![Praying for Sleep]()

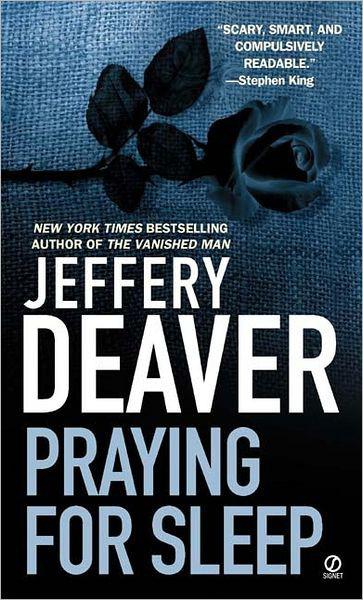

Praying for Sleep

Richard Kohler had learned not to take personal offense at anything schizophrenic patients said or did. If Ronnie’s words troubled him at all, it was only because they offered a measure of the patient’s relapse.

This was one of Kohler’s clinical errors. The patient, involuntarily committed at Marsden State hospital, had responded well to his treatment there. After many trials to find a suitable medication and dosage Kohler began treating him with psychotherapy. He made excellent progress. When one of the halfway-house patients had improved enough to move into an apartment of her own, Kohler placed Ronnie here. Immediately, though, the stresses accompanying communal living had brought out the worst of Ronnie’s illness and he’d regressed, growing sullen and defensive and paranoid.

“I don’t trust you,” Ronnie barked. “It’s pretty fucking clear what’s going on here and I don’t like it one bit. And there’s going to be a storm tonight. Electric storm; electric can opener. Get it? I mean, you tell me I can do this, I can do that. Well, it’s bullshit!”

Into his perfect memory Kohler inserted a brief mental notation about Ronnie’s use of the verb “can” and the source of his panic attack tonight. It was too late in the evening to do anything with this observation now but he’d review the young man’s file tomorrow in his office at Marsden and write up a report then. He stretched and heard a deep bone pop. “Would you like to go back to the hospital, Ronnie?” he asked, though the doctor had already made this decision.

“That’s what I’m getting at. There isn’t that racket there.”

“No, it’s quieter.”

“I think I’d like to go back, Doctor. I have to go back,” Ronnie said as if he were losing the argument. “There are reasons too numerous to list.”

“We’ll do it then. Tuesday. You get some sleep now.”

Ronnie, still dressed, curled up on his side. Kohler insisted that he put on his pajamas and climb under the blankets properly, which he did without comment. He ordered Kohler to leave the light on, and did not say good night when the doctor left his room.

Kohler walked through the ground floor of the house, saying good night to the patients who were still awake and chatting with the night orderly who sat in the living room, watching television.

A breeze came through the open window and, enticed by it, Kohler stepped outside. The night was oddly warm for November. It reminded him of a particular fall evening during his last year of medical school at Duke. He recalled walking along the tarmac from the stairs of the United 737. That year the trip between La Guardia and Raleigh-Durham airports had been like a commute for him; he’d logged tens of thousands of miles between the two cities. The night he was thinking of was his return from New York after Thanksgiving vacation. He’d spent most of the holiday itself at Murray Hill Psychiatric Hospital in Manhattan and the Friday after it in his father’s office, listening to the old man argue persuasively, then insist belligerently, that his son take up internal medicine—going so far as to condition his continuing financial support of the young man’s education on his choice of specialty.

The next day, young Richard Kohler thanked his father for his hospitality, took an evening flight back to college and when school resumed on Monday was in the Bursar’s Office at 9:00 a.m., applying for a student loan to allow him to continue his study of psychiatry.

Kohler again yawned painfully, picturing his home—a condominium a half hour from here. This was a rural area, where he could have afforded a very big house and plenty of property. But Kohler’s goal had been to forsake land for convenience. No lawn mowing or landscaping or painting for him. He wanted a place to which he might escape, small and contained. Two bedrooms, two baths and a deck. Not that it didn’t have elements of opulence—the condo contained one of the few cedar hot tubs in this part of the state, several Kostabi and Hockney canvases and what was described as a “designer” kitchen (“But aren’t all kitchens,” he had slyly asked the real-estate broker, “designed by somebody? ” and enjoyed her sycophantic laughter). The condo, which was on a hilltop and looked out over miles and miles of patchwork woods and farm-land during the day and the sparkling lights of Boyleston at night, was—quite literally—Kohler’s island of sanity

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher