pilgrim's Road]()

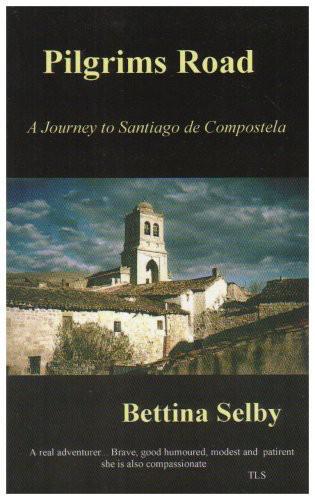

Pilgrim's Road

imagination in regard to the after life in general, and heaven in particular, is C. S. Lewis in his Narnia books. The final one of the series, The Last Battle , tackles many of Christianity’s knottier theological problems, particularly those dealing with death, Judgement and the Hereafter. Because it was written for children, he could not fudge the issues, and while being gripping stuff as all good children’s literature must be, its simplicity is also profound and scholarly, and much admired by many eminent theologians. I particularly love his image of the Resurrection Body’s delight — running and leaping through an idyllic countryside without ever becoming tired. He uses this image to mirror a glimpse into the joys of heaven — a sense of joy, which does indeed echo the Psalms.

If joy is indeed part of the awareness of God, as both the psalmist and C. S. Lewis believed, then this day’s ride was a particularly blessed stage of my journey. The feeling of an all-embracing happiness was so sustained that I began to wonder if some special influence was at work on the Camino hereabouts — Santo Domingo, the builder of the road, perhaps, since his tomb was so close, and since he had been so keen to help pilgrims. A visit to the Bar León , where a special pilgrim log is kept, did nothing to dispel the fancy. Reading through the entries that went back several years, it was clear that I was not the only person to find this an inspirational stretch of the Santiago Road. Many entries were what I would normally describe as way over the top; all about being ‘accompanied by angels’ and the like. I could only read the ones in English, French or Dutch, so what was written in the tongues of less inhibited races I could only imagine. In complete contrast to the more flowery entries, however, was an English one, the work of someone who had clearly not been having a wonderful day. He had also been brooding on the story of the hanged man unhanged ever since leaving Santo Domingo de la Calzada. A blank page of the log had been a spur to his thoughts, which had erupted in an impassioned, blow by blow, account of the miracle. He seemed to have believed in it all implicitly. Yet at the end, missing the point entirely, he had written ‘Bloody Spanish! just the sort of thing some of them would do, hang a pilgrim!’ Xenophobia strikes many travellers from time to time; I could only hope S.G. of Blandford had opportunities to sample the kindness of the Spanish also. His entry was followed by a splendidly succinct one in a child’s round hand. ‘Kes 9 years, a pilgrim’. And if one didn’t fall in love with the human race there and then, after sharing all these outpourings, I decided there could be little hope at all for one in this life.

By noon the day was golden. The wind had sprung up again, but it had swung a hundred and eighty degrees from its usual quarter and was now directly behind me, a rare ‘Sabbath Wind’ which Isbil Roncal had called ‘St James pushing on the pilgrims’. All I had to do for much of the time was to sit up and let the wind do the work — cycle sailing! I was flying over the hills with an ease I thought I had long lost, together with my youth. Had I not had my mind set on nearer sights, I felt as if I could have pushed on and on into the ever-receding blue distance. But I had planned to spend the night at a refugio in an ancient primitive monastery, a little way before Burgos and some distance from the road. Accordingly I exchanged the pleasures of broad smooth tarmac and effortless speed for bumpy narrow country lanes and tracks, and found the sudden quiet and the different smells, sounds and sights an even greater joy. The last few kilometres were on the walkers’ track and this eventually brought me to a clearing in the forests of Montes de Oca where I found the lovely cluster of buildings begun by San Juan de Ortega, the disciple and co-worker of Santo Domingo.

The buildings were in the process of restoration, which is to say that extensive work had been carried out and then abandoned before it was quite finished. Lack of funds accounted for many such attested schemes in Spain, a common problem in countries with an abundant architectural heritage combined with limited funds. Out of sight at the back of the monastery, a dismantled crane, rails, and other building machinery had been left to rust and crumble beneath the long grass of what had once been cloisters. The romantic

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher