![Pow!]()

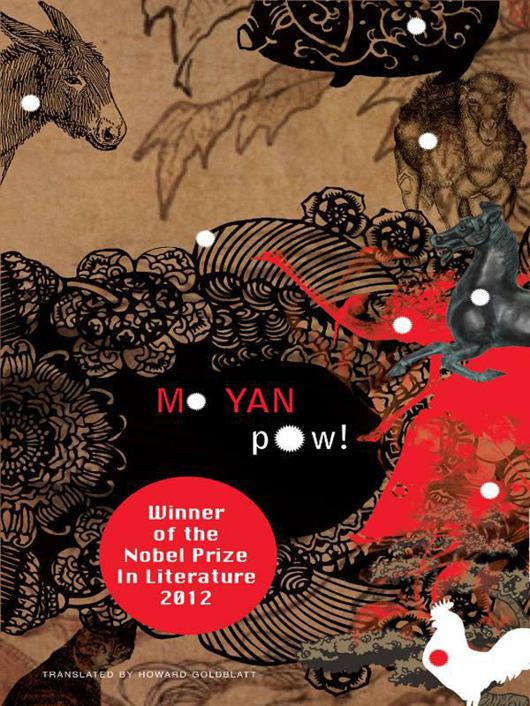

Pow!

that meat, that I was sacrificing myself for Lao Lan and my parents. The sole purpose of the spectacle was to show that we, the residents of Slaughterhouse Village, would never again produce water-injected or otherwise corrupted meat. The fire was the concrete expression of that resolve. Reporters filmed and photographed it from all angles, and the flames attracted a crowd round the plant gate. Including a fellow from a neighbouring village with the unusual name of October. People said he was a mental midget but he didn't seem stupid to me. He elbowed his way up to the fire and stabbed a hunk of meat with a steel pike. Then he ran off, holding the flaming meat over his head, like a torch. Shaped like a large shoe, it dripped grease, tiny, sizzling drops of liquid fire as October shouted excitedly and ran up and down the street. A young reporter snapped his picture, although none of the video cameras turned towards him.

‘Meat for sale,’ he shouted, ‘cooked meat for sale…’

October's performance made him the centre of attention, even as the grand opening ceremony was in progress and the VIP in the middle of his speech. The reporters rushed back with their cameras, though I'd have bet that the younger ones would have preferred to film October's antics. Professional diligence, however, did not allow for impetuous actions.

‘The creation of the United Meatpacking Plant is a historic event…’ The VIP's amplified voice swirled in the air.

October twirled the skewer over his head, like a spear-wielding actor in an opera. The chunk of flaming meat popped and crackled, sending hot drops of grease flying like tiny meteors. A spectator screamed as grease spatter landed on her cheeks. ‘Damn you, October!’ she cursed.

People ignored her, preferring to watch October and reward him with the odd encouraging shout of ‘Bravo, October, bravo!’ People in the crowd jumped out of the way with a skill and a vigour to match his.

‘In line with our goal to supply the masses with worry-free meat, we have created the Huachang brand and ensure its reputation…’ Lao Lan was speaking now.

I took my eyes off October, just for a moment, to see if I could find my father. In my mind, the plant manager ought to be on the speaker's platform at this important moment, and I fervently hoped he wasn't still hanging round the fire. I was in for another disappointment, for that's exactly where he was. The attention of most of the people there had been drawn by October, all but a few old-timers hunkered down alongside the drainage ditch and close to the fire, probably trying to keep warm. Two people were standing: one was my father, the other a uniformed man who worked for Lao Han and who was poking the flaming pile with a steel pole as if it were a sacred duty. My father's unblinking eyes were fixed on the flames and the smoke as he stood almost reverently, his suit curling from the heat. From where I stood he looked like a charred lotus leaf that would crumble at the slightest touch.

All of a sudden I felt very afraid. Was there something wrong with his mind? I was suddenly afraid that he'd throw himself onto the pyre and join that meat in its martyrdom. So I grabbed Jiaojiao's hand and ran towards the burning pile as shouts of alarm erupted behind us, followed by uproarious laughter. Instinctively, we turned to see what had happened. Apparently the meat on October's pike had flown off like a leaping flame and landed on top of a parked luxury sedan. The driver shrieked in alarm, he cursed, he jumped, he tried desperately to knock the flaming meat off his car but carefully for fear of being burnt. He knew the car could go up in flames, perhaps even explode. Suddenly he took off one of his shoes and knocked the meat to the ground.

‘We are committed to putting in place a system of checks that will enable us to carry out our sacred duty, ensuring that not a single piece of nonstandard meat ever leaves this plant…’ The passionate voice of Lao Han, chief of the Inspection Station, momentarily drowned out the noises on the street.

Jiaojiao and I reached Father, then we pushed and shoved and pinched him until he reluctantly took his eyes of the pyre and gazed down at us. In a hoarse, raspy voice—as if the flames had seared his larynx—he asked: ‘What are you children doing?’

‘Dieh,’ I said, ‘you shouldn't be standing here.’

‘Where do you think I should to be standing?’ he asked, a bitter smile

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher