![Praying for Sleep]()

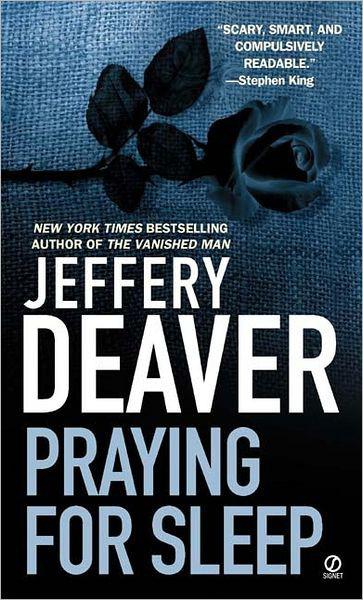

Praying for Sleep

you get off that damn bike?” Heck muttered. “Can’t you hoof it? Like a normal escapee?”

Emil slowed and looked around him. A bad sign. I got you for your nose, boy, not your eyes. Hell, I can see better’n you.

The hound slowly strolled off the road and into a field. His leg on fire, Heck led the dog along a grid search pattern, loping in huge squares over the ground, moving slowly under the guidance of the flashlight for fear of the steel traps. Emil paused for long moments, sniffing the ground then lifting his nose. Then he ambled off and repeated the process. As Heck watched the hound his sense of futility grew.

Then Heck felt a tug on the track line and he looked down with hope in his heart. But immediately the line went slack, as Emil gave up on the false lead and returned to nosing about in the ground, breathing in all the aromas of the countryside and searching in vain for a scent that, for all Heck knew, might have vanished forever.

Michael Hrubek’s father was a grayish, somber man who had, over the years, grown dazed by the disintegration of his family. Rather than avoiding home, however, as another man might have done, he dutifully returned every evening from the clothing store in which he was the formal-wear manager.

And he returned quickly—as if afraid that in his absence some new pestilence might be threatening to destroy whatever normalcy remained in his house.

Once home though he spent the tedious hours before bed largely ignoring the chaos around him. For diversion he took to reading psychology books for laypeople and excerpts from The Book of Common Prayer and—when neither proved to be much of a palliative—watching television, specifically travel and talk shows.

Michael was then in his midtwenties and had largely given up his hopes of returning to college. He spent most of his time at home with his parents. Hrubek senior, attempting to keep his son happy and, more to the point, out of everyone’s hair, would bring Michael comic books, games, Revell models of Civil War weaponry. His son invariably received these gifts with suspicion. He’d cart them to the upstairs bathroom, subject them to a pro forma dunking to short out sensors and microphones then stow the dripping boxes in his closet.

“Michael, look: Candyland. How ’bout a game later, son? After supper?”

“Candyland? Candyland? Do you know anybody who plays Candyland? Have you ever met a single person in the fucking world who plays Candyland? I’m going upstairs and taking a bath.”

For his part, Michael avoided his father as he avoided everyone else. His rare forays outside the house were motivated by pathetic missions. He once spent a month looking for a rabbi who would convert him to Judaism and he devoted three fervent weeks to hounding an anxious Armed Forces recruitment officer, who couldn’t shake the young man even after explaining a dozen times that there was no longer a Union Army. He took a commuter train to Philadelphia, where he stalked an attractive black newscaster and once cornered her on the street, demanding to know if she was a slave and if she enjoyed pornographic films. She got a restraining order that the police seemed eager to enforce with whatever vigor was necessary but Michael soon forgot about her.

On Saturday mornings his father would make a big pancake breakfast and the family would eat amid such ranting from Michael that his parents eventually tuned out the noise. Michael’s mother, most likely still in her nightgown, would pick at her food until she could face the plate no longer. She would rise slowly, put on lipstick, because that’s what proper ladies did after meals, and after spending several frantic minutes looking for the TV Guide or the remote control, she would return to bed and click on the set. His father did the dishes then took Michael to a doctor whose small office was above an ice-cream parlor on Main Street. All that Michael remembered about this man was that with almost every sentence he said, “Michael.”

“Michael, what I’d like to do today is for you to tell me what some of your earliest memories are. Can you do that, Michael? An example would be: Christmas with your family. Christmas morning, Michael, the very first time—”

“I don’t know, fucker. I can’t remember, fucker. I don’t know anything about Christmas, fucker, so why do you keep asking me?”

Michael said “fucker” even more often than the doctor said “Michael.”

He

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher