![Pow!]()

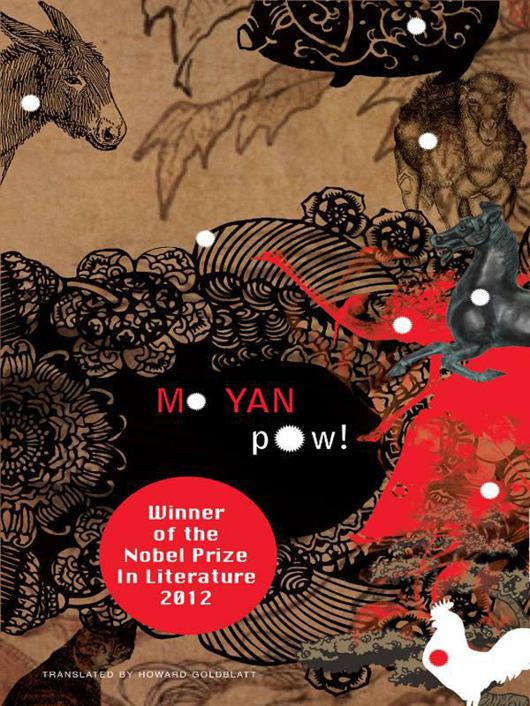

Pow!

and a chorus of turbulent and chaotic drumbeats, gong clangs, music strains and marchers’ shouts fill the air. A dozen TV journalists jockey for position to film the scene. One of them, wanting to get a special shot, has come too close to a camel; it angrily bares its teeth, then roars and spits a gooey missile at the man, temporarily blinding both him and his camera. He screams as he jumps out of the way, drops his camera, bends over and wipes his eyes with his sleeve, as a man responsible for the arrangement of the parade participants raises his flag and shouts at everyone to take their places on the Festival grounds. The cow-headed and chicken-headed floats make slow turns onto the grassy field, followed by a seemingly unending body of parade contingents. The acrobat, with his martial bearing, steps nimbly and smiles broadly as he leads the East City camel unit onto the grass. The abused journalist standing by the side of the road assails his tormentor with loud curses but is totally ignored. The camels are more or less orderly as they move forward, but the twenty-four ostriches seem angry about something, and their formation breaks down as they run helter-skelter towards the temple grounds, drawing terrified shrieks from their riders, some of whom slide quickly out of the saddle, while others cling to the necks of their mounts, their young faces drenched with sweat. Once the ostriches reach our yard they huddle together, shuffling back and forth. That's when I discover that the birds’ feathers, which looked so dull from a distance, are actually quite beautiful in the sunlight. It's a simple beauty, like priceless Qin Dynasty brocade. Some employees of the Rare Animals Slaughterhouse Corporation frantically try to herd the ostriches back, but all they manage to do is scare them further. I look into the ostriches’ hate-filled little eyes, listen to their hoarse screeches and watch as one of them kicks a worker in the knee. Knocked to the ground, he grabs his injured knee and utters a cry of pain, his face waxen and his forehead beaded with sweat. The ostriches take off running, the hard knuckles of their feet pounding loudly on the ground. I know that those feet can kick as hard as a horse, and I've been told that a mature bird isn't afraid to take on a lion. An ostrich's toes are hardened from a lifetime of running across the savanna, so it's a foregone conclusion that the man sitting on the ground yelping in pain has a badly injured knee. When a couple of his friends lift him up by the arms, he immediately sits back down. By now, most of the children have slid off their mounts, all but one girl and one boy who hold on tenaciously. Rivulets of sweat smear the paint on their taut faces until they look like artists’ palettes. The boy is clutching the joint connecting the ostrich's wings to its body as he bounces up and down with every step the bird takes. He holds on to the wings even when his rear end is up in the air; but then the ostrich makes a mad dash and he slips sideways under the mouth-gaping, eye-popping stares of the people round him, none of whom makes a move to come to his rescue. A moment later, he's lying on the ground clutching two fists full of feathers, until someone walks over and picks him up. He bites his lip as the tear dam bursts. Meanwhile, the riderless ostrich has rejoined the herd and is breathing heavily and noisily through its open mouth. The girl still has her arms wrapped round the neck of her bird, though it is trying its best to dislodge her. But she's too much for it, thanks to a panic attack and, in the end, she gets it to slump to the ground, neck and head lying in the dirt, tail end pointing skyward, flinging mud behind it as it paws the ground in vain.

All that pork lay heavily in my stomach, churning and grinding like a litter of soon-to-be-born piglets. But of course I was no sow, so I couldn't possibly know what that felt like. The belly of the pregnant sow at Yao Qi's nearly scraped the ground when she grunted her way over to the snow-covered garbage heap in front of the newly opened Beauty Hair Salon, to root out edible titbits. Lazy, fat and carefree, she was, as anyone could see, a happy sow, in a different class from the two skinny-as-jackals, moody, human-hating little pigs we'd once raised. Yao Qi made sausage out of meat so fatty that even the dogs turned their noses up at it, filled with sweet potato starch and red-dyed bean-curd skin, to which he added

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher