![Praying for Sleep]()

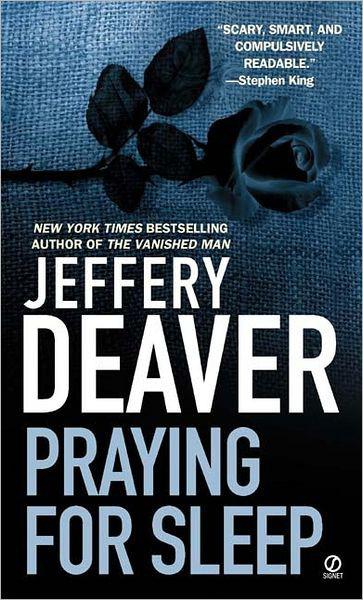

Praying for Sleep

last year in the company of another woman.

He’d met her at a legal continuing-education conference. She was a trust-and-estates lawyer, thirty-seven years old, divorced with two children. He offered these facts as proof of the virtue of his infidelity; no young, gum-snapping bimbo for him.

Yale-educated.

Cum laude.

“Do you think I give a fuck about her credentials?” Lis had shouted.

When she’d first seen a MasterCard receipt for a hotel in Atlantic City, dated the weekend he was supposed to be in Ohio on business, she was devastated. Never before a victim of adultery, Lis hadn’t realized that illicit sex is only a part of the infidelity game. There’s illicit affection too, and she wasn’t sure which hurt the worst.

Why, bedding the bitch in Trump’s Palace, her highly educated thighs squeezing Owen’s, flicking tongues, shared spit, exposed nipples and cock and cleft . . . Those were bad enough. But Lis was almost more stung by the thought of their joined palms, romantic walks on the turbulent Jersey beach, the two of them sitting on a bench and Owen sharing his most private thoughts.

Stern Owen! Her quiet Owen.

Owen from whose mouth she had to pry words.

Much of this was speculation of course (he’d learned his lesson and volunteered nothing more after blurting out the woman’s CV). But the thought alone of an intimacy deeper than sex was horrifying to Lis and her fury at their furtive conversations and entwined fingers grew beyond all reasonable proportion. For weeks after his confession she was racked by a sensation that she might at any moment erupt in madness—anytime, anywhere.

By the time she confronted him, the affair was over, he said. He’d taken his wife’s head in his long hands, stroking her hair, jiggling the earrings he’d given her (during the height of his infidelity, Lis had noted with ire, and that night pitched the jewelry out). The woman had asked him to leave Lis, Owen said, and marry her. He refused, they fought and the affair ended bitterly.

After the initial, cataclysmic weeks following this confession, after the long nights of silence, after those funereal Sunday mornings, after an intolerable Thanksgiving, they began to discuss the matter as couples do—tactically, then obliquely, then reasonably. Lis now had only vague memories of the conversations. You’re too demanding. You’re too strict. You’re too quiet. You’re too reclusive. You’re not interested in what I do. You have to loosen up sexually. You come on like a rapist. You never complained. . . . Yes but you scare me sometimes I can’t tell what you’re thinking yes but you’re so stubborn yes but . . .

The second-person pronoun occurs never so often as in the aftermath of infidelity.

Finally they decided to consider divorce and went their separate ways for a time. During this period Lis finally admitted to herself that the affair was no surprise. Not really. Owen’s having an attorney for a lover, well, that was a shock, yes. He didn’t fare well with strong women. To hear him tell it, his best relationship prior to Lis had been with a young Vietnamese woman in Saigon during the war. He was tactfully reluctant to go into many details but he described her glowingly as sensitive and demure. It took Lis some translating, and prying, to figure out that this meant she was subservient and complacent and she spoke very little English.

That’s a relationship? she wondered, unnerved to find that this was the sort of woman her husband had sought out. Still, there seemed to be something more to the liaison. Something dark. Owen wouldn’t go into the details and Lis was left to speculate. Maybe he had accidentally wounded her and stayed with her out of loyalty, slipping her stolen rations and medicines and nursing her to health. Maybe her father was a Viet Cong whom Owen had killed. Plagued with guilt, he’d offered some reparation and fallen in love.

This all seemed far too romantic, operatic even, for Owen Atcheson, and she ultimately attributed the affair to youthful lust, and his fond memories of it to the revisionist ego of a middle-aged man. But there was no denying that a servile young thing had a certain appeal to him. The greatest friction between them—and his worst flares of temper—arose when she opposed him. She could rattle off a hundred examples—buying the nursery, urging him to be more of a sexual partner, suggesting they see a therapist when the marriage hit rough spots,

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher