![Pow!]()

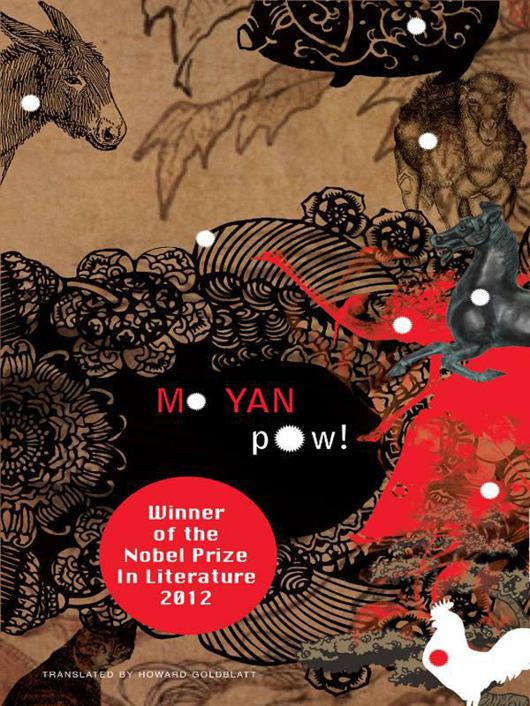

Pow!

be the moment when my heart would swell with pride and I'd vow that this was how I'd do things, that this was the kind of man I wanted to be. It was obvious to the peddlers as well that something was in the air that day, and they turned to look at my father, except for a few who coolly observed the butchers as they paced. A tacit agreement had been reached: they would all wait to see what happened, like an audience patiently waiting for the play to begin.

POW! 7

Outside, the rain has let up a little, the thunder and lightning have moved away. In the yard, the stone path is submerged under a layer of water on which float leaves—some green, some brown. There is also a plastic blow-up toy, its legs pointing skyward. It appears to be a toy horse. Before long the rain stops altogether, and a breeze arrives from the fields, rustling the leaves of the gingko tree and sending down a fine silver spray, as if through a sieve, poking holes in the water below. The two cats stick their heads out of the hole in the tree trunk, screech briefly and pull their heads back in. I hear the pitiful mewling of kittens somewhere in that hole and I know that, while the sky was opening up, sending torrents of water earthward, the tailless female has had her litter. Animals prefer to give birth during downpours, so my father says. I see a black snake with a white pattern slithering through the water. Then there's a silvery fish that leaps into the air, twisting its flat body like a plough blade, beautiful yet powerful, graceful and smooth, making a moist, crisp noise as it re-enters the water, like the slap Butcher Zhang gave me, his hand slippery from pig grease, when he caught me sneaking a piece of meat. Where has that fish come from? It alone knows the answer. It can barely swim in the shallow water, its green dorsal fin exposed to the air. A bat emerges from the temple and flies past, followed by a swarm of bats, all from the same place. The other two hailstones that landed at my feet have melted before I could suck on them. Wise Monk, I say, it'll be dark soon. No response.

A bright red sun rose above the fields in the east, looking like a blacksmith's glowing face. The leading actor of the play finally appeared in the square: our village head, Lao Lan, a tall, husky man with well-developed muscles (that was before he got fat, before his belly bulged, before his jowls sagged). He had a bushy brown beard, the same colour as his eyes, which made you wonder if he was of pure Han stock. All eyes were on him the minute he strode into the square, his face glowing in the sun. He walked up to my father but his gaze was fixed on the fields beyond the squat earthen wall, where rays of morning sun dazzled the eye. The crops were jade green, the flowers were in bloom, their scent heavy on the air, the skylarks sang in the rosy red sky. My father, who was nothing in the eyes of Lao Lan, might as well not have been sitting by the wall at all. And if my father meant nothing to him, naturally, it was even worse for me. But perhaps he was blinded by the sun. That was the first thought that entered my juvenile mind, but I quickly grasped that Lao Lan was trying to provoke my father. As he cocked his head to speak to the butchers and the peddlers, he unzipped his uniform pants, took out his dark tool and let loose a stream of burnt-yellow piss right in front of my father and me. Its heated stench assailed my nostrils. It was a mighty stream, I'd say a good fifteen metres; he'd probably been saving up all night, going without relieving himself so he could humiliate my father. The cigarettes on the ground tumbled and rolled in his urine, swelling up until they lost their shape. A strange laugh had arisen from the clusters of butchers and peddlers when Lao Lan took out his tool, but they broke that off as abruptly as if a gigantic hand had reached out and grabbed them by the throats. They stared at us, slack-jawed and tongue-tied, their faces frozen in stunned surprise. Not even the butchers, who knew that Lao Lan wanted to pick a fight with my father, imagined that he'd do something like this. His piss splashed on our feet and on our legs, some even spraying into our faces and our mouths. I jumped up, enraged, but Father didn't move a muscle. He sat there like a stone. ‘Fuck your old lady, Lao Lan!’ I cursed. My father didn't make a sound. Lao Lan wore a superior smile. My father's eyes were hooded, like a farmer taking pleasure from the sight of

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher