![Pow!]()

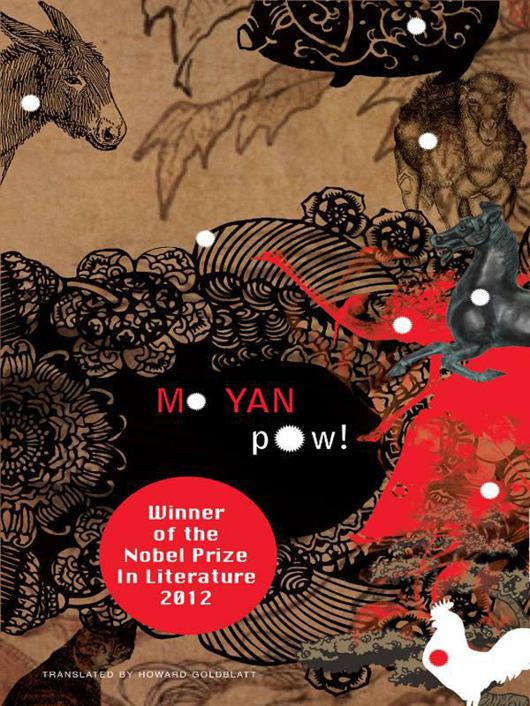

Pow!

You can tell him if you want. Tell him Yao Qi is going to take up the fight against him. I'm not afraid.’

‘I wouldn't do anything as low-down as that,’ Father said.

‘Who knows,’ Yao Qi sneered. ‘It looks to me like you left your balls up in the northeast, my friend.’ Looking down at Father's pants he asked, ‘Does that thing still work?’

POW! 25

Late night. The four carriers lean against the ginkgo tree, chins on their chests, snoring loudly. The lonely female cat emerges from her hole in the tree and transfers the labourer's uneaten meat from the flatbed truck to her home, over and over until it's all safely tucked away. A white mist rises from the ground, blurring and adding a sense of mystery to the red lights of the night market. Three men with burlap sacks, long-handled nets and hammers, skulk out of the darkness, reeking of garlic. A roadside tungsten lamp that has just been turned on is bright enough for me to see their shifty, cowardly eyes. ‘Wise Monk, hurry, the cat-nappers are here !’ He ignores me. I've heard that some of the restaurants have created a special Carnivore Festival dish with cat as its main ingredient to satisfy the refined palates of tourists from the south. Back when I was roaming the city streets at night I spent some time with cat-napper gangs, so as soon as I saw the tools of their trade I knew what they'd come for. I'm embarrassed to admit, Wise Monk, that when I was hard up in the city I threw in my lot with them. I know that city folk spoil their cats worse than their sons and daughters. Unlike ordinary tomcats, these cats seldom leave their comfy confines, except when they're in heat or ready to mate, and then they prowl the streets and alleyways looking for a good time. People in love take leave of reason, and cats in love make tragic mistakes. Back then, Wise Monk, I fell in with three fellows and went out with them at night to lie in wait where the cats tended to congregate. Under cover of hair-raising screeches and caterwauls, we sneaked up on stupid, fat-as-pigs, pampered felines that shuddered at the sight of a mouse as they rubbed up against one another, and the second they coupled they were snagged by the fellow with the net. Then, while the trapped cats struggled, the fellow with the hammer ran up. A few well-placed thwacks and presto ! we had two dead cats. The third fellow picked them out and deposited them in the sack I held. We'd slink off then, hugging the walls, heading for the next cat hangout. Our best haul was two bags full, which we sold to a restaurant for four hundred yuan. Since I wasn't a proper member of the team, more the odd-man-out, they only gave me fifty yuan. I blew it on a meal at a restaurant. I went out a second time, but there wasn't a trace of cats at the underground passageway. Since I knew I'd never find them during the day, I waited till nightfall. But the minute I arrived I was arrested by the metropolitan police. Without as much as a ‘how do you do’ they began to give me the full treatment. I denied I was a cat-napper, but one of them pointed to the blood on my shirt, called me a liar and began all over again. Then they took me to a place where there were dozens of owners of lost cats: white-haired old men and women, richly jewelled housewives and teary-eyed children. As soon as they heard who I was, they pounced on me, hurling tearful accusations and beating me in rage. The men kicked me in the shins and in the balls, the most painful spots, oh, Mother, how it hurt ! The women and the girls were worse—they pinched my ears, gouged my eyes and twisted my nose. An old woman with shaking hands elbowed her way up to me and scratched my face. Not entirely satisfied, she then took a bite out of my scalp. Somewhere along the way I fainted. When I woke up I found myself buried under a pile of garbage. I clawed my way out frantically, stuck my head into the open air and took some deep breaths. And there I was, sitting on a pile of garbage, looking down on the bustling city streets in the distance, sore, hungry and feeling like I was at death's door. That's when I thought about my mother and my father, about my sister, even about Lao Lan, thought about how I'd been free to eat all the meat I wanted when I was a slaughterhouse workshop director, about when I could drink as much liquor as I wanted, about when everyone respected me, and the tears fell like pearls from a broken string. I was spent, resigned to dying on top

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher